Martin Nie helpfully pointed me to the text of his letter on the Holland Lake project. What’s interesting about this, to me, in light of the decision, is how this highlights the role of environmental analysis compared to public engagement. Some folks seem to like to lump them together (not Martin).. “with a CE the public won’t be involved” but this particular CE had public meetings and obviously a comment period (evidence- this letter, among others). And whether the FS uses the CE when this decision comes back around, I would expect them to do the same kind of public involvement.

Here’s a link to Martin’s letter , and here is a link to the scoping document. Lots of interesting stuff in there, including upgrading water and sewer, and clarifies the Forest Plan direction for the area.

Increased use is also occurring at the adjacent USFS East Holland Lake Connector Trailhead. This increase in use is creating a situation in which users park along the Holland Lake Road because there is no longer room in the existing trailhead parking area. Additionally, the existing vault toilet is no longer adequate to handle the amount of use it experiences. This situation may be causing additional resource concerns as users find alternative options*. Improvements at the Holland Lake Lodge and the East Holland Lake Connector Trailhead would offer the opportunity to satisfy some of the increased demand for outdoor recreation on public lands in the Swan and Flathead Valleys (Figure 2 & Figure 3). Holland Lake is identified by the Flathead National Forest Land Management Plan as a Management Area 7 – Focused Recreation (USDA 2018). The improvements proposed at Holland Lake Lodge align with recreation uses permitted in Management Area 7. Focused Recreation Areas typically include public recreation areas at or near a lake, large campground, developed ski area or year-round resort. Recreation in these areas is already occurring and is often enhanced by further development to increase public access and benefit local economies.

*Hmm. I wonder about the exact nature of these “alternative options,”; perhaps not best left to the imagination.

Here’s what Martin said about the Plan:

So much time, energy and resources collectively spent on revising this Plan, one of the first to be revised under the 2012 Forest Planning Regulations-Regulations that require the use of best available scientific information, public participation, and an “all lands” approach to National Forest management. So much work and money spent on the Montana Legacy Project, so carefully done so to protect the ecological and rural community values so cherished in the region. So much effort to protect the ecological integrity and feel of a special place. And yet none of that work seems to have shaped or informed a proposal that would undermine it all.

The agency’s purpose and need for action statement references the revised Forest Plan’s desired conditions for Management Area 7, Focused Recreation. This vague and discretionary plan component calls for providing “sustainable recreational opportunities and settings that respond to increasing recreation demand.” But this provision does not call for generating greater demand for even more intensive recreation nor can it be understood in isolation from other relevant parts of the Revised Plan, including the plan components for the Swan Valley Geographic Area, and requirements under 36 C.F.R. §219.9 “to contribute to the recovery of federally listed threatened and endangered species, conserve proposed and candidate species, and to maintain a viable population of each species of conservation concern.”

The special use permit and proposed expansion of Holland Lake Lodge is clearly and directly related to forthcoming activities and an environmental footprint that will extend far beyond the 15 acre permitted area. The type of intensive year-round recreation associated with the POWDR corporation makes this clear and is entirely inappropriate in an area so ecologically significant. The NEPA case law forbids the segmentation of related actions and requires that the cumulative effects of related actions must be considered, usually in an EIS. The Council on Environmental Quality (CEQ) also states that “federal agencies must be sure the proposed [CE] captures the entire proposed action” and “should not be established or used for a segment or interdependent part of a larger proposed action.”

It seems to me that this argument could be made for any project that has a appropriate CE. Perhaps all fuel treatment projects on the Forest could be characterized as “related actions” despite the existence of legislated and regulatory CEs. And it can be argued that anything is in some sense a “related action.”

I also question this claim :”The type of intensive year-round recreation associated with the POWDR corporation makes this clear and is entirely inappropriate in an area so ecologically significant.” With my experience with ski area expansion, every area is “ecologically significant” to someone; and these ski areas have opened to year-round recreation. To my mind, you’d have to tie a specific time of use to a specific environmental impact.

Since Martin is the Director of the Bolle Center (although he writes this letter in a personal capacity), I guess it was natural to bring up the Bolle Report from 1970 (52 years ago). For non-Montanans who have dealt with other permitted recreation expansions (in my case, ski areas) it seems a bit of a stretch, but OK.

Here we are, decades after the Bitterroot controversy, only to find local citizens and the public once again treated as antagonists, with a proposal to exclude them from a fully informed, scientifically credible, and participatory NEPA process.

Of course, development at Holland Lake is no Bitterroot controversy in terms of scope, scale and implications. But both cases signify something far bigger within the agency and Montanans clearly recognize something is once again amiss. Rarely have I been approached by so many citizens about a local project or proposal, all with deep concerns and lots of questions about the proposed expansion and the Forest Service’s misuse of NEPA. (my italics)

If you don’t agree with certain members of the public, are you “treating them as antagonists”? Despite public meetings, comment periods, etc.? And if the decision, as in this case, goes with those members of the public, are you still “treating them as antagonists”? Is it the process, the feelings of some (which ones?) or the decision itself the location for these antagonistic expressions?

Now is where the letter gets interesting:

To categorically exclude some projects and activities from full environmental review is both reasonable and necessary. Doing so can help the agency focus on proposed actions most likely to actually have significant environmental effects. But the USFS is now using its growing list of “CE” authorities to an alarming degree. Roughly 84 percent of the agency’s NEPA work is now done using CE determinations. The Forest Service seems intent on excluding even more projects and actions from NEPA review in the future, using new exemptions provided in the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law (BIL), among several other new authorities granted by Congress, and more controversially by the agency itself.

But to abuse this tool is to risk the agency’s credibility and social license. The intention to categorically exclude such a significant action sends a message that CEs are being used not as a way to do NEPA more efficiently, or to make better decisions-which is the whole point of NEPA-but rather a way to avoid the use of best available science and informed public participation in public lands management. The backlash is already evident and I’m afraid it will taint future good faith efforts aimed at actually improving the USFS’s implementation of NEPA.

In my old job in NEPA in DC, we’d see real CE abuse.. and this is not it. IMHO.

The Forest Service “seems intent” on following statutes legislated by Congress.. I certainly hope so! And why would the CEs in the BIL be less controversial than those developed by the agency (or Agency)?

I guess I just don’t see the logic path from “many people in the area and elsewhere don’t want more people at this 15 acre (based on Martin’s letter) permitted developed recreation site .” and (implied) the Forest Service “is intent on” “even more projects and actions from NEPA review”.

By the way, I took a brief scan of the Flathead Current and Recent Projects, specifically Under Analysis and Analysis Completed. It looks to me as if all the vegetation management and fuels projects are EISs or EAs. Perhaps the problem with CEs is the FS uses too many of them for common decisions like Ultra-Marathons? Or bike races (if Andy is reading this far).

We’ve also had a good discussion of CEs and their use in the previous post’s comments.

****************

And for the even more NEPA-nerdy..

As to the percentages of CE’s, it turns out that Martin used what is in this 2020 NEPA regulation :

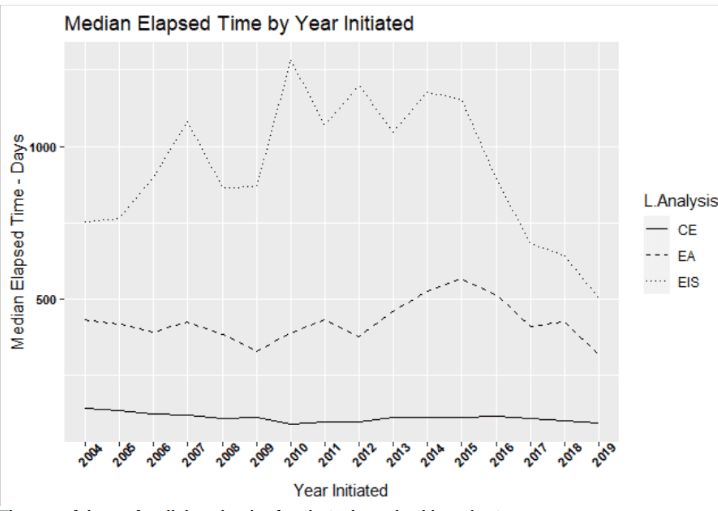

The Agency devotes considerable financial and personnel resources to NEPA analyses and documentation, completing on average 1,588 categorical exclusion (CE) determinations, 266 environmental assessments (EAs), and 39 environmental impact statements (EISs) annually (based on Fiscal Years 2014-2019).

The Fleischmann et al. (2020) estimate of CE% was for 2005-2018 and came up with 82.3 % CEs, and the FS estimate 84%, is from 2014-2019. We might expect that if the FS’s intention were to use more CEs, and it was busy generating administrative ones and the Congress was busy legislating CEs, since 2015 we would see more of an increase over that time period. The averages actually seem pretty invariant over those time periods.