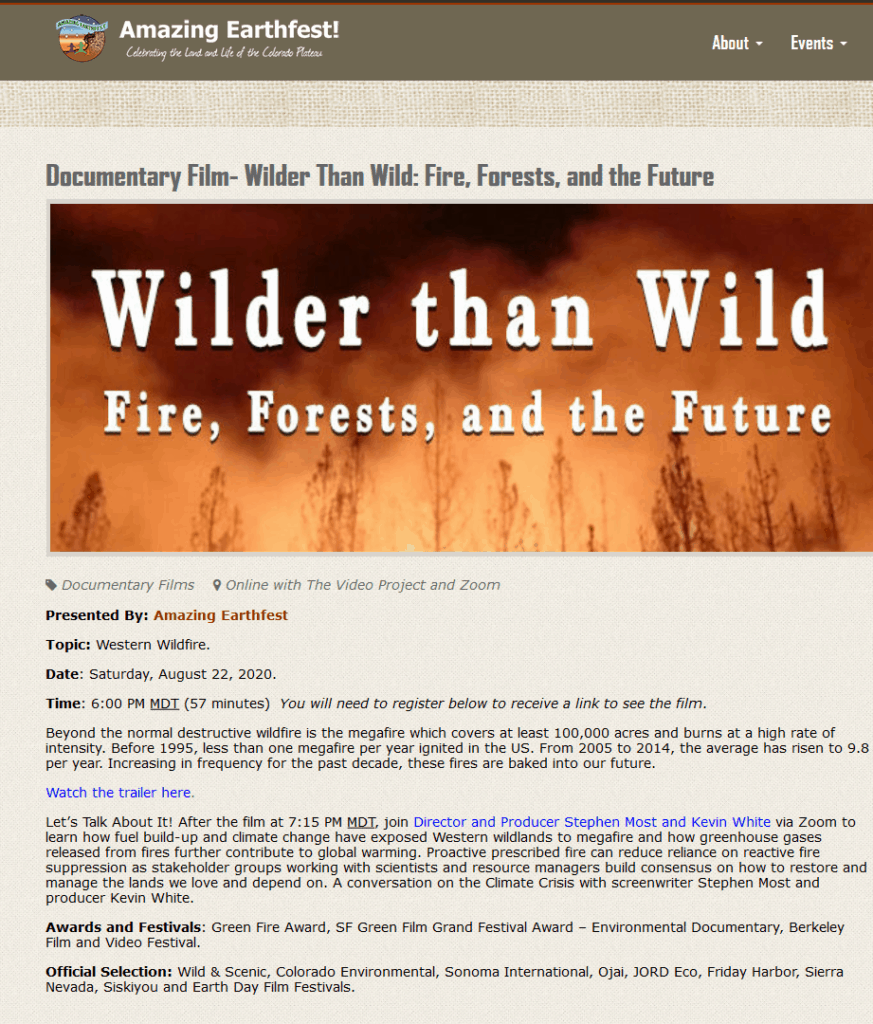

Matthew posted this by Doug Bevington about a documentary that elicited some discussion, but since it was shown by different stations across the US at different times, it was hard for us to see it together and discuss.

Stephen Most told me that Amazing Earthfest has a discussion of it on their schedule of events for August 22 at 6pm MDT. You can see Wilder than Wild online for free plus a Q & A with Stephen Most and the director, Kevin White, after it streams. You just need to register here, at the Amazing Earthfest site. Once you’ve registered, they provide a link so that you can view the film.

I watched the film and then re-read Bevington’s post, which, as you may recall started with:

Unfortunately, the filmmakers have chosen to make glaring omissions—excluding key scientific and environmental voices and leaving out essential facts—that cause their film to distort these issues more than it informs. As a result, the film gives cover to policies that are harmful to forests, dangerous for public safety, and detrimental to the climate, while steering attention away from genuine solutions.

I suppose it goes without saying that I did not see it that way.

What the film said to me is that:

1. Wildfires can do bad things to people, wildlife and their habitat, and watersheds.

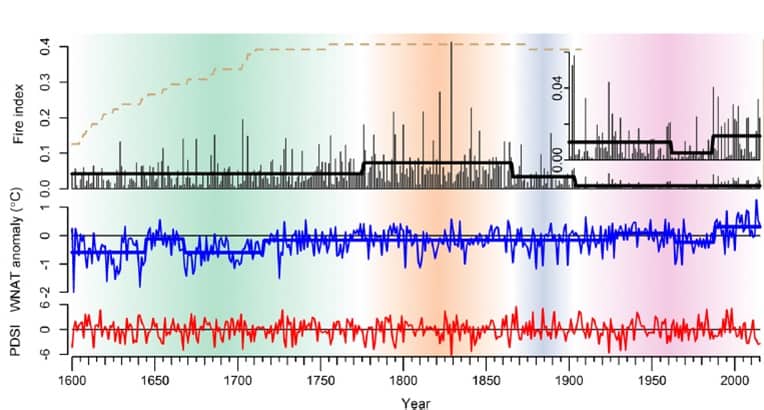

2. Climate change will make things worse.

3. To protect things humans value, plus places where other creatures can live, we need to use PB and WFU.

4. Native Americans managed land using burning, and so PB has been used for thousands of years before Native Americans were killed off and displaced.

5. Given changed conditions, vis a vis people and climate change, we need to work together to figure out what is best for our mutual futures.

I don’t know how anyone can argue with these, but am willing to have the discussion in the comments.

The film also calls into question some of the proposed solutions:

6. Some have said that the solution is for people to move somewhere else -out of the WUI- but you just can’t move entire towns and cities away. Plus the population is growing, and major cities have housing costs that are so high, people move farther away for affordability. There’s no way to force people to pay high rents for tiny places. The film says that there are 50 million folks currently living in the WUI.

7. Some have said something along the lines of “if you just protect 100 feet around your home, everything would be fine.” But the film shows a variety of infrastructure other than structures that are burned. Is a solution to make communities more fire-resilient? Yes. Is a solution also to keep fires out of cities and towns? Also yes. Is this controversial or wrong?

Finally, I thought it was interesting that people used the concept of “ecosystems evolving with fire”- but if Native Americans are thought to have been in California for 19000 years then the ecosystems evolved with Native Americans’ use of fire. We also know the climate has been changing for that time period, such that then we can’t really go back to a pre-Native American time (if we wanted to pick a human-free time). It seems that we’d have to say “the Native Americans got it right and that’s where we need to go even though the climate has changed since they were killed off” or “everything’s changed, given our values for species and people’s needs, we’re going to have to muddle through together.”

My own observations:

* Great videography of the fires and post-fire from above.

* There’re photos that show an old growth forest before and after an intense fire that certainly gives you the impression that at least some fires are not good for old growth and old-growth dependent species.

* Note that Calfire and the Park Service have prominent role in the film- hard to fit in the framing that it’s all about the FS wanting to log.

* The film shows the personal impacts of having a fire run through your community. In the El Paso County (Colorado) offices, we used to have an art exhibit created by people impacted by the Waldo Canyon Fire. These stories of personal impacts of wildfire I think are important to hear. Because (at least here) we do all need to work together, to keep fire out of communities, to evacuate, to house the people and animals, to tolerate PB smoke, and so on.

Quibbles:

If the quote about FS vs. NPS policies seemed not what you remember from the past… here’s an article by NPS that goes into more detail.

One thing that seemed to fit that wasn’t mentioned was the liability problem with PB. But this documentary was about California, and perhaps that is not a problem there.

Your thoughts?