The Western Governors’ Association has been having a Working Lands Roundtable with sessions on different topics. I previously posted on a session here. Here is a link to the presentations- they are all on video. Nothing “newsworthy” happened there. For me, as a retiree who doesn’t work daily with the folks slogging through this kind of work, I realized how much the media I read influences the way I think about what’s going on in the world. In our forest policy arena, that means that controversies are visible (Bernhardt! Bears Ears!) and the day-to-day work (and non-partisanized successes) mostly invisible. Speakers mostly discussed what they wanted to do together, what is helpful and what is problematic, as kind of a large-scale team effort; to be sure, influenced, but not circumscribed by, the shifting winds of DC politics and the randomness of court cases.

I’ve mentioned before that sometimes there is a contrast between “people who deal with ideas about things” and “people who deal with things.” Ideas about things are usually part of academia, other kinds of researchers, and think tanks. Ideas about things can also be part of partisan narratives, or narratives promoted by unknown funding sources for their unknown reasons. “People who deal with things” include firefighters, county commissioners, homeowners, agency employees, farmers and ranchers, and so on. These WGA workshops are relatively unique in that the speakers tend to be people who deal with things.

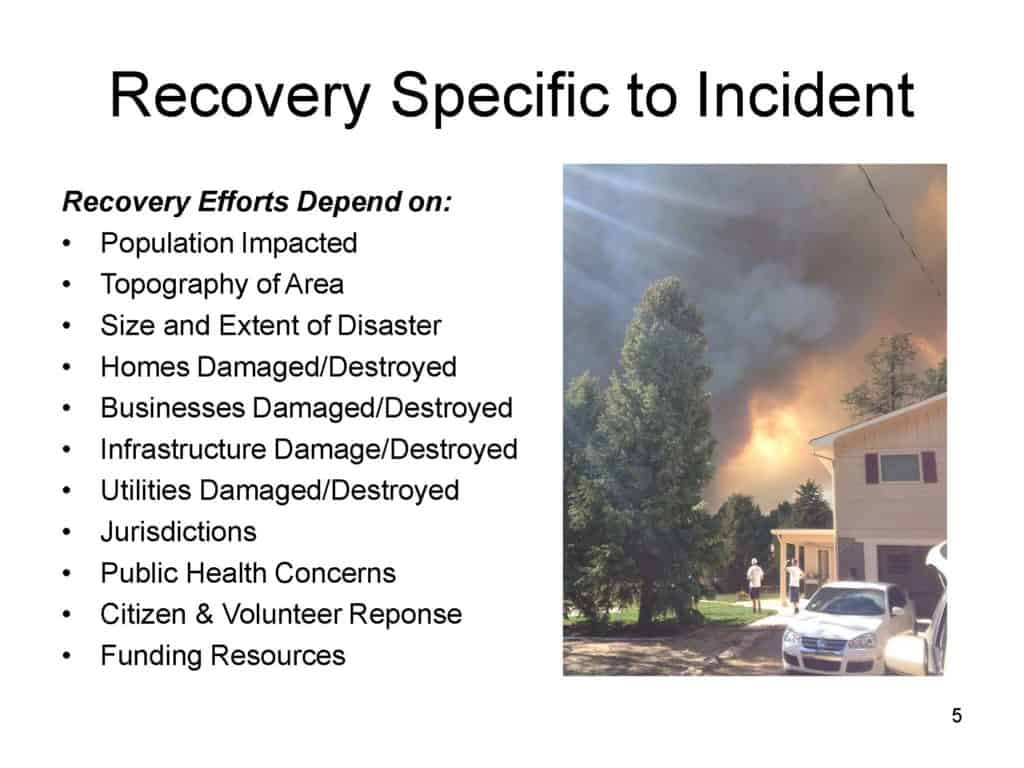

For example, I think this Youtube clip of a talk by former El Paso County Commissioner Sallie Clarke shows what it’s like to be on the ground working with communities during and post fire. Clarke’s presentation caused me to reflect on her and El Paso County’s experience compared to some of the ideas that are floating around out there.

(1) One is “wildfires wouldn’t be a problem if people wouldn’t build houses in fire prone country.” New building may increase the acreage with house, infrastructure and evacuation problems, but fires are still problems with the towns, cities and communities that are already built. Plus the communities downstream from where the big fires are. So being careful about adding buildings is important, but will not make wildfire/human problems go away.

The second idea is often associated with Jack Cohen’s work on structures and says that (2) if you want to protect homes or other buildings, you need to focus on fire-resilient building materials and a zone close to the house. Again, that is an academic answer framed as being about structures, not people in communities. The approach again, is important but not sufficient. No one wants fire burning through their communities, even if it doesn’t burn down their houses and neighborhood infrastructure. Talk to someone who has lived through an evacuation. Talk to someone who has large animals to move during an evacuation, which is not uncommon in El Paso County. Talk to someone who was trying to evacuate and the roads were blocked, and had to decide whether to leave the car and run for it. Just.. not a good idea.

(3) The third idea is “you don’t need fuel treatments if the treatments are not adjacent to houses.” Yet wildfires can cause flooding that is often not good for the environment and destructive to communities and people- anywhere downstream. We often hear about “the vegetation needs high intensity fires to return to HRV or NRV” but it’s not all about the veg. Do hydrologists or fish bios get to weigh in on their own “desired range of variation?” Wildfires not directly adjacent to communities can still impact them via flooding, silting up reservoirs and other impacts.

For some reason, post-fire flooding doesn’t seem to get the media or academic coverage that wildfires do themselves. Perhaps there’s no controversy or drama. But if you want to get a feel for the things people need to do to slow water and reduce flooding post-fire, and the collaborations involved, check out Sallie Clark’s presentation or slides.