Side note: whatever your thoughts, please comment on the MOG ANPR here. That is Mature and Old Growth Advanced Notice of Proposed Rulemaking. Some people have had trouble finding the link, perhaps due to the bizarre title “Organization, Functions, and Procedures; Functions and Procedures; Forest Service Functions.” Comments are due June 20th. We appear to be in the middle of a major media campaign on the MOG, so this seems like a good time to discuss some concepts.

Norm Christenson and Jerry Franklin had a an op-ed in Politico yesterday. I’m a big Jerry Franklin fan, based on my personal interactions with him since the 80’s. I’ve told some of the stories before, so I won’t bore you with them again. Mostly our disagreements have been about west-side vs. east-side practices, ecology and experience.

I like how they tagged on the wildfires in Canada to “underscore the need to let our current mature forest grow old.” You could also argue that the wildfires in Canada underscore the fact that wildfires are a danger when trying to use forests to mitigate climate change. Because if you believe that climate change will cause forests not to grow back, you’ve just blown your last tree sequestration opportunity plus released much carbon (and PM2.5).

“It turns out the age and composition of forests makes a big difference in what role they play in preventing wildfires and storing carbon. Old growth forest is the best at both, but there is very little old growth left in either the western or eastern United States.”

I would argue that old growth forest in some species/places is not the best in “preventing” wildfires (what does “preventing” even mean in this context?). Take a mixed ponderosa/true fir understory stand with large old pp.. how exactly does that “prevent” wildfires? I won’t go into carbon because the sequestering/storage burning up all depends on assumptions which may differ.

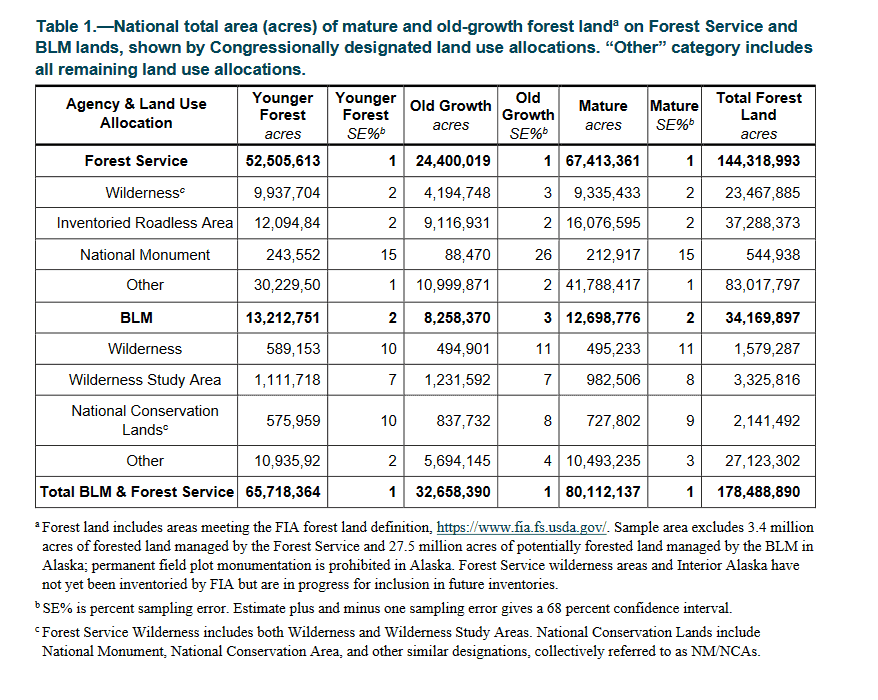

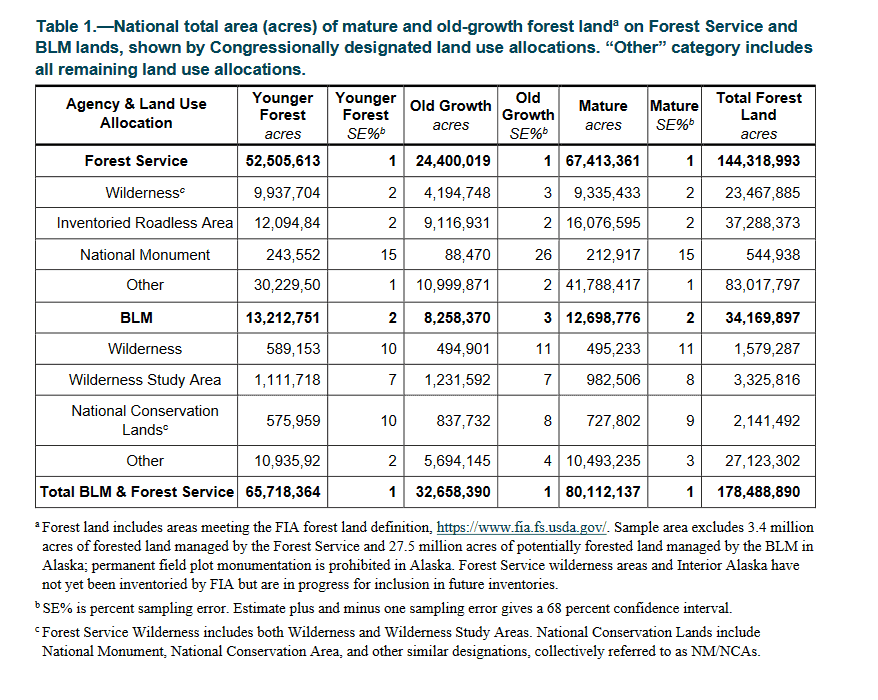

As part of the MOG effort, the FS counted the BLM and FS Old Growth acres and you can see them in the above table. It looks like 33 mill acres or thereabouts, or about 18% of the total. Note that this is just FS and BLM, there is probably OG on other state and country and private lands as well. So.. are 33 ish mill acres plus other unknown acres “very little” or not? How would we know what the “right” amount is?

But a large amount of the forests on public lands is what foresters call “mature” forest, which is nearly as good as old growth and in fact is on the brink of becoming old growth. It is these older forests that will help us prevent future forest fires and will do the most to reduce climate change, and its these forests that we need to protect at all costs.

I’m still interested in the mechanism of older forests helping us “prevent” fires. I have to admit, the old forests in my neck of the wood seem to be slacking off on this.

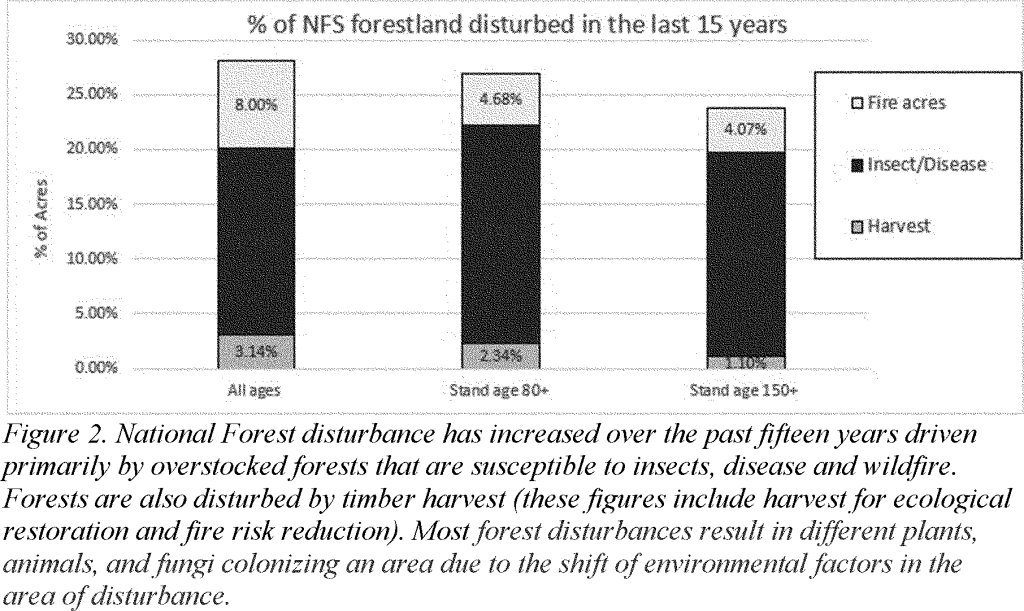

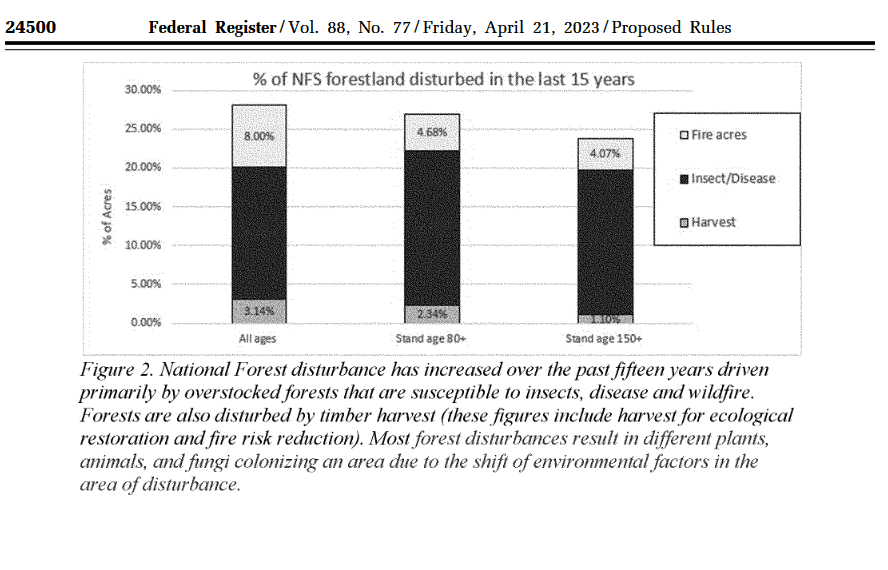

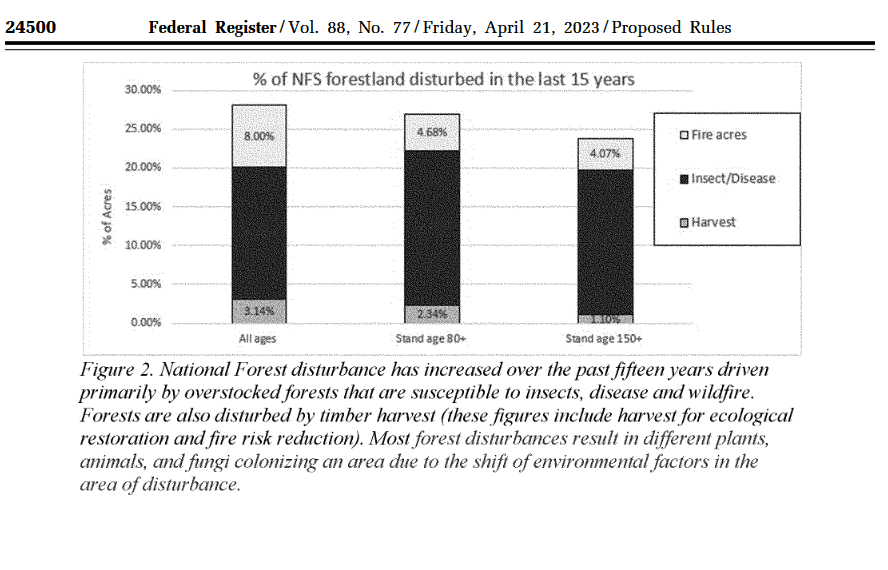

Then there’s the “p” word.. protect- the question is “protect from what?” This op-ed seems to mean “protect from removing any trees”.. but you can in the chart below (in the ANPR) see the timber harvest acres (including ecological restoration and fire risk reduction) are relatively tiny compared to fire and bugs and diseases. I guess I can see the argument “we can’t affect wildfire, and insects and diseases, so let’s focus on timber”; except that we can affect acres impacted by wildfire by thinning. Unless you believe that fuel treatments, PODs, etc. don’t help protect mature and older forests. Which isn’t the view of the fire science community nor practitioners. In fact, that isn’t addressed in this op-ed.

Within a few years, tree seedlings grow quickly, and their canopies expand to form a continuous green “solar panel.” The time it takes for this growth depends on the site’s fertility and the number of pioneer trees in the environment. The result is an immature forest composed of trees of small stature and similar age. These immature forests pose a high risk of wildfire due to the abundance of fine fuel, small branches and leaves, near the ground.

Within a few years, tree seedlings grow quickly, and their canopies expand to form a continuous green “solar panel.” The time it takes for this growth depends on the site’s fertility and the number of pioneer trees in the environment. The result is an immature forest composed of trees of small stature and similar age. These immature forests pose a high risk of wildfire due to the abundance of fine fuel, small branches and leaves, near the ground.

This reminds me of our 1980’s Central Oregon silviculture workshop with Bruce Larsen and Chad Oliver- when trees compete for water, they don’t grow the same way as the standard models and thinking based on competition for light. The old mesic forest bias. And when water is limiting, then thinning can increase vigor of trees and reduce beetle outbreaks in some cases. This isn’t scientifically controversial. There’s probably a literature review out there; here’s one example from the Northern Rockies

Our results show treatments designed to increase resistance to high-severity fire in ponderosa pine-dominated forests in the Northern Rockies can also increase resistance to MPB, even during an outbreak.

So “protecting” increases risks from pine beetles and wildfire, which doesn’t actually sound, in those cases, very protective.

As to the green “solar panel” well..that kind of implies an even-aged stand, which many stands that I observer are not. And then there are forests that never form continuous crowns due to competition for water.

I can understand if some don’t want to count pinyon-juniper as forests, but then maybe each kind of forest should be considered separately, including mesic and dry forests.

Here are some interesting and relevant Q&As from the ANPR.

Q. What restoration options are available to restore old-growth forest structure in frequent fire forests?

Mechanical thinning and prescribed fire represent the primary approaches to active restoration of frequent-fire mature and old-growth forest areas to reduce their vulnerability to wildfire. Reduction in tree density often increases resilience to the climate-driven impacts of droughts, insects and wildfire.

Restoration prescriptions generally aim to increase the diversity of trees – age, size, and species – and retain the largest trees of the most fire-resistant species in the area. Diverse forests are more resilient because threats are less likely to impact trees species, ages and sizes at once.

Q. Are old-growth forests climate resilient?

Many old-growth forests have resilient characteristics like thick bark, high canopies, and deep roots. Some, like coastal redwoods, require moderate year-round temperatures and abundant moisture to thrive. As such, they are highly vulnerable to shifting conditions. As climate continues to deviate from historical

norms, even otherwise resilient forests are expected to be at increasing risk from acute and chronic disturbances such as drought, wildfires, disease, and insect outbreaks. These threats heighten the vulnerability of mature and old-growth forests resulting in higher chance of forest loss.

Your thoughts?