At a webinar I attended yesterday, one of the speakers worked for Indian Country Today. He spoke a bit about climate and pointed out that Native people have been adapting to changing climate for 10,000 years. Recently in the scientific literature, we’ve heard much more about traditional burning practices, and what we can learn from Native American practices. Perhaps the selection of Deb Haaland as Interior Secretary could accelerate this trend, especially with scientific research as USGS is in Interior.

Thanks to Rebecca Watson for the link to this interesting (open-source, yay!) study by Roos et al.

Policy Implications.

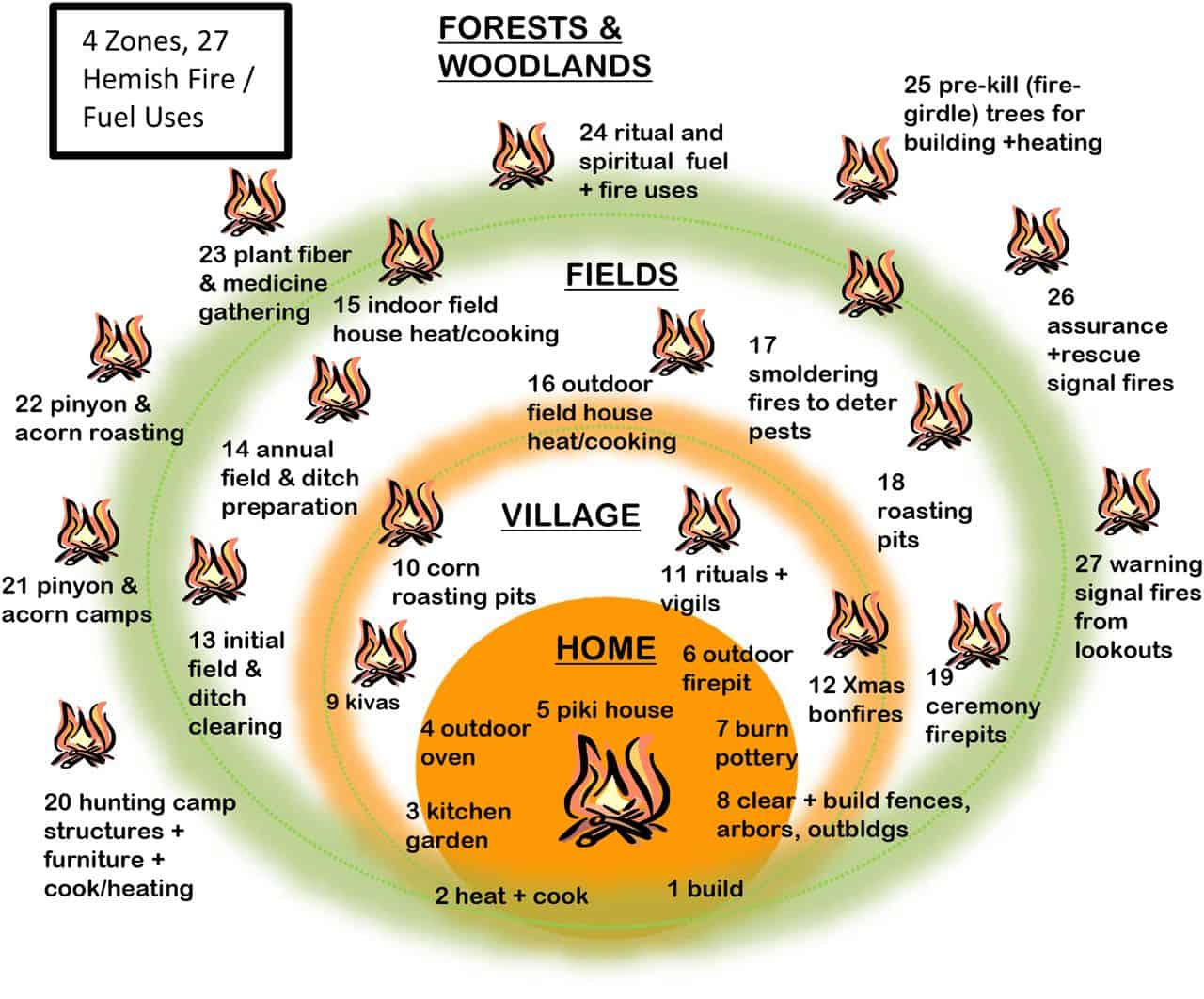

The Jemez ancient WUI obviously contrasts with modern WUI in the American West in ways that make the ancient WUI an imperfect analog for modern conditions. The economic, technological, and political differences are irreconcilable but they do not obviate the relevance of the ancient WUI for modern problems. The cultural contrasts between ancient and modern WUI highlight opportunities to cultivate more resilient communities by supporting particular cultural values. Two of the important characteristics of the Jemez ancient WUI are: 1) That it was a working landscape, in which properties of the fire regime were shaped by wood, land, and fire use that supported the livelihoods of the residents; and 2) that there was much greater acceptance of the positive benefits of fire and smoke. We emphasize that these are malleable cultural features, because reshaping western United States culture by learning from indigenous cultural values may be critical for building adaptive and transformative resilience in modern communities (26, 28, 85, 86). Learning to value the positive benefits of fire and smoke and to tolerate their presence will undoubtedly be critical to WUI fire adaptations. Furthermore, the ancient WUI highlights two key processes that may make modern WUI more resistant to extreme fires: 1) Intensive wood collecting and thinning, particularly in close proximity to settlements; and 2) using many small, patchy fires annually (approximately 100 ha) rather than using larger burn patches (thousands of hectares) to restore fire and reduce fuel hazards, particularly closer to settlements. Many WUI communities—especially rural and Indigenous communities—rely on domestic biomass burning for heat during the winter. Public/private–tribal partnerships to thin small diameter trees and collect downed and dead fuel for domestic use could have dual benefits for the community by meeting energy needs and reducing fuel loads. Tribal communities that have deep histories in a particular forested landscape may be ideal partners for supervising such a program (87). Lessons from the Jemez ancient WUI also suggest that federal and state programs to support prescribed burning by Native American tribes, WUI municipalities, and private land owners would provide equal benefit to modern communities (88). It is imperative that we understand the properties and dynamics of past human–natural systems that offer lessons for contemporary communities (89⇓–91). The Jemez ancient WUI is one of many such settings (72, 92⇓⇓⇓⇓–97) where centuries of sustainable human–fire interaction offer tangible lessons for adapting to wildfire for contemporary communities.