NOTE: This post has been updated with information from Dan Farber of UC Berkeley Law. Thanks, Dan! I’ve added his thoughts in red below.

It’s a bit hard to keep track of what’s in the statutory amendments of last year and what’s in the new NEPA regs that Jon covered yesterday. I think this is a fascinating story that illustrates the confusion that can result when Congress and Admins mess around with the NEPA statute and regs..but this is only the tip of a future iceberg of glacial progress as the courts redo NEPA case law with the new NEPA regs. It reminds me a bit of the Paul Simon song:

Slip slidin’ away

Slip slidin’ away

You know the nearer your destination

The more you’re slip slidin’ away

The basic story of this case is that there is a request for a permit for exploratory drilling which will be completed in a year as per an existing CE. But the FS wanted them to do habitat restoration and monitoring, which would take longer. So they used the habitat restoration CE for that. Here are the details of the project according to Courthouse News:

Kore Mining Ltd. wants to drill 12 holes, 600 feet deep, to try to find gold on federally owned land — which is legal, so long as it applies for a permit. The federally owned land in question is, as Mueller describes it, “a wide and gently sloping expanse of 1,848 shrubby acres” pocked with hundreds of holes bored by mining companies in the 1980s and 1990s. At the time, technical limitations meant that those holes couldn’t go deeper than a few hundred feet. But Kore Mining believes there might be gold up in them there hills and that deeper drilling might be possible today.

Kore’s proposal would require clearing vegetation and building about a 1/3-mile temporary access roads. The U.S. Forest Service concluded in 2020 that the project “was unlikely to have any significant effects on the environment” since it would take less than a year and require less than a mile of new roads.

During the public comment period that followed, numerous environmental groups, nearby towns and government agencies objected to the project. Of particular concern was the bi-state sage grouse, an iconic bird famous for its extravagant mating dances — “Picture a spike-tailed, puff-chested small turkey in a brown tuxedo, shaking and strutting in the brush,” Mueller wrote.

The Forest Service then said it would not allow Kore Mining to undertake any “disturbance activity” between March and June, the sage grouse’s mating season. It also said Kore would have take a number of steps to restore the land after its exploratory drilling, including returning the land to its original slope and sowing native seeds. And a biologist would have to monitor the area for three years after the drilling stopped.

Four groups — the Center for Biological Diversity, the Western Watersheds Project, Friends of the Inyo, and the Sierra Club — filed a lawsuit in October 2021 against the U.S. Forest Service and Kore Mining to halt the project.

“This drilling project will cause exactly the kind of noise and commotion that make bi-state sage grouse abandon their habitat,” said Ileene Anderson, a senior scientist at the Center for Biological Diversity, in a statement at the time. “It’s appalling that the Forest Service is willing to push these beautiful dancing birds closer to extinction for a toxic mine.” Environmentalists also worried about the impact the drilling would have to the groundwater in the area that feeds into the Owens River, which supplies water for Los Angeles.

So basically, some groups don’t want the project. The court case seems to have focused on the two-CE issue;that is, they used two CEs instead of an EA.

Here’s what the Judge Mueller said about this when finding for this in March of 2023.

While the mining operation was covered under the second exception, the habitat restoration, and in particular the three-year monitoring period, would of course take longer than a year, and would those need to be covered by that first exception.

“It is undisputed that all drilling, grading and construction will finish within a year; Kore will regrade the pads and roads and cap its wells within a year; revegetation is a nonherbicidal wildlife improvement for sage grouse; and Kore will construct less than a mile of new access roads,” Mueller wrote. The question, then, was: “Can a project be approved in two or more parts, each covered by a different exclusion?”

Mueller decided yes — though it may not be ideal, “a patchwork of individually-insufficient-but-collectively-sufficient exclusions can cover a single project or action.” Or: “Zero plus zero is zero.”

I do think that restoration is a different kettle of fish than other CEs, the whole point is to improve the environment.

Now as Dan Farber of Berkeley Law said in an interesting post today, the (so-called) Fiscal Responsibility Act was signed in June 2023 (after the court decision), saying that

After the 2023 amendments, Section 111(1) of NEPA now defines a CE as “a category of actions that a Federal agency has determined normally does not significantly affect the quality of the human environment within the meaning of section.” And section 106(a)(2) says that an agency doesn’t need an environmental assessment “if the proposed agency action is excluded pursuant to one of the agency’s categorical exclusions.” It seems clear that the action — a combination of drilling and restoration — does not fit “one of the agency’s categorical exclusions.”

However, that was after Judge Mueller made her decision. So that changed the statutory landscape. Ah… but there was an appeal.

Dan says in his piece:

But what’s most striking isn’t what the court did discuss but what it didn’t mention : the fact that last year’s NEPA amendments speaks directly to one of those issues. Apparently the word that NEPA was extensively amended a year ago hasn’t yet reached the federal courts.

So I asked Dan whether the statutes and regs for the original decision applied, here’s his emailed response:

The general rule is that an appeals court applies the law as it exists at the time of the appeal. The NEPA amendments were effective immediately, and there’s no indication in the statute that they apply only to agency decisions occurring after the amendments. So the Ninth Circuit should have considered them (or at least given some reason for refusing to apply them). I don’t think that judges are really aware of the new law, to tell the truth, since they’re so used to operating in a setting where the statute itself is very vague and thinking all the rules come from the CEQ regs or the courts.

This is of concern (unless the goal of government is a full employment program for lawyers) for two reasons. Agencies can’t predict the future regulatory environment or future case law. Also the idea that judges aren’t aware of this law.. this seems problematic. Can lawyers make recommendations for topics for them to cover in their next training? Back to Dan’s original post.

The majority said that the agency’s justification for avoiding the NEPA process was wrong, and that refusing to do an environmental assessment was such a basic violation of NEPA that it could not be considered harmless. The dissent, on the other hand, says that the Forest Service had plainly taken as close a look at the environmental issues as it would have in an environmental assessment. (If that’s true, one wonders, why didn’t the Service just do an environmental assessment in the first place?) For that reason, the dissent argues, any procedural error by the agency was harmless.

********

This is an example of why Forest Service people sometimes think “litigation is a crapshoot”, as my colleague JR was known to say. From a Sierra Club piece:

The Court held that “The Forest Service asks us to adopt a view of categorical exclusions that will swallow the protections of NEPA. We decline to do such violence to NEPA’s procedural safeguards.” (Court decision at p. 25). As the Court explained: “when an agency applies CEs in a way that circumvents NEPA’s procedural requirements and renders the environmental impact of a proposed action unknown, the purpose of the exclusions is undermined. That is the case here.” (Court decision at p. 24).

Just think about it.. Judge A says “0 plus 0 equals zero”; I say restoration is by definition positive, so the sum is >0, and the Appeals judges- I think do a bit of over-hyping (is that their usual kind of language?)- “do violence to NEPA’s procedural safeguards,””swallowing the protections”- I’d argue that using the restoration CE might regurgitate a protection or two.

Do they think Mueller was “doing violence” by agreeing with the FS? Or was she just “promoting” violence?

Anyway, back to Farber’s piece:

The dissent doesn’t have a bad argument, but there are some differences between what the agency did and the environmental assessment process that could be significant. The Service did solicit public input, but the regulations governing environmental assessments require fuller opportunities to participate. Instead, “agencies shall involve the public, State, Tribal, and local governments, relevant agencies, and any applicants, to the extent practicable in preparing environmental assessments.” Asking the public whether it agrees with use of a CE isn’t the same as involving them along with governments at all levels in the preparing an assessment.

Yet according to the Courthouse News article,

During the public comment period that followed, numerous environmental groups, nearby towns and government agencies objected to the project.

It sounds like the public involvement process was similar to that of an EA in that respect (without looking at the documents). Here’s what Dan brought up in his email:

In terms of the harmless error doctrine, the idea is that you violated the proper procedure but that it didn’t affect the outcome — no harm, no foul. The question I raised is whether we can be sure of that. In response to one of your other questions, we do know (as I said in the post) that there were a lot of comments filed. But were they as detailed as the commenters would have offered in an environmental assessment? After all, they were really only designed to get the Forest Service to agree to at least consider the environmental consequences rather than doing a categorical exclusion. If there had done an environmental assessment, would the state or federal fish & wildlife people have been consulted?

That’s a really interesting take. Every CE public comments I’ve read (that being, when people don’t like the project) have been more general than “does this CE fit”? I’ve appended the summary of the response to comments below.

In fact, the agency did originally say an environmental assessment was needed, but the company complained and the agency quickly reversed itself. (Is it a coincidence that this was the Trump Administration?) Maybe the agency should have stuck with its original position rather than shortcutting the process in its haste to approve the mining project.

Remember the 9th Circuit judge (appointed by Obama) agreed with the FS that it was a legitimate approach. I’m calling “unnecessary invoking of Trump” here.

In addition, an environmental assessment would have required a Finding of No Significant Impact (FONSI), which would also have had to discuss alternatives to the proposal. None of the judges cites any discussion of alternatives by the agency. We don’t know if there were other, less sensitive, locations that might have been used. If there had been an environmental assessment, the agency would have had to discuss that.

This is exploration.. not a final plan. It could well not be economic to extract there or there might not be any gold. It makes sense to me to look at alternatives when an actual mine is proposed. Exploration to me is mostly collecting information that is useful in preparing environmental documents and .. there is a CE for that.

***********

I think this illustrates a couple of things.. how judges can disagree, how some of them might not be able to keep up with NEPA at this point in time. My own experience with industry is that they did not want us to use available CEs because if it’s going to be litigated, then there’s better documentation and it’s safer. Or so the timber industry individual said, and so our OGC folks told us. If it hadn’t been for the appeal, the two CEs would have worked.

I also think Dan’s comment here is of interest, when do the facts of the case matter, and when is the idea that applying the law to this case would lead to some kind of generic CE-piling

In terms of piling up CEs, if the Forest Service’s theory was right, it wouldn’t just apply to this case. It could potentially give agencies the power to use a bunch of CEs, shortcut the normal procedures for environmental assessment, and then claim that even though they didn’t used the required process, it was all o.k. in the end.

But of course all this is moot with the new amendments to NEPA.

You may be right that this is a situation where there couldn’t possibly have been an environmental impact, but then you wonder why there was so much opposition from the Sierra Club and others.

My experience is that slowing a project, step by laborious legal step, is a strategy to stopping it. I’d guess that this isn’t about the exploratory wells at all but about making an inhospitable environment for the developers. I doubt that if the FS does an EA, that there will be no further litigation. The company can look uphill to possible litigation on the EA, an EIS for the mine, litigation, appeal court rulings, and so on. Maybe the next Admin will refuse to defend the FS for some reason, who knows? With current interest rates, this degree of uncertainty would make companies (and investors) wary.

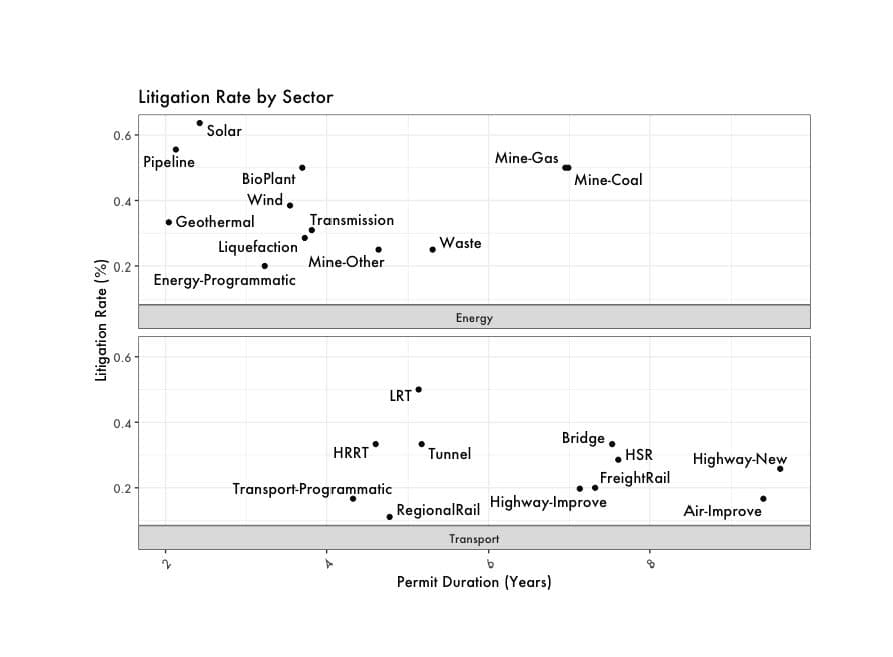

If we project this onto renewable energy projects, solar, wind and transmission may be better off because there is no exploratory stage, as with geothermal. Anything mining related will have trouble, I predict, even strategic minerals.

*******************************

Here’s the response to comments:

PUBLIC INVOLVEMENT

This action was originally listed as a proposal on the Inyo National Forest Schedule of Proposed Actions (SOPA) and updated periodically during the analysis. The project was first published in the SOPA on January 1, 2021. Public scoping was opened on April 8, 2021 and closed on May 13, 2021, which included a one-week extension of the original scoping period. Scoping letters were mailed to one address and electronic delivery was made to another 37 project subscribers through GovDelivery. Comments were collected online in the Comment Analysis and Response Application as well as through hardcopy, and email. In response to public requests, the Responsible Official decided to extent the scoping period by one week, and notified the public with a news release and email to the original email list.

The comments received expressed concerns on a number of subjects that included potential impacts to tourism, wildlife, cultural resources, water quality and recreation which was primarily about the fishery on Hot Creek. Comments also addressed geothermal and seismic activity, air quality, noise and light pollution. Technical studies completed in response to comments include KORE Long Valley Exploration Sage‐Grouse Lek Baseline Noise Monitoring and Drilling Noise Analysis; and Hydrogeologic Evaluation. Additional project design features and/or mitigations measures were also added to the plan of operation. These include:

• Sound barriers for equipment to reduce noise that might affect sage grouse.

• Shielded and directed lighting to limit potential light pollution.

• Air quality permits, if required, to be obtained through the Great Basin Air Quality

Management District

• Operator is responsible for immediate repairs of any, and all damages to roads, structures,

and improvements, which result from the operations.

• Noxious weeds will be controlled.

Most of the public comments associated this exploration drilling project with the development of a long-term open pit mine and processing facility, which has not been proposed. The purpose of a mineral exploration project is to assess the potential for mineral concentration at a volume that would be economically feasible to produce and does not automatically lead to an actual mine. An application has not been submitted or proposed for a mineral extraction project and if that were to occur, that application would be processed as a separate project.