The last few posts have been about what we might call “fuel treatments at the stand level.” Now we can move on to “fuel treatments on the landscape.” To that end, the next few posts are based on interviews with a scientist who specifically studies “where to put fuel treatments on the landscape.” Dr. Mark Finney, is the originator of SPLATs or “strategically placed landscape treatments.” Mark is a well-known fire scientist at the Missoula Fire Lab. Here is a link to his profile at Rocky Mountain Research Station (warning: people who study fires in action, and deal with fire suppression have more acronyms than you can shake a drip torch at.) Here is a more list of publications.

Below are my questions and his answers.

What is a “SPLAT”?

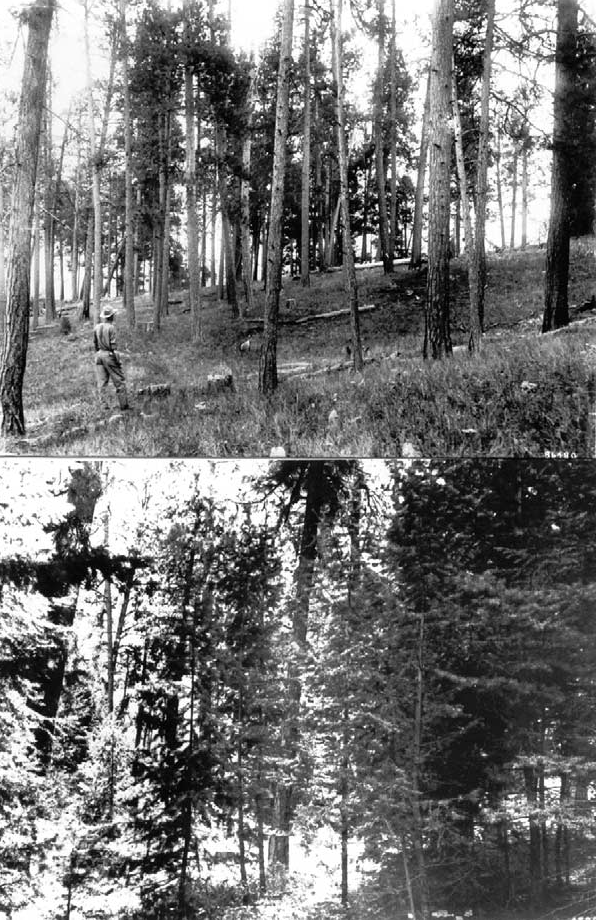

It stands for “strategically placed landscape area treatments.” They may also be called SPOTs for “strategic placement of treatments.” It derives from the theory that separate treatment units must overlap in the primary heading direction of the fire to interrupt routes of fires. The concept is not to stop fires, but to change the behavior, including spread rate and intensity. The pattern of disconnected treatments can interrupt the movement of the fire to reduce the intensity, buy time for weather to change or for suppression efforts. There can be an aggregated benefit if they are designed properly.

What’s the difference between a SPLAT and a fuel break?

A “fuel break” is a designed defensible location that requires active suppression. There is a long history of ineffective fuelbreaks. There have a number of limitations for landscape scale uses. First, they are intended to stop fires, and if they don’t then they’re not successful even if they modify fire behavior dramatically (lots of examples of green fuel breaks that are black on both sides). Second, stopping large fires on fuel breaks rarely succeeds because the length of the fuel break impacted by the fire perimeter requires too many personnel for suppression. Third, fuel breaks have to be maintained – which can become quite a burden in perpetuity. In contrast to the landscape objectives, fuel breaks are useful near areas of high value (structures) where defensive actions are going to be occurring anyway – reduced fire behavior will be very beneficial to protection even if the fire doesn’t stop (i.e. spots over).

How do you know where to place SPLATS?

They must overlap the primary wind heading direction. How do you know what wind direction?

In a given area, there can be a common wind direction from previous fires. “Large fires” are also called “problem fires”, from Bahro et al 2007. “A “problem” fire is a hypothetical wildfire that could be expected to burn in an area that would have severe or uncharacteristic effects or result in unacceptable consequences.” These past fires can give you a lot of information. You can use that information to find out how spread usually works in an area, usually or two main directions. You can look at fire weather and fire history and use that information to design treatments against exactly those fires.

What about size of individual treatment units? Ideas come from modeling. In the modeling, there is no exact size, it’s more about the pattern. In practice, there are a number of factors, one is operational constraints, one is the size of fire you are trying to interrupt. You can’t make them so large that fires can fit between untreated ones. Then you have to factor in spotting. Past suppression removes mild and moderate conditions, so now we have spreading under most extreme conditions, with more spotting. If, for example, spotting is ¼ mile then you need to have a ¼ mile. In theory, they can be small or big and they don’t have to be all the same size. You can choose them to fit terrain, ownership and roads. You can work around areas in which you can’t do the treatments.

To actually implement them, you need the to design them, work through the NEPA and appeals process. Through the appeals process, maybe you have to redesign everything if you can’t do a particular unit. But you can take that unit out and rerun the modeling and see what the impacts are and see if you need to redesign other units or add another unit.

The next post in this series will be on SPLATS in practice.