Some of us feel like we are revisiting the past. Like I said, the mid-90’s there was a whole lot of defining going on.

I picked out this Science Finding from the Pacific Northwest Station ( nice work PNW!) because I think the authors did a good job of summarizing the definition quandary . It’s from 2003, twenty years ago, now. I thought “uh-oh” when I read the first sentence.

Not all forests with old trees are scientifically defined as old growth. Among those that are, the variations are so striking that multiple definitions of old-growth forests are needed, even when the discussion is restricted to Pacific coast old-growth forests from southwestern Oregon to southwestern British Columbia.

What is an old-growth forest?

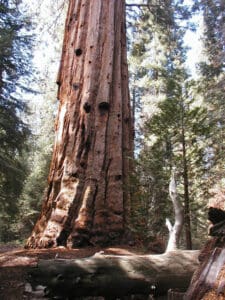

The question is not as simple as it may seem. The term “old growth” came from foresters in the early days of logging. In the 1970s research ecologists began using the term to describe forests at least 150 years old that developed a complex structure characterized by large, live and dead trees; distinctive habitats; and a diverse group of plants, fungi, and animals.Environmental groups use the term “old growth” to describe forests with large, old trees and no clearly visible human influences. Many forest scientists do not see the absence of human activity as a necessary criterion for old-growth, but there is no consensus on this in the scientific community. This publication focuses on a scientific perspective of old-growth forests; however, this viewpoint is not the only possible one.

Recently, researchers and managers from Oregon, Washington, and British Columbia held a workshop on the development of old-growth forests in the region from southwestern Oregon to southwestern British Columbia. The group looked at what scientists have learned since the first major publication on ecological characteristics of old-growth forests in 1981. They focused on coastal Douglas-fir forests, but also included closely associated types such as western hemlock and Sitka spruce forests. “Coastal” included the area from the Pacific Ocean to the crest of the Cascade Range.

By using new technologies such as canopy cranes and laser scanning, scientists are learning much about canopy complexity and development in old-growth forests.

Of many challenging topics on the 3-day agenda, the question of definitions was the first one the group discussed. Many forestry textbooks lump all old-growth forests into one stage of forest development. Most scientists now agree, though, that the term “old-growth forests” actually includes forests in many stages of development, and forests that differ widely in character with age, geographic location, and disturbance history. Even within the specified geographic area, no one definition represents the full diversity of old-growth ecosystems.Probably no single definition of old-growth forests and their values will ever exist.

“There may never be a single, widely accepted definition of old growth—there are just too many strong opinions from different perspectives including forest ecology, wildlife ecology, recreation, spirituality, economics, sociology,” says Tom Spies, research forest ecologist for PNW Research Station.Spies and Jerry Franklin, University of Washington professor, developed a generic definition of old-growth forests in 1989 for the Forest Service. The definition reads, in part: “Old growth forests are ecosystems distinguished by old trees and related structural attributes…that may include tree size, accumulations of large dead woody material, number of canopy layers, species composition, and ecosystem function.” Most scientists would now include vertical and horizontal diversity in tree canopy as an important attribute.

This definition of old growth is widely accepted but too general for forest inventory or planning. Most scientists at the workshop thought that multiple definitions of old growth are needed for the diversity of forest types within the region. Also, they thought, old-growth definitions should be finetuned to the inherent patterns and dynamics of the forest landscape mosaic of an area. “At best, we thought it may be possible to converge on a small set of definitions for inventory or mapping purposes,” Spies says.

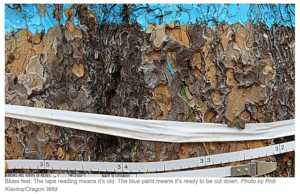

Even so, when these definitions are applied, some old forests might be just one large tree per acre below the required minimum or have too few large, down logs, and thus might not meet a rigid definition. “The boundaries of what defines old-growth forests are a lot fuzzier than we’d like,” Spies explains. “Some young forests have elements of old growth, and old growth often has patches of young forest. Where fire was common in the past, the dominant trees have a wide range of ages.” In the end, he comments, “Because we deal with complex ecosystems, we have to be comfortable with flexible terms and some ambiguity.”

My bold.

With regard to “accumulations of large dead woody material, number of canopy layers, species composition, and ecosystem function. Most scientists would now include vertical and horizontal diversity in tree canopy as an important attribute.” But fire-adapted forests often don’t have accumulations of dead woody material, number of canopy layers, horizontal diversity, as in the longleaf photo above.

Seems like a national definition would be a heavy, and perhaps unnecessary and unhelpful lift.

I’ll going to write the Sierra Club folks and ask (1) if they have a definition and (2) what projects they know of with this problem. I’ll report back. Meanwhile thanks to Susan Jane for listing a project where old growth has been called out as an issue. I’ve got another one to discuss next week, and please put any others in the comments.

Additional note: reading the Campaign it actually says “We are calling on the Biden Administration to enact a strong, lasting rule that protects mature trees and forest stands from logging across federal lands as a cornerstone of US climate policy. ” That would seem to place them at odds with the “cutting big to protect bigger” we’ve been discussing.