We’ll all need a glass or two before this one is over..

We’ll all need a glass or two before this one is over..

A hearty thank you to Nick Smith, who always has something interesting in his daily update. Here’s this one.

I don’t think anyone will be surprised to learn that people (wait for this…!) don’t agree on what is an old forest. In fact, we’ve discussed at least two incarnations of the same issue, during spotted owl days (1994), and HFRA development days (2002).

I got a chuckle out of this on Google.. question “What is the Northwest Forest Plan 1994?”

In 1994, the comprehensive Northwest Forest Plan (‘the Plan’) was initiated to end the impasse over management of federal forest land in the Pacific Northwest within the range of the northern spotted owl.

As my song parody went during the HFRA days (to the tune of They Call the Wind Maria, from Paint Your Wagon)

But old trees die, and then fall down,

And we’ve got premonitions-

But we’ll do fine,

We’ll move the lines,

And change the definitions!

Reserves, Reserves, we call those areas Reserves.

Fortunately they asked a knowledgeable prof, Dr. Mark Ashton from Yale who said:

Any definitions for old-growth or mature trees adopted by the Biden’s administration are “going to be subjective,” said Mark Ashton, a forestry professor at the Yale School of the Environment.

Already disagreement is emerging between the timber industry and environmentalists over which trees to count. That’s likely to complicate Biden’s efforts to protect older forests as part of his climate change fight, with key pieces stalled in Congress.

“If you were looking at ecological and academic definitions of old growth, it’s going to be very different from what the White House is thinking about,” Ashton said. “Even the word ‘mature’ is difficult to define.”

Groves of aspen, for example, can mature within a half century. For Douglas fir stands, it could take 100 years. Wildfire frequency also factors in: Ponderosa pine forests are adapted to withstand blazes as often as once a decade, compared to lodgepole pine stands that might burn every few hundred years.

There’s wide consensus on the importance of preserving the oldest and largest trees — both symbolically as marvels of nature, and more practically because their trunks and branches store large amounts of carbon that can be released when forests burn, adding to climate change.

But what exactly is “mature”? My discipline (always the underdog in any disciplinary discussion) would say “reproductive maturity.” I can almost hear the buzz.. wrong answer. Yes, a lodgepole stand might burn every two hundred years, but bark beetles often get them earlier. Once again, it seems like it’s difficult to get the mesic mindset (leave them alone) and the dry forest reality (they’ll get eaten or burn up or both) to form a coherent set of talking points.

Yay! Bipartisan agreement.

Concerns that warming temperatures, fires and disease could doom the dwindling number of ancient trees on federal forests drew a bipartisan group of lawmakers to California this month. They touted planned legislation to preserve perhaps the most iconic old growth in the U.S.: stands of massive sequoias that can tower almost 300 feet (90 meters).

Somehow I don’t think Hayes knows more about this than Ashton. Clearly he is quoting Groups Important to this Administration:

White House adviser Hayes described old growth forests generally as undisturbed stands with well-established canopies and individual trees usually over 150 years old.

“Mature forests,” he added, “are generally 80 to 150 years old and have many of the same characteristics of old-growth forests or are on their way to developing those characteristics if left undisturbed.”

Yes, “on their way to being old” would pretty much cover a lot of territory. Somehow the 80 number seems to have taken on a life of its own.

But let’s look at Hayes’ background. He’s a climate advisor with a background in environmental law. Interestingly, he was also a senior fellow at the Hewlett Foundation, who have a rather colonialist attitude toward the American West.

The vision of the Hewlett Foundation is to conserve biodiversity and protect the ecological integrity of half of the North American West for wildlife and people. Our goal is to conserve 320 million acres of public and private land across the North American West by 2035.

The Hewlett Foundation’s Environment Director also joined the Biden Admin working for John Kerry on climate. They also fund the Center for Western Priorities which has a good daily roundup of news but is run by political operatives, definitely with a partisan twist.

Fortunately, the Forest Service folks are (back) on this. Probably all the folks from the previous old growth efforts have retired.

Officials were developing a “workable definition” that would be made public, Hayes said. “Then based on a good definition, there will be the opportunity to … get real and protect these stands and safeguard them to the greatest extent we can from the threats that they face.”

Threats could include fire, drought, competition with younger trees, insect infestation and timber harvests, agency officials said in a statement. How those rank won’t be known until after the inventory.

I think the FS already knows how to deal with fire, drought, and competition.. take out smaller trees. And has gotten large chunks of change to do that, and also to figure out ways to use the material. Funded in the Bipartisan Infrastructure Bill and other places. Still, I’m not seeing many options, though, that will keep old lodgepoles from bark beetles.

Aside: one of the forests in Region 2 had a concern with Roadless that they wouldn’t be able to go in and get spruce beetle killed trees removed before they became an outbreak. I don’t think this made it into the Rule, though. Perhaps the FS will amend Roadless rules to enable more insect infestation prevention? Just kidding.

And from CBD:

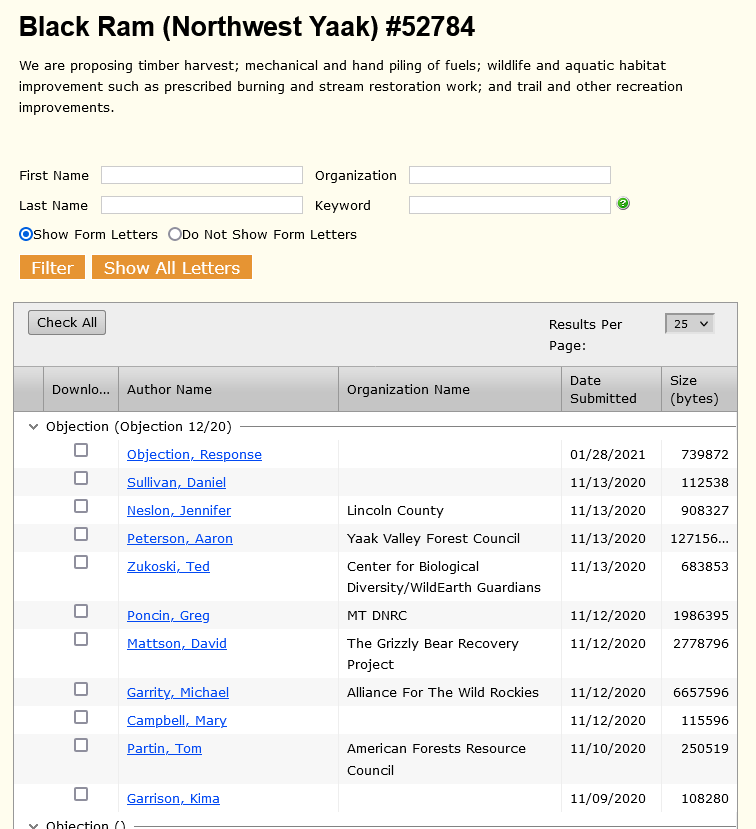

They want the administration to adopt specific rules to protect those forests, rather than vague management plans that would be easier for a future Republican administration to reverse. Environmentalists also want to stop pending logging projects on federal lands in Oregon, Wisconsin, South Dakota, Montana, Idaho and other states.

“This executive order clearly calls out the need for protections,” said Randi Spivak with the environmental group Center for Biological Diversity. “I’m concerned the Forest Service will slow walk this until the clock runs out.”

Spivak acknowledged that definitions of mature may vary among different tree species, but said complexity was no excuse to avoid acting.

“If you’re looking for one age, 80 years is a good cutoff,” she said.

No whiskey for you, Dave and Randi! It’s looking like some wine is questionable also.

Note that the FS is back to being the fall person (“slowly walk this out”) when the current Administration doesn’t do what ENGOs want.. under the Trump Admin it was all Trump’s fault. And so it goes.