I think it’s always interesting when you find yourself agreeing with someone whose background seems quite different from your own. I ran across this piece from a law professor at U.C Berkeley named Ethan Elkind (it was posted to an information source called Legal Planet, which I intermittently read) . What’s interesting to me is that he raises some of the same points on phasing out oil and gas production in California that are similar to phasing out on federal lands, as per Candidate Biden.

What I think is interesting about Elkind’s piece is that it echoes similar complexities of stopping production of anything, anywhere as long as the demand continues. This isn’t really rocket science to anyone who remembers the Timber Wars. Have we stopped using wood.. well…er.. no. We just get it from somewhere else. Which in the case of wood, appears to be working out just fine. Thank you, Canadians!

So here’s that argument from him (1) You’ ll Get it from somewhere if you have demand:

The challenge is that demand for fossil fuels in the state will remain for the foreseeable future, even if local production ceases. If we stop producing oil here, we’ll start importing more from elsewhere.

While California’s oil demand is already decreasing due to market and policy factors, until consumers completely transition to zero-emission vehicles and find alternatives to petroleum-based products like plastic and asphalt — and until refineries in the state stop exporting to markets around the Pacific — the supply will still find its way to the state. If that oil comes from out-of-state sources, the carbon footprint may even be higher than if California produced it domestically, due to shipping emissions.

(2) Here’s the economic argument:

However, economic theory indicates that a decrease in California production will mean some decrease in consumption, as global prices will rise slightly from reduced overall supply. One study indicated it could lead to global emission reductions of 8 to 24 million tons of CO2 per year. And any oil left in the ground is oil not burned in the long run, meeting one of the highest priorities of climate activists. So a California phase-out could help avoid some emissions, though the rate is unclear.

How is demand reduced in this case? Via higher prices. Since buying gasoline, heating oil, and natural gas is necessary for folks, it seems like this price rise could have unintended consequences of falling unfairly on poorer people who can’t afford to buy new electric cars and appliances, and who have to drive to work and heat their homes.

(3) The “leadership” argument:

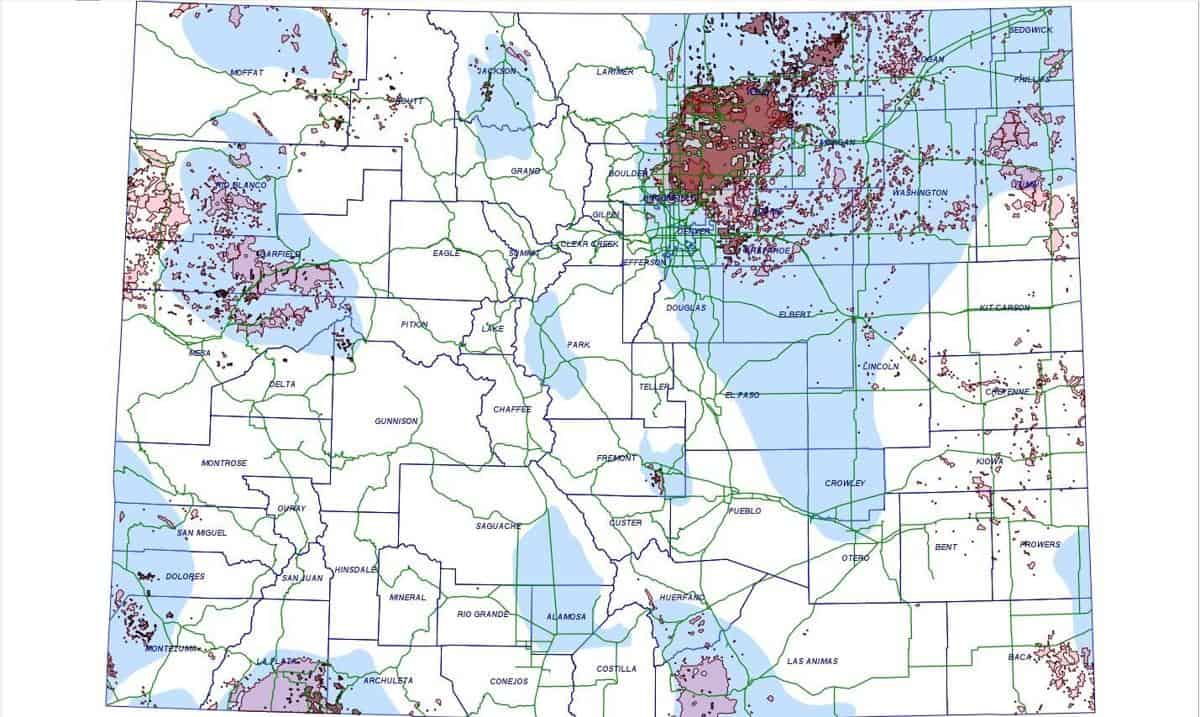

What about the political implications of phasing out oil and gas consumption for climate policy? One argument is that a phase-out here might inspire other jurisdictions to follow suit. As most climate models indicate that some percentage of fossil fuels will have to remain untapped as an imperative for avoiding the worst impacts of climate change, why not start in California, a state committed to climate action? It might be hard to imagine that top oil-producing countries like Saudi Arabia, Iraq and Iran (or other U.S. states) would be so inspired, but perhaps places like Norway or Colorado might be more politically open to it. And if the oil industry in California phased out, its lobbying power might also wane, allowing the state to pursue more aggressive policies on the demand side.

I don’t think this applies to federal lands. And FWIW, I’m not a political writer, but from where I sit, wanting to be “more like California” is not likely to be a winning slogan in Colorado.

(4) Reducing supply: potentially enriching the “bad guys”. These include corporations and countries of questionable dependability or friendliness. This is generally thought of as an international security issue. Gas lines from the 70’s are fading from public memory, but older people remember.

The economic impacts of a phase-out for climate policy are also complicated. As Severin Borenstein at UC Berkeley Energy Institute at Haas blogged in 2018, a phase-out in California would mean slightly higher worldwide oil prices, which would in turn enrich the major oil producing companies and countries who are still providing supply. As he summarized:

One could think of this as similar to a very small worldwide carbon tax, except in this case the revenue is not rebated to the population as a whole or used to reduce other taxes, but rather handed to those who own and control the world’s oil production.

(5) Oil and gas wells don’t belong in close proximity to communities.

But there is one clear benefit from phasing out in-state oil and gas production in California: improved health and safety of surrounding communities. Scientists have linked drilling for oil and gas to numerous public health challenges, including increased rates of asthma, cancer, and other health threats. And much of the drilling in California occurs in or near residents of disadvantaged communities, adding to the urgency.Also

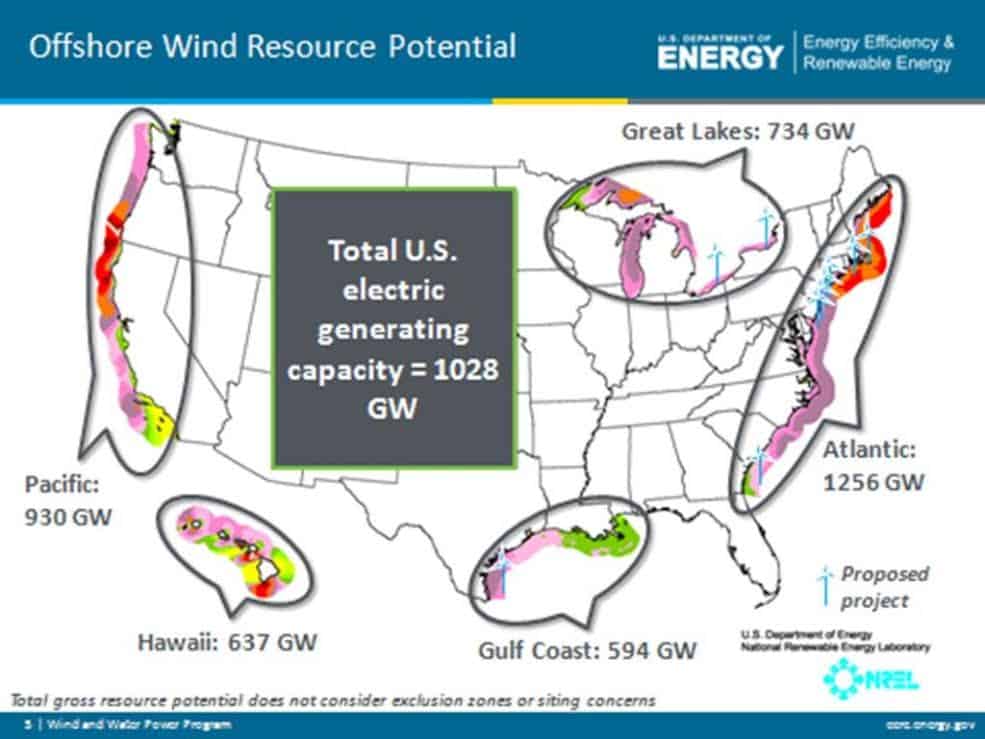

(Note: in Colorado this has been studied extensively, and the health impacts are not that straightforward. It’s also not clear how much in Colorado is near residents of disadvantaged communities. Also, if you switch from oil and gas rigs to wind turbines, there can be health impacts on neighbors as well, but more than likely, they are not the same neighbors.)

So if we read through all this, a person could come to the conclusion that oil and gas drilling should be kept away from communities. What place better, then, than federal lands?

*************************************************

What I think Elkind may have missed.

(6) this piece doesn’t mention the impacts of California losing direct and indirect taxes and royalties from O&G production. Perhaps they are such a big, rich state it doesn’t matter. For example, New Mexico is the 50th poorest state (according to Wikipedia). The state gets half of federal O&G royalties. According to this handy BLM website that shows disbursements, New Mexico received $1,165,963,636 in 2019.

(7) Jobs I’m agnostic on how this will work out. The idea is for O&G workers to transition neatly into renewable energy jobs, but we don’t have any idea how that would work in practice. I’m willing to think it could be done (have the same number of the same-paying jobs), but it seems to me that this would depend on the job market and economy as a whole. On the other hand, O&G has always been a volatile industry, and in fact people are getting laid off now due to prices. In fact that’s how former Governor Hickenlooper (currently a Senate candidate) started out, as a petroleum geologist and the craft beer industry and Colorado would be poorer if he hadn’t transitioned. On the third hand, different people and different social classes may have different levels of resilience.

(8) Environmental pros and cons of getting it from elsewhere (as in, is their production more environmentally friendly, with regard to methane emissions or ??) other than the transportation-related emissions, which he did mention.

These are all very thoughtful arguments, so thank you Professor Elkind for rounding these up!