Here’s the simple framing of the way the reporter reported it: 1)There are lots of dead trees 2) to change fire behavior, and reduce fuels you need to do something, with at least some with them 3) it’s better to do something useful with them than to burn them in piles, or not do fuel treatments at all. If it doesn’t work out for energy, there are still many potential uses for forest products. I think sometimes when folks hear “biomass” nowadays they get into the “biomass burning for energy” controversy and may unintentionally think right past other, less high-tech, and possibly less controversial, uses.

The ‘perfect lab’

When Phil Seligman looked at the Rio Grande National Forest in early 2013, he saw land that was ripe for wildfire.

“This place was ready to pop,” said the president of Wood Source Fuels, noting that intense drought and beetle kill facilitated the explosion of the 109,615-acre West Fork Complex fire later that summer.

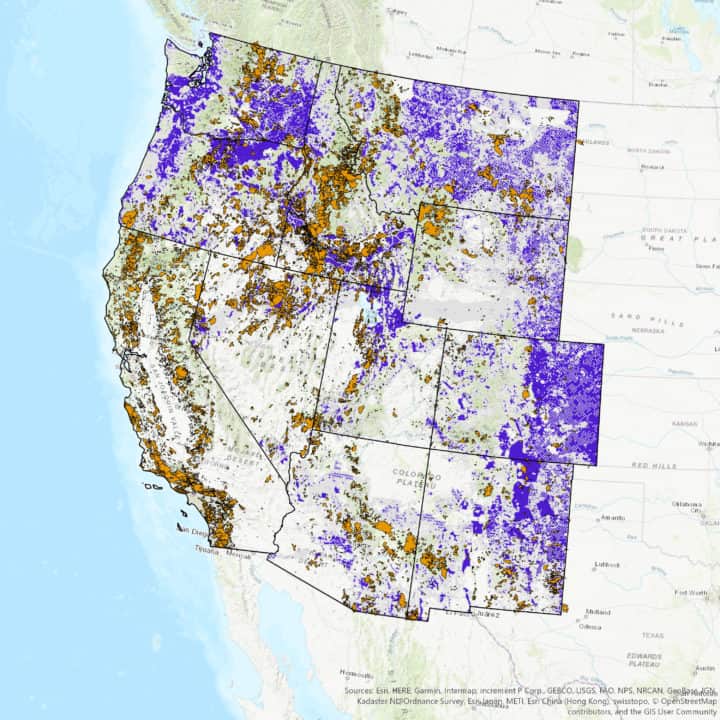

In Colorado, more than half a million acres of trees were impacted by insects and diseases in 2017, Colorado state Forest Service reported. For the sixth year in a row, spruce beetle was the state’s most widespread and damaging forest insect pest, with 206,000 acres of active infestations detected, about 67,000 of which were new.

Since 2002, 617,000 acres of high and midelevation forests in the Rio Grande have been infested by spruce beetles. Although spruce beetle activity has decreased dramatically (from 93,000 acres in 2016 to 47,000 acres in 2017).

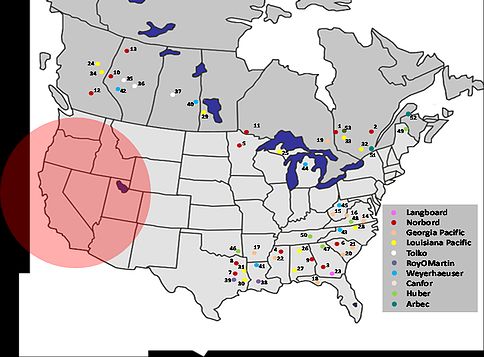

Seligman has shipped timber with Union Pacific Railroad for more than 10 years, building a network of partners in the logging industry across the country. In 2010, he became involved with biomass after Tri-State Generation & Transmission asked him and Nate Anderson, a research forester with the Rocky Mountain Research Station, to conduct a study on the viability of generating electricity from biomass at the Nucla Station power plant. He estimated that biomass was almost as cheap as coal.

Although Tri-State passed on the opportunity to adopt biomass as a fuel source, the study planted the seed of cooperative forest management in Seligman’s mind. Seligman then arrived in the San Luis Valley and found a “perfect lab” to continue the work on biomass utilization that he and Anderson had started in Nucla. In addition to biomass, other end uses can include everything from landscape chips to animal bedding, with companies already expressing interest.

Unlike in most laboratories, though, Seligman’s work in the Rio Grande National Forest could alter its wildfire conditions for generations to come.

An unprecedented partnership Seligman met Dallas, and the two began the uphill battle to form a cooperative that engages every player in the biomass market: buyers in the across the county and overseas, Union Pacific Railroad, an insurance company, tire distributor and forestry equipment dealer, among others.

After years of arduous negotiations, Seligman secured a $231,700 Wood Innovations Grant from the U.S. Forest Service in 2017 to create the cooperative — Forest Management & Marketing Limited — and invest in market expansion.

“The co-op represents people who see potential in our forests to be healthier and a resource,” Dallas said. “All you have to do is look at a map of the Union Pacific Railroad and see that it has tracks that go through other forests and almost any of those forests have a large scale die-off for one reason or another.”

Seligman said, “This was a tool built for the Forest Service. We feel that working with an entity like this that gives the Forest Service necessary contracts that they need but have historically had trouble getting.”

A critical collaborator is the Union Pacific, which will transport the biomass to processors and producers.

The cooperative plans to start construction as early as December on a chip plant in Antonito that would employ six to seven people and pull wood from the Carson and Rio Grande national forests.

If Seligman’s biomass estimations add up, they could build a larger biomass conversion plant that would employ about 200 people and source from the Carson, Rio Grande, San Juan and San Isabel national forests.

In the Rio Grande National Forest, 3,208 acres (and growing) are available for biomass harvest.

“We have a continental-scale problem, so if we can involve four forests, that’s a big deal,” Seligman said.

The extra jobs from the chip and conversion plant, the railroad, on-the-ground logging, and other related operations could bring economic help to one of Colorado’s most distressed counties. Between 2016 and 2017, Rio Grande County lost 11.5 percent of its businesses and 10.9 percent of its employment. Its poverty rate is 19.2 percent at a time when the state as a whole added 14.3 percent more jobs and expanded its business sector 7.2 percent.