Links in the headers are to documents or provide further links to them.

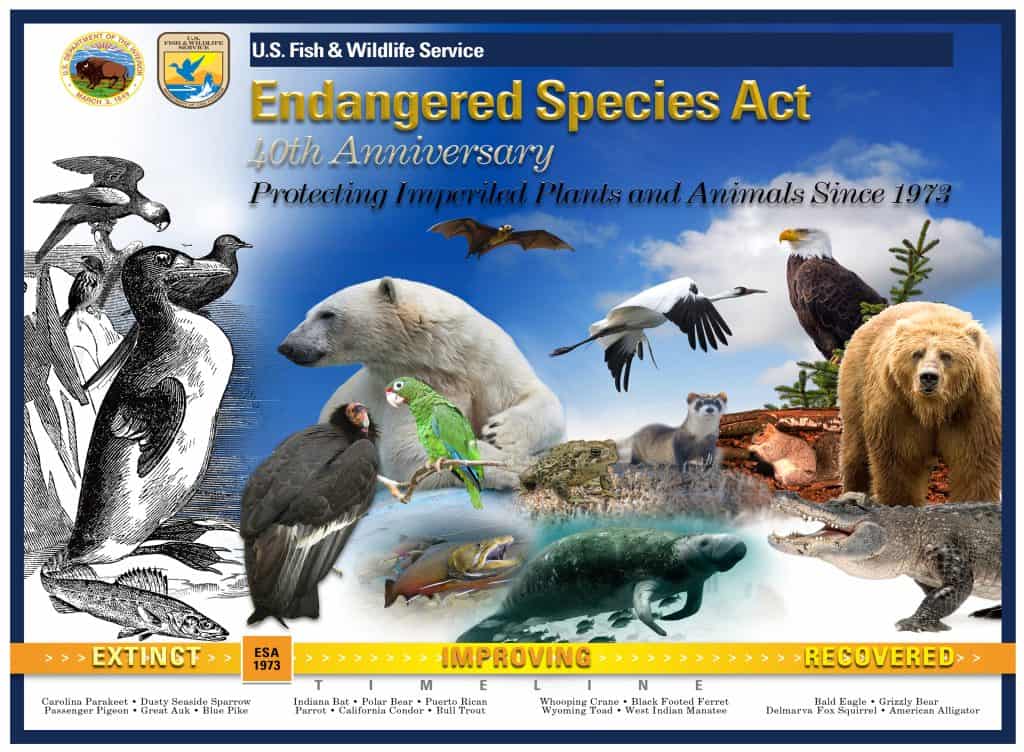

On February 28, the Center for Biological Diversity and the Maricopa Audubon Society notified the Forest Service and Fish and Wildlife Service of their intent to sue regarding ongoing grazing on the Coronado National Forest and a Biological Opinion on that from September 30, 2021. The species subject to ESA and allegedly affected by damage from cattle grazing in riparian areas are the yellow-billed cuckoo, northern Mexican gartersnake, Chiricahua leopard frog and Sonora chub. Here is a long background article.

Court decision in Oregon Natural Desert Association v. Bureau of Land Management (D. Or.)

On March 29, the district court denied a motion for a temporary restraining order against the BLM’s authorization of livestock grazing on pastures containing 13 Research Natural Areas for the 2022 season without providing fencing to exclude grazing from these areas, as required by the 2015 Oregon Greater Sage-Grouse Record of Decision/Approved Resource Management Plan Amendment. The court held that plaintiffs are unlikely to suffer irreparable harm to their use and enjoyment of the land, their interest in scientific research or to the sage-grouse population if the pastures are grazed this summer.

Court decision in Monroe County Board of Commissioners v. U. S. Forest Service (S.D. Indiana)

On March 30, the district court reversed and remanded the Houston South Vegetation Management and Restoration Project on the Hoosier National Forest because it failed to fully evaluate the potential effects of the Forest’s largest ever logging and burning project on the water quality of Lake Monroe (an important drinking water source). The court also denied claims related to the range of alternatives considered and effects on endangered bats. More information may be found in this article.

- Kilgore Gold Exploration Project

New filing in Idaho Conservation League v. U. S. Forest Service (D. Idaho)

Following a court loss in 2020, involving Yellowstone cutthroat trout (discussed here), the Caribou-Targhee National Forest approved a new plan put forward by the company involving road building and 130 drill stations for the Kilgore Gold Exploration Project. According to this article, plaintiffs contend they should be allowed to file a supplemental complaint because the new decision essentially repeats what the court previously rejected and violates various environmental laws.

On April 1, an administrative judge for the government’s Merit Systems Protection Board found that a seasonal firefighter was entitled to a hearing regarding his claims of retaliation against him for posting on social media about what he perceived as the agency’s lax COVID-19 rules during the pandemic, which could have endangered the health of his young son. The Forest Service agreed to award him $115,000 in back pay and remove him from “do not rehire” lists.

Court decision in Native Ecosystems Council v. Lannom (D. Mont.)

On April 4, the district court reversed the Castle Mountains Project decision on the Helena-Lewis & Clark National Forest for failure to comply with the forest plan requirement for elk that recommendations from the Montana Department of Fish, Wildlife and Parks “will be followed.” (Note: I think the Forest Service might have argued that such a standard is invalid because it defers forest plan decisions to a third party without public participation.)

The Forest misrepresented the recommendations regarding the effects of temporary roads, and failed to demonstrate that elk habitat effectiveness would be maintained or enhanced in accordance with those recommendations. They also improperly treated the forest travel plan as a fait accompli, even though it had largely not been implemented, and therefore it could not serve as a baseline for the effects of temporary roads. The court also held that the agency record “does not show that the agency complied with either NFMA or NEPA in relation to the undisputed decline in goshawk nesting territory.”

The court also construed the Roadless Rule’s exception that allows timber harvesting when “needed … [t]o maintain or restore the characteristics of ecosystem composition and structure, such as to reduce the risk of uncharacteristic wildfire effects, within the range of variability that would be expected to occur under natural disturbance regimes of the current climatic period.” “Need” does not require existing conditions to be outside of the range of variability, and the exception applied to “meadows restoration” and “whitebark pine restoration” in this case.

Court decision in Upper Green River Alliance v. U. S. Bureau of Land Management (D. Wyo.)

On April 5, the district court upheld BLM’s decision to allow Jonah Energy to continue its development of the 145,000-acre, 3,500-well Normally Pressured Lance gas field, which crosses the pronghorn migration route discussed here, and would occupy important sage-grouse habitat. The court found that the BLM met NEPA requirements for evaluating the effects. (Shortly afterwards, the same Department of Interior announced a $250,000 grant that will help secure a conservation easement in the wildlife corridor north of the future well-field. This article also discusses the lawsuit.)

On April 7, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (“Service”) issued an emergency rule under Section 4(b)(7) of the ESA listing the Dixie Valley toad (Anaxyrus williamsi) as endangered, and on the same day the Center for Biological Diversity filed a Notice of Intent to Sue the BLM and the company behind the Dixie Meadows Geothermal Utilization Project in Nevada, being developed in the toad’s only habitat. A prior (and still pending) lawsuit was discussed here, and this article provides additional background.

Court decision in Central Sierra Environmental Resource Center case (9th Cir.)

As reported in this article, on April 8, the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals affirmed the district court, and found that the Stanislaus National Forest had not violated reporting or discharge restrictions under the Clean Water Act regarding permits for their grazing allotments. Instead, a state agency is responsible for determining Forest Service compliance. (This case was discussed when it was filed here.)

Settlement agreement in The National Trust for Historic Preservation v. Haaland (D. Ariz.)

On April 21, the district court approved a stipulated settlement requiring BLM to re-examine its decision to allow target shooting in 90% of Sonoran Desert National Monument. They must consider an alternative that protects several areas of the monument. (The news release includes a link to the settlement agreement and the original complaint.)

New lawsuit: Coalition for Sonoran Desert Protection v. Federal Highway Administration (D. Ariz.)

On April 21, four conservation groups sued to stop the construction of a 280-mile long corridor for Interstate 11, including desert lands between between Saguaro National Park and Ironwood National Monument. According to the plaintiffs, the National Park Service, U.S. Bureau of Land Management, U.S. Forest Service, and U.S. Bureau of Reclamation raised concerns that the selected route would permanently and severely harm wildlife populations and public lands.

New lawsuit: State of Alaska v. United States of America (D. Alaska)

On April 26, the State of Alaska filed a complaint in the Alaska federal district court to quiet title regarding ownership of land under navigable waters and submerged lands in Alaska. The state is also issuing trespassing orders to federal agencies, including the Forest Service, with structures such as docks on such lands without state permits. This article includes a counter-argument.

New lawsuits: County of Ventura v. U. S. Forest Service (C.D. Cal.), City of Ojai v. U. S. Forest Service (C.D. Cal.), Los Padres Forestwatch (and 6 others) v. U. S. Forest Service (C.D. Cal.)

On April 27, three complaints were filed against the Reyes Peak Forest Health and Fuels Reduction Project in the Los Padres National Forest. Plaintiffs object to the use of a categorical exclusion from NEPA disclosure to approve the project. The Decision Memo states that trees between one inch and two feet in diameter will be “thinned.” Plaintiffs are also suing the United States Fish and Wildlife Service for violating the Endangered Species Act and the APA by falsely concluding that the project would not harm California condors and their critical habitat, and the Forest Service and Secretary of Agriculture for violating the HFRA and the APA by failing to issue annual reports pertaining to the use of categorical exclusions. The link above includes links to each of the complaints. This article includes more information about the project, and a link to the Decision Memo.

- Daniel Boone NF Red Bird Project

On April 28, Kentucky Heartwood filed a notice of intent to sue the U.S. Forest Service to protect endangered species in the South Red Bird Wildlife Enhancement Project on the Daniel Boone National Forest. The threatened or endangered species include snuffbox mussels, the Kentucky arrow darter and three bat species. The Forest Service says the purpose is to create more young forest habitat for deer, elk, grouse and turkey, and will leave behind seven to 20 trees per acre. There are also concerns about damage to and possible logging of large old trees (including potential damage to a “champion” red hickory), white oak regeneration (see our recent discussion here), landslides, and invasive species. Logging for game species at the expense of at-risk species came up here.

New lawsuit: Center for Biological Diversity v. U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service (D. D.C.)

On April 29, plaintiffs filed a complaint against the Fish and Wildlife Service and the Departments of Interior and Agriculture to seek documents under the Freedom of Information Act related to “communications within the federal agencies and with non-federal entities discussing changes or revisions to the regulatory requirements for programmatic consultations under Section 7 of the U.S. Endangered Species Act.” This concerns legislation proposed to codify currently temporary language that exempts the Forest Service from the requirement to reassess land-management plans after a species is listed or critical habitat is designated on the affected national forest. This resulted from the “Cottonwood” litigation, we discussed here.

A woman who accidentally dropped her cellphone into the hole of an outhouse in the Olympic National Forest, and fell in while trying to retrieve it, had to be rescued by firefighters.