New research has taken an exponential leap forward in measuring air pollution from forest fires. It confirms the importance of sound forest management in terms of health. To summarize: prescribed burns are significantly more desirable than wildfires. “Researchers associated with a total of more than a dozen universities and organizations participated in data collection or analysis. The scientists published their peer-reviewed results on June 14 in the Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres.” Georgia Institute of Technology was cited as the lead university and Bob Yokelson, a professor of atmospheric chemistry at the University of Montana were specifically mentioned in this article from ScienceDaily.

Some quotes from the article include:

1) “For the first time, researchers have flown an orchestra of modern instruments through brutishly turbulent wildfire plumes to measure their emissions in real time. They have also exposed other never before measured toxins.”

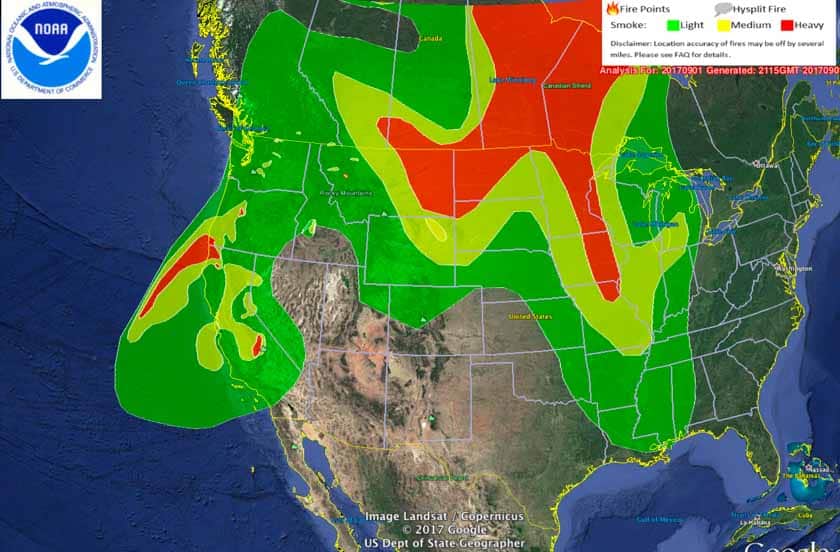

2) “Naturally burning timber and brush launch what are called fine particles into the air at a rate three times as high as levels noted in emissions inventories at the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, according to a new study. The microscopic specks that form aerosols are a hazard to human health, particularly to the lungs and heart.”

3) “Particulate matter, some of which contains oxidants that cause genetic damage, are in the resulting aerosols. They can drift over long distances into populated areas.

People are exposed to harmful aerosols from industrial sources, too, but fires produce more aerosol per amount of fuel burned. “Cars and power plants with pollution controls burn things much more cleanly,””

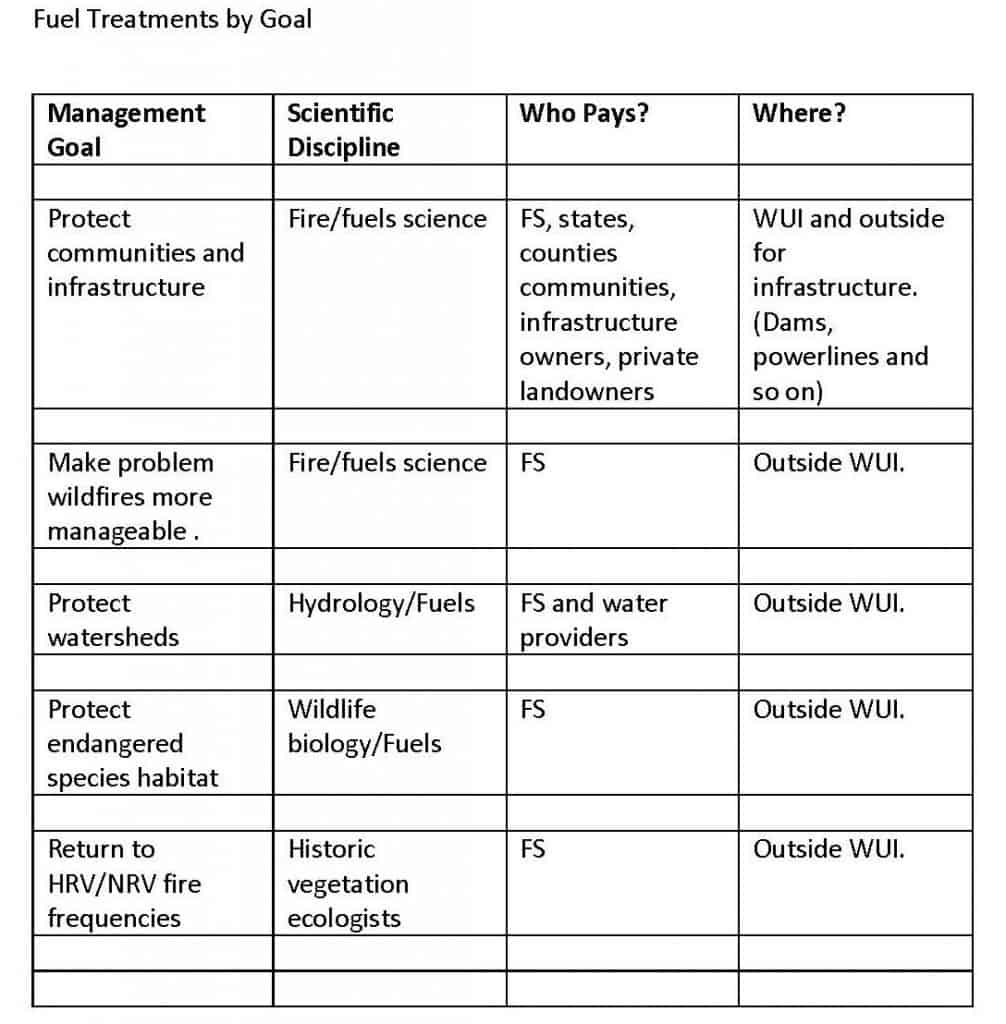

4) “”A prescribed fire might burn five tons of biomass fuel per acre, whereas a wildfire might burn 30,” said Yokelson, who has dedicated decades of research to biomass fires. “This study shows that wildfires also emit three times more aerosol per ton of fuel burned than prescribed fires.”

While still more needs to be known about professional prescribed burnings’ emissions, this new research makes clear that wildfires burn much more and pollute much more. The data will also help improve overall estimates of wildfire emissions.”

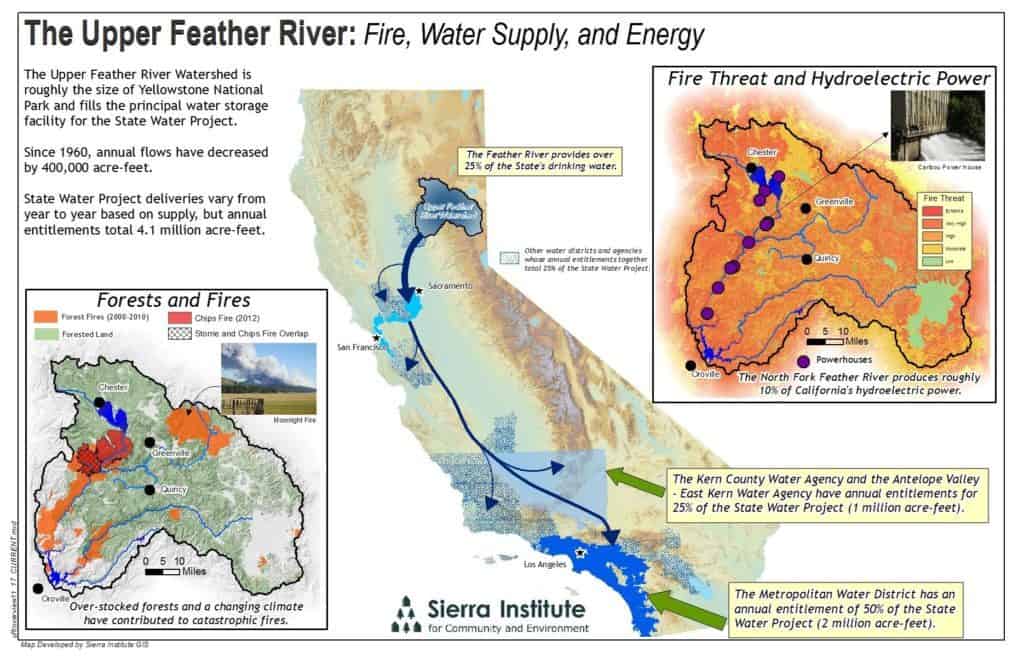

I feel that the previously expressed concerns by many of us about the impact of wild fires on human populations for a thousand or more miles from a catastrophic fire have been reinforced, once again, by this landmark research. It matters not whether you are for or against human intervention to minimize the risk of catastrophic fires; sound, sustainable, science based forest management to accommodate human health and other needs in harmony with the needs of forests and their dependent species (as a whole system) is in the process of restoring some balance to piecemeal, emotionally driven, faux science and wishful thinking. Save the planet – save our forests – use statistically sound, replicated research validated by extensive operational trials over time and place to make sound environmental decisions.