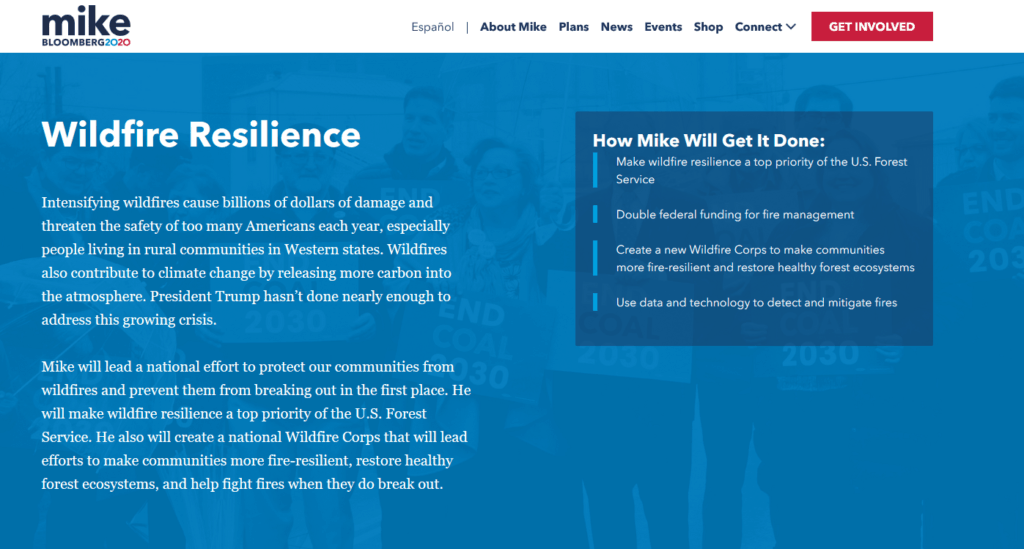

WildEarth Guardians noticed that the Forest Service is approving more and more vegetation management projects using categorical exclusions from NEPA procedures: “a category of actions which do not individually or cumulatively have a significant effect on the human environment.” They decided to do a little research, and found someone to report on it.

Rissien used Forest Service postings to tally all the logging and/or burning projects proposed for the past quarter – January through March – where forest managers had applied a “categorical exclusion” to avoid the public process normally required by law.

For just those three months, 58 national forests– that’s three-quarters of the forests in the West – proposed 175 projects that would affect around 4 million acres.

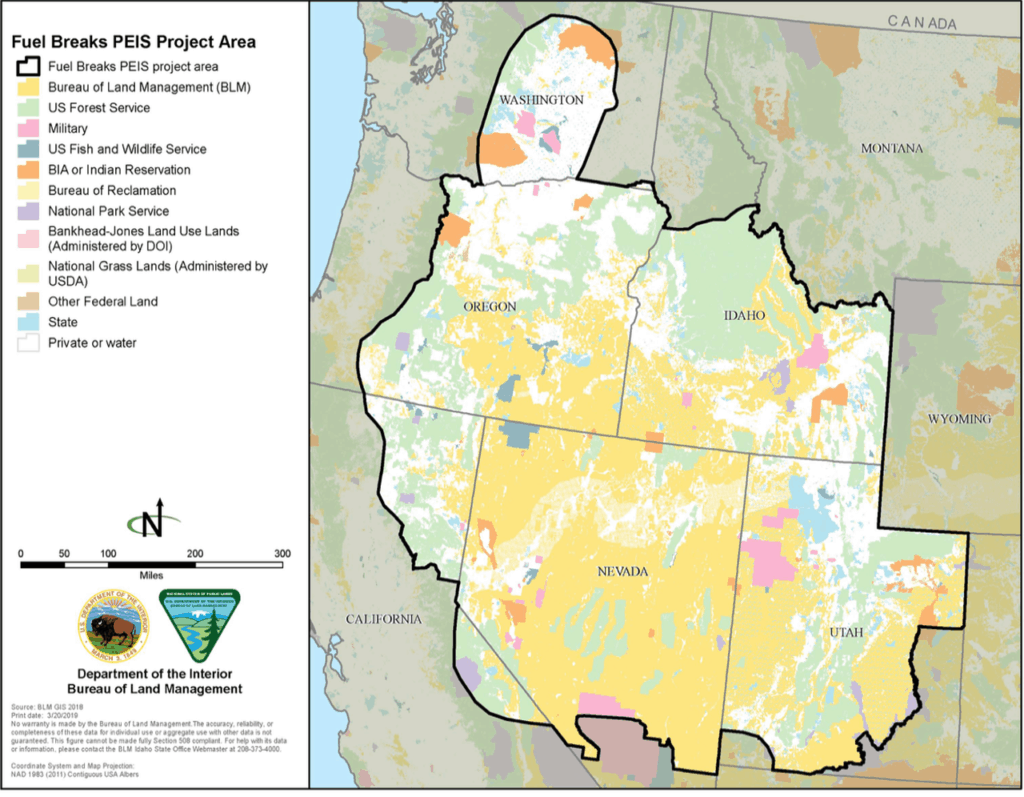

Rissien found, during the past quarter, USFS Region 4 – which covers southern Idaho, Nevada and Utah – proposed four projects that exceeded 100,000 acres each. One was 900,000 acres alone.

USFS Region 1, which includes Montana, northern Idaho and North Dakota, proposed 30 projects with CE’s last quarter, totaling more than 215,000 acres.

Logging projects intended to reduce insect or disease infestation or reduce hazardous fuels can be as large as 3,000 acres with some limitations. One CE created by the Forest Service for “timber stand and/or wildlife habitat improvement” has no acreage limit. Rissien found the Forest Service uses that for a majority of projects, and doesn’t even give a reason for others.

(There is also the “road maintenance” CE that has been the subject of litigation, including EPIC v. Carlson, here.)

There are some things to question in the article, but the slant of the article is not so much that what the Forest Service is doing is illegal, but that it is being done without much public information or awareness. The article also points out that the Forest Service just seems to be following its marching orders from the president. Tracking through the links gets you to this letter from the acting deputy chief, which says:

Consistent with this direction, Regional Foresters are to ensure that the Agency meet minimum statutory timeframes for completion of National Environmental Policy Act documentation and consultation with regulatory agencies. Categorical exclusions to complete this work should be the first choice and used whenever possible. I encourage you to explore creative methods and set clear expectations to realize this priority effort.

There’s a few points to make here. I’m not aware of any “minimum statutory timeframes” for NEPA or consultation (the consulting agencies do have a deadline for providing a biological opinion). I would translate “explore creative methods” into “take legal risks.” Artificial deadlines aren’t creative, but they also result in legal risks. Last is the implication that the use of categorical exclusions somehow avoids the need for an administrative record that shows that the use of the categorical exclusion isn’t arbitrary – that it fits the requirements of the category and does not have any extraordinary circumstances that could result in significant effects. The lack of public review or an administrative objection process may save time, and it forces an opponent to sue, but it increases the risk of losing the case on an issue that could have been resolved before the decision. (But if it gets points on the board during the game, does it matter what happens after?) WEG said, “But we have to take their word for it since there is no supporting analysis we can review.” If that’s what is really happening, it would eventually be a problem for the Forest Service in court.

Copyright: Photowitch | Dreamstime.com

Copyright: Photowitch | Dreamstime.com