26 years after “protected” forests burned, in Yosemite National Park, this is what we now have. Chances are, it will burn again, before conifer trees can become established enough to resist the next inevitable wildfire. You might notice that even the manzanita is having trouble surviving. I doubt that John Muir intended this on public lands. This landscape is probably the future of parts of the Rim Fire, within Yosemite National Park.

History

Update From the Yosemite “Laboratory”

Here is a stitched-together panorama from the Foresta area of Yosemite National Park. I’ll have to pair it up with my historical version, one of these days. Restoration processes seem to be minimal, as re-burns continue to ravage the landscape, killing more old growth forests and eliminating more seed sources. Even the brush is dying off, due to a lack of organic matter in some of those granitic soils. With the 200-400 year old trees gone, we have to remember that these stand replacement fires, in this elevational band of the Sierra Nevada, weren’t very common before the 1800’s.

Yes, it IS important that we learn our lessons from the “Whatever Happens” management style of the Park Service. Indeed, we should really be looking closely at the 40,000+ acres of old growth mortality from the Rim Fire, too! Re-burns could start impacting the Rim Fire area, beginning this fire season.

Yes, it IS important that we learn our lessons from the “Whatever Happens” management style of the Park Service. Indeed, we should really be looking closely at the 40,000+ acres of old growth mortality from the Rim Fire, too! Re-burns could start impacting the Rim Fire area, beginning this fire season.

Big Burn Premieres on PBS Tonight!

Time to program your DVR’s..

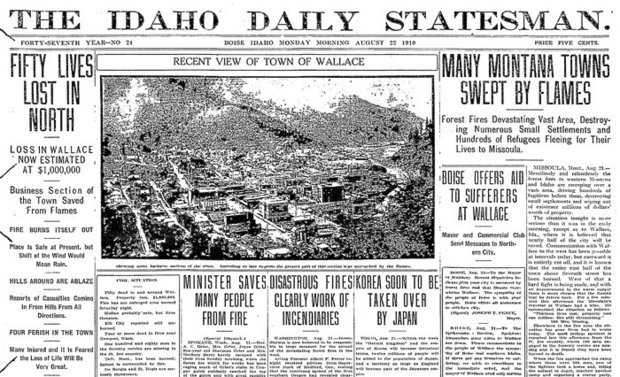

From Rocky Barker of the Idaho Statesman..here..thanks to Ron Roizen of the Not Without a Fight blog.

Here’s the link.. there’s a preview.

Throwback Thursday, Yosemite-style

I’ve found my hoard of old A-Rock Fire photos, from 1990! I will be preparing a bigger repeat photography article, after I finish selecting and scanning. Like several other fires this summer, the A-Rock Fire started in the Merced River canyon, burning northward. I really believe that this is the model of what will happen to the Rim Fire, if we do nothing to reduce those dead and dying fuels. Active management opponents never want to talk about the devastation of re-burns, as an aspect of their “natural and beneficial” wildfires. Most of those snags have “vaporized” since this 1989 wildfire. Indeed, this example should be considered when deciding post-fire treatments for both the Rim Fire and the King Fire, too.

It should be relatively easy to find this spot, to do some repeat photography, along the Big Oak Flat Road.

In Idaho, Tracing What Remains After the Flames

Dick Boyd sent me this article featuring the Sawtooth National Recreation Area. The Stanley area is one of my favorite spots, with hot springs, jagged peaks, pristine lakes, spacious meadows and abundant wildlife.

As we neared Stanley, Idaho, a hamlet carved by creeks and framed by mountains with spiky peaks that reminded me of a punk rocker’s hair, the landscape surrounding the winding highway on which we’d climbed 7,000 feet gave way from rugged canyon to flat expanse of grass speckled by lodgepole pine and aspen. We were on the northern edges of the Sawtooth National Recreation Area, three hours from Boise, when scars from an old fire came into view.

My daughter, Flora, and I had been playing a makeshift game in which we pointed out the nature surrounding us, the sort of mindless thing you do to entertain a 5-year-old on a road trip. I see a deer, I see a birdie, I see snow, I see a purple flower, we called out.

“I see trees,” I said, pointing to a cluster of an unrecognizable species to our left, their crooked branches denuded by flames that had torched them.

“Those are not trees,” Flora retorted. “Trees have leaves!”

This article reminded me of the time I spent working on the Boise National Forest, after the massive 1994 Rabbit Creek Fire took 2 months to burn before the Sawtooths and fall rains finally extinguished it. The public rarely sees any of the 150,000 burned acres, as it isn’t visible from the highways. I stumbled upon this vintage video that shows how devastating such fires can be, as storms deposit moderate rains upon highly hydrophobic soils.

It is not always easy to display the damages that occur when soils cannot absorb even moderate rainfall. As the storms and high winds came in, that day, Forest Service employees were called in, due to the danger. Oddly enough, they forgot about me. I weathered the storm, not knowing what was happening. The next day, I patrolled the roads, finding a plugged culvert, with excessive soil movement. I pulled out my trusty shovel and diverted all the water into the roadside ditch, getting it to flow down and through the next downhill culvert.

A Footnote to “How Long Has This Been Going On?”

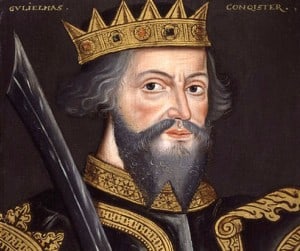

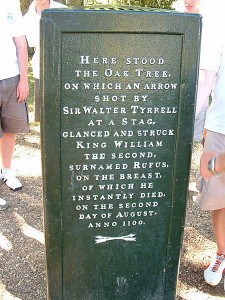

On May 3, a couple of days ago, I posted a little article at our “Not Without a Fight!” blog on the interpretation of King William Rufus’s death by medieval English historians and, thereafter, by generations of the British people. Rufus was the third son of William I or William the Conqueror, he who famously defeated the Anglo-Saxons in the Battle of Hastings in 1066. Rufus, who succeeded his father on the throne with the latter’s death in 1087, died in mysterious circumstances in 1100 in a place called the “New Forest.” This “New Forest” was a huge area declared by fiat as a hunting preserve for William the Conqueror and his noble friends in 1079. It was very unpopular, according to medieval English historians anyway, among English commoners and especially those displaced by the King’s bold edict. These same historians were fond of attributing Rufus’s death, as well as the deaths of two other members of William I’s family, to divine retribution for the King’s destruction of locals’ homes, livelihoods, villages, and churches with the New Forest’s creation.

More recent historical study — beginning, oddly enough, with a commentary on this history by Voltaire in 1753 – has questioned whether William I’s New Forest was as disruptive to local communities as medieval historians claimed. Despite more than a little evidence that undermines the old, medieval account, that account seems to have survived quite well in the popular mind or English folklore.

Now, you might be wondering why I would have bothered to recount this story on a blog site devoted to the looming economic and social crisis faced by U.S. counties with considerable acreages of national forest. Well, it all began a couple of weeks ago when our old TV gave out. We bought a new TV and its remote came with a Netflix button, for streaming videos from that source. One of the shows I began watching via this new source was David Starkey’s brilliant, 17-installment series on the history of the British monarchy. As it happens, the series’ third program briefly touched on the story of the New Forest’s creation, King Rufus’s untimely accidental death, and the place of these events in British historical memory. My immediate reaction was: “I can use this!”

How?

Well, it struck me that the locking up of our national forests – by which I mean, in this case, the great decline in logging and forest management activity over the past two decades – has a very, very long history: i.e., stretching all the way back to the creation William the Conqueror’s New Forest in 1079. That’s very nearly a thousand years ago. It also struck me also that the persistence of the divine punishment interpretation of Rufus’s death in the English historical memory represents a kind of long term – indeed, very long-term! – symbolic price William the Conquer had to pay for his love of hunting and his creation of the New Forest. That price, in turn, might strike a cautionary note for today’s officialdom and their green friends, where these folks are (or appear to be) happy with the prospect of shutting down the multi-use of our national forests.

So that was my thought process. Unfortunately, the blog post didn’t communicate all of that as well as it might have – indeed, or even as well as I’ve communicated it here. Nevertheless I’d like to invite members of this list to have a look at this NWAF! post when and if they have a moment to spare for some very old history.

— Ron Roizen

Vintage Yosemite Photo

I’ve been digging through my old Kodachrome slides, and I found this view of the Tuolumne River and Poopenaut Valley, within Yosemite National Park. This area burned in the Rim Fire, and it is representative of what lies below, in the Stanislaus National Forest. Of course, little of this would even be worth salvaging, even it is wasn’t in the National Park. You might notice the abundance of digger pines, even on the north-facing slopes. This is the beginning of an impressive canyon, and it becomes a Wild and Scenic River, when you reach the Park boundary. Of course, very little fuels work could have been done, within this awesome canyon. However, fuelbreaks could have been installed all along the edge of this canyon, knowing that there would eventually be an ignition, within the canyon. Lightning fires happen all the time in this portion of the Sierra Nevada. I really want to get in here and re-visit these spots, for some repeat photography.

Pinchot’s Promises to Counties: History Remembered

Congress recently passed and the president signed a one-year extension of Secure Rural Schools (SRS). Most commentators, however, see dim prospects for SRS’s renewal beyond 2014. The SRS program has been widely characterized as an interim safety net and transitional measure intended to tide counties over a period of dwindling timber harvests on national forests. It’s been said – even back in 2000, when SRS began – these payments were never intended as a long-term or permanent federal program. SRS would merely lend counties a hand as they shifted and diversified their local economies, making them less dependent on federal timber harvests.

Yet, this characterization of SRS misrepresents and misremembers a deeper and ongoing federal obligation to counties with national forests. Congress enacted a 10 percent timber revenue sharing measure in 1906, only a year into the Forest Service’s young life, and then raised the county share to 25 percent in 1908. The sharing provision sprang from a general recognition that counties hosting national forests suffered hardships on that account. Most notably, wherever national forests were laid out, counties lost potential property tax revenues, which in turn implied an increased tax burden for private landowners. Property taxes collected by local governments have traditionally supported schools, roads, police and fire protection, libraries, and other local services. Federal ownership also blunted potential growth in population and commerce. Moreover, counties retained the responsibility and expense of maintaining roads in national forests. The national forest land grab was by no means trivial. Here in Idaho almost 40 percent of the state’s area was appropriated for national forests. In our county – Shoshone County, Idaho – fully 72 percent is national forest.

Small wonder Idahoans and other westerners fought vigorously against the great and rapid expansion of forest reserves and national forests in the first decade of the 20th century. For his part, Gifford Pinchot, the national forest system’s great architect and advocate, sought to reassure westerners that their perceived negatives were really positives. In his 1907 book, The Use of the National Forest, Pinchot argued that federal forest ownership wouldn’t limit the uses of these lands but instead would insure that they achieved their highest use. The homesteader, the miner, the stockman, and “the small mill man” could go about their enterprises unfettered by the national forest designation, Pinchot confidently suggested.

Pinchot specifically addressed the issue of lost county property tax revenues in a section of the book titled “What happens to county taxes?”

“People who are unfamiliar with the laws about National Forests,” wrote Pinchot, “often argue that they work hardships on the counties in which they lie by withdrawing a great deal of land from taxation. They say that if the lands were left open to pass into private hands there would be much more taxable property for the support of school and road districts. The National Government of course pays no taxes. But it does something better. It pays those counties in which the Forests are located 10 percent of all the receipts from the sale of timber, use of the range, and various other uses, and it does this every year. It is a sure and steady income, because the resources of National Forests are used in such a way that they keep coming without a break.”

From the get-go, the chief purpose of the Forest Service’s timber revenue sharing was compensation for lost county property tax revenue. This provision was a foundational feature of the new Forest Service agency. Huge expanses of national forest land inevitably imposed (and continue to impose) great losses in property tax revenues upon counties. SRS, initially passed in 2000, provided for compensation of counties when timber revenue broke down. When SRS sunsets after 2014, however, the federal obligation to compensate for lost property tax doesn’t evaporate. Property tax is collected year-by-year by counties. Hence, compensating for lost property taxes isn’t a one-time, sometime, or time-limited matter. In our county – as in many counties – three years of delinquent property tax payments results in a property’s title being transferred to the county. Come to think of it, we’re not averse to applying the same principle to our county’s national forest lands. We need a long-term solution to the issue.

This column was written by the following: Jim Best, Leslee Stanley, and Larry Yergler, Shoshone County commissioners; and Chris Asbury, William Woodward, Robin Stanley, Dr. Robert Ranells, school superintendents in Avery, Kellogg, Mullan, and Wallace (respectively).

The Future of the Rim Fire?

These are 2011 views of the A-Rock/Meadow Fire re-burn, within Yosemite National Park, after 4 years of “recovery”. The actual “recovery” time is now at 24 years, since the original A-Rock Fire raged through majestic old growth. You can barely make out the road into Yosemite Valley. You might also notice a lack of any conifer trees growing back.

Even fire-adapted oak trees are doing very poorly, and the large snags from the previous stand, before the A-Rock Fire in 1989, are completely gone. Remember, no salvage logging happened away from roadside hazard trees.

This is how the Sierra Nevada “recovers” from catastrophic wildfires. It can take hundreds of years to re-grow a forest, without help from humans. Indeed, Yosemite is a living laboratory, and it is clearly showing us some “lessons learned”. It is also clear that any Yellowstone recovery parallel to Sierra Nevada wildfires is not supported by actual results.