This proposed bill language of the current bill would affect the FS and BLM with regard to certain projects (not of the veg management persuasion). The link takes you to the full bill, the the section by section, and a summary of the changes.

**************

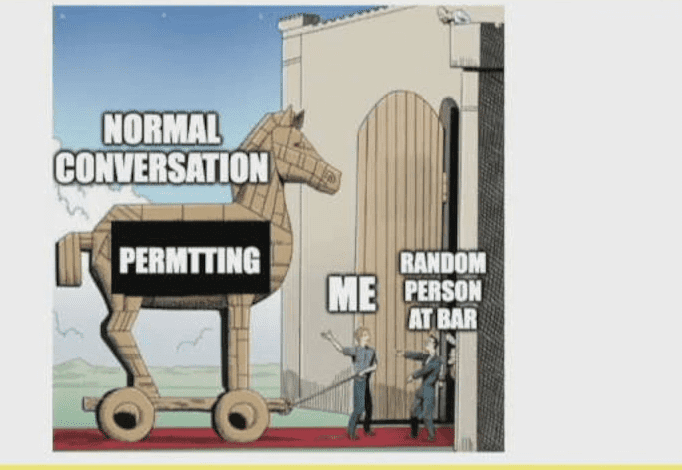

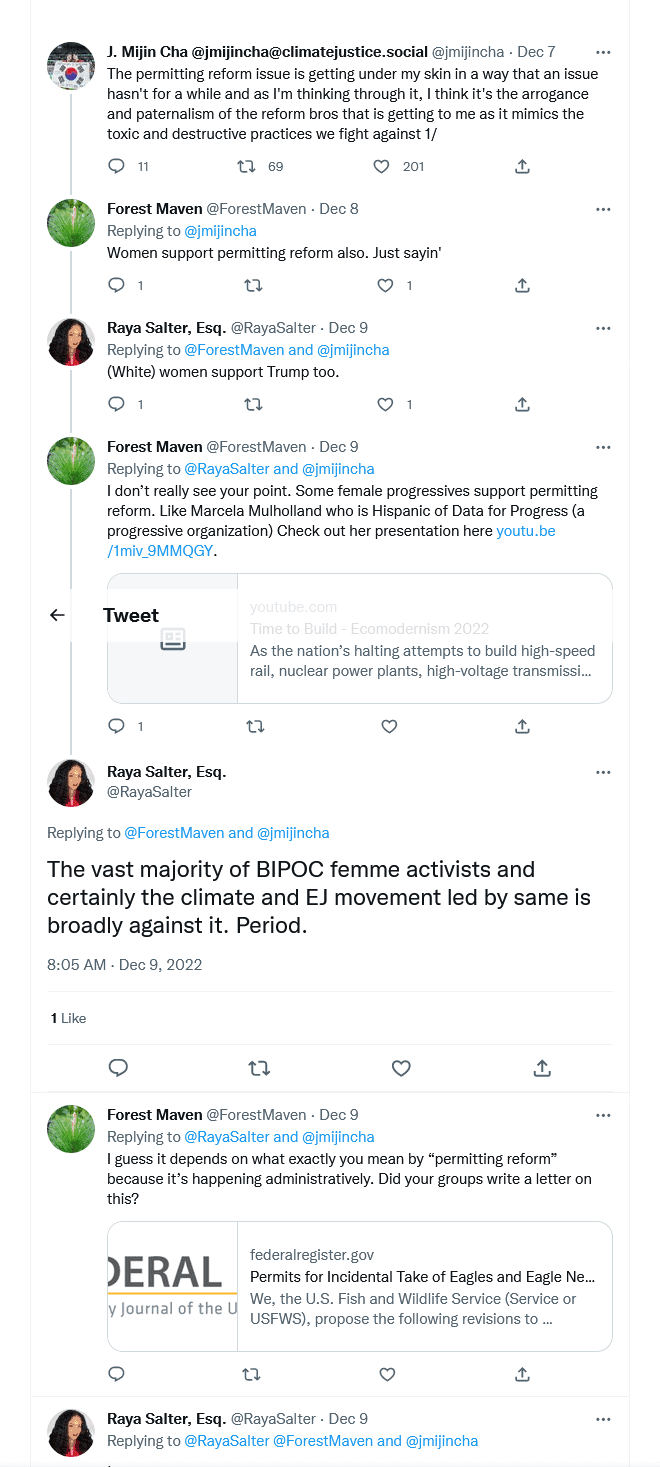

Sidenote: The permitting reform discourse, as opposed to the permitting reform bill. As Marcela Mulholland of Data for Progress pointed out at the Breakthrough Institute conference that I posted about here, the (at least “progressive”) discourse around permitting reform is not very productive. It’s like the concept itself is wrong (everything is currently perfect), which seems kind of irrational. What human, let alone government, activity, can’t be improved? Why is the concept, as opposed to the reality, such a flashpoint? A person, apparently on the New York State Climate Action Council, and I had a discussion on Twitter that reflects this.. I actually thought it was kind of funny.

*****************************************

Oh, and I thought this op-ed on the Hill by Catherine Wolfram “Progressives should have supported Manchin’s permitting reforms: Here’s why” had some good points.

Indeed, the arguments that the progressives make against carbon pricing are exactly why they should have supported Manchin’s permitting reforms. Blocking fossil fuel projects makes it more costly to deliver energy with existing fossil fuels. In effect, it creates a kind of carbon price, just one that’s haphazardly applied, usually extremely high, and where the revenues accrue to fossil fuel producers instead of the government. At the end of the day, low-income households’ energy bills go up.

*****************************************

But let’s move on to what’s specifically in the bill.

Projects are defined as “those projects for the construction of infrastructure to develop, produce, generate, store, transport, or distribute energy; to capture, remove, transport, or store carbon dioxide; or to mine, extract, beneficiate, or

process minerals which also require the preparation of an environmental document under the NEPA and an agency authorization, such as a permit, license or other approval.

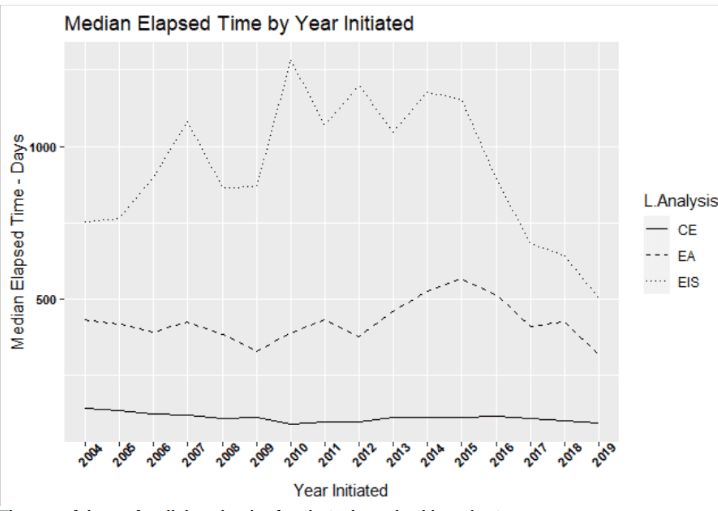

It seems to me as if it’s mostly speeding up things (documents and disagreements and litigation) that can otherwise languish (and don’t we know it…). That’s what it says in the summary.

WHAT THE BILL DOES: Accelerate, not bypass. The bill will accelerate permitting of all types of American energy and mineral infrastructure needed to achieve energy security and climate objectives, without bypassing environmental laws or community input.

Here was the one I thought will be interesting to observe (if this passes):

Sec. xx15. Litigation Transparency

Topline Summary:

• Requires public reporting and a public comment opportunity on consent decrees and settlement agreements seeking to compel agency action affecting energy and natural resources projects.Detailed Summary:

• Subsection (a) defines civil actions, consent decrees, and settlement agreements covered under this section.

• Subsection (b) requires that agencies publish online the notice of intent to sue and the complaint in a covered civil action not later than 15 days after receiving service. The subsection also requires agencies seeking to enter into a covered consent decree or settlement to publish online the proposed consent decree or settlement and provide an opportunity for public comment not later than 30 days before filing the consent decree or settlement with a court.

• Subsection (c) requires an agency to consider public comments received on a proposed consent decree or settlement agreement under subsection (b) and authorizes agencies to withdraw or withhold consent if the comments disclose facts or considerations that indicate that the agency’s consent is inappropriate, improper, inadequate, or inconsistent with any provision of law.

What do you all think about this, and about other parts of the bill?