I have made several comments recently about situations that should not trigger NEPA procedures because they do not have adverse effects on the physical environment. I became interested in this topic in 1986 when I noticed that development interests were arguing that forest plans adversely affected “community stability” (a euphemism for social and economic impacts), and this was being addressed as an “environmental” impact in NEPA documents. Given that the goal of NEPA was better environmental protection, I could see how inferring that social and economic impacts of protecting the environment must be addressed through a NEPA process could lead to less environmental protection.

As an example of that actually happening, let’s talk about the proposal to conserve 30% of the nation’s lands (America the Beautiful/30 x 30).

Property rights advocate Margaret Byfield’s strategy for defeating the Biden administration’s aggressive conservation pledge comes with a twist: She wants landowners to embrace the nation’s bedrock environmental law.

Byfield, the executive director of American Stewards of Liberty — and daughter of the late E. Wayne Hage, an icon of the Sagebrush Rebellion II movement — sees the National Environmental Policy Act as a cudgel in her campaign to upend the “America the Beautiful” program.

But Byfield emphasized Friday that the strategy must also embrace NEPA, arguing the Biden administration has skirted its responsibility to execute “a programmatic” environmental review of its “America the Beautiful” plan.

“This is the environmentalists’ great law that they use as a weapon against productive agriculture and actually any kind of project,” Byfield said. “They use it to slow down and stop projects, they use it as a weapon.”

Byfield asserted that the Biden administration has skirted NEPA by moving forward without an environmental review.

“They also know if they do NEPA right, it’s going to take them three, maybe six, maybe nine, maybe 10 years to complete the study the way they make us do it. So why aren’t they living under the same laws they force us to follow?” she asked.

The obvious reason is that NEPA was not passed by Congress to protect “agriculture and actually any kind of project.” The ASL seeks to turn NEPA on its head. The interesting thing is that the Center for Biological Diversity did not mention this, instead stating that the President and executive orders are exempt from NEPA, and actually inferred that the future site-specific conservation actions could require NEPA procedures.

The law regarding application of NEPA to non-environmental consequences of environmental protection measures is less clear than it should be. The Supreme Court framed this question in Metropolitan Edison Co. v. People Against Nuclear Energy in 1983

But we think the context of the statute shows that Congress was talking about the physical environment — the world around us, so to speak. NEPA was designed to promote human welfare by alerting governmental actors to the effect of their proposed actions on the physical environment.

But, here’s a confusing discussion by the Ninth Circuit in the 2000 case of Kootenai Tribe of Idaho v. Veneman, which challenged the procedures used to adopt the Forest Service’s Roadless Area Conservation Act (the “Roadless Rule”). (Other plaintiffs in this case were Boise Cascade Corporation, motorized recreation groups, livestock companies, and two Idaho counties.) The Forest Service did not appeal the district court’s injunction of the Roadless Rule, but an appeal was filed by environmental intervenors, who argued that the Rule did not alter the natural physical environment and require an EIS under NEPA.

Under NEPA, a federal agency is required to prepare an EIS for all “major Federal actions significantly affecting the quality of the human environment.” 42 U.S.C. § 4332(2)(C) (emphasis added). “Human environment,” in turn, is defined in NEPA’s implementing regulations as “the natural and physical environment and the relationship of people with that environment.” 40 C.F.R. § 1508.14. See also Wetlands, 222 F.3d at 1105. The dispositive issue here is whether the Roadless Rule sufficiently affected the quality of the human environment to trigger the procedural requirements of NEPA.

We have explained that NEPA procedures do not apply to federal actions that maintain the environmental status quo. See Burbank Anti-Noise Group v. Goldschmidt, 623 F.2d 115, 116-17 (9th Cir.1981) (NEPA does not apply when an agency financed the purchase of an airport already built); Nat’l Wildlife Fed’n v. Espy, 45 F.3d 1337, 1343-1344 (9th Cir. 1995) (NEPA does not apply when agency transferred title to wetlands already used for grazing); Bicycle Trails Council of Marin v. Babbitt, 82 F.3d 1445, 1446 (9th Cir.1996) (closure of bicycle trails does not trigger EIS). In other words, “an EIS is not required in order to leave nature alone.” Douglas County, 48 F.3d at 1505 (citation and internal quotation marks omitted). The touchstone of the EIS requirement is whether the change in the status quo is “effected by humans.” Id. at 1506.

Because human intervention, in the form of forest management, has been part of the fabric of our national forests for so long, we conclude that, in the context of this unusual case, the reduction in human intervention that would result from the Roadless Rule actually does alter the environmental status quo.

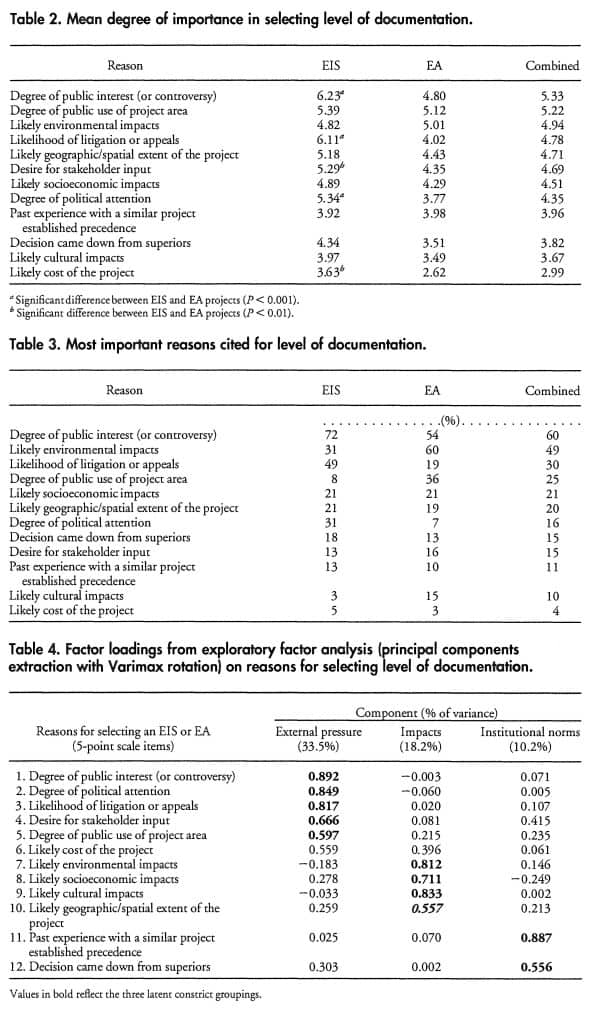

This perverse rationale (for this “unusual” case) has no citations, and I think it is only justified by a desire to decide the case on the merits of the EIS (which it upheld) rather than on a procedural question. Moreover, it ignores the additional requirement that the environmental status quo must be adversely affected (the term “adverse” is used many times in the CEQ NEPA regulations). Here is a 2012 paper on “beneficial effects” under NEPA. Its conclusion echoes my concern from 35 years ago (which has become a reality).

Third, the policies underlying NEPA are in tension with a Beneficial Impact EIS requirement. Such a requirement would produce unnecessary cost and delay for environmentally beneficial projects and create perverse incentives for federal agencies without any compensating informational benefits.

Agencies that are using NEPA to justify delaying environmental protection are probably not violating the words of NEPA, but clearly violate its spirit. Moreover, anti-environmental plaintiffs should not be able use the courts to facilitate this violation.