Bob Zybach and I went on a field trip to the Rim Fire. The first stop on the tour showed us the Sierra Pacific Industries’ salvage logging results. I’m posting a medium resolution panorama so, if you click on the picture, you can view it in its full size. You can see the planted surviving giant sequoias on their land which were left in place. You can also see some smaller diameter trees, bundled up on the hill, which turned out to be not mechantable as sawlogs. You might also notice the subsoiler ripping, meant to break up the hydrophobic layer. They appear to have done their homework on this practice, and it is surprising to see them spending money to do this. SPI says that their salvage logging is nearly complete, and that they will replant most of their 20,000 acre chunk next spring. They have to order and grow more stock to finish in 2016.

Photos

Throwback Thursday Hits NCFP!

After the “Siege of 1987”, and 43 wildfires on the Hat Creek Ranger District, in three days, the Lost Fire burned up this forest up on the Hat Creek Rim. Even without terrain effects, this fire raged through the forest incinerating everything in its path. There is an eerie beauty in this picture, reminiscent of an Ansel Adams monochrome image.

Today, those forests are growing back, after a big reforestation program, and it appears, a subsequent thinning. Here is a Google Maps view of that area today.

https://www.google.com/maps/@40.8027893,-121.4002792,862m/data=!3m1!1e3?hl=en

Already this summer, there has been 3 large wildfires on this Ranger District. It is mostly a dry “eastside pine” forest, requiring trees to be thinned and crowns separated. It appears that the Forest Service is finally seeing that early thinning is key to restoring forests. In the past, it always appeared that they were “gambling” on waiting for the trees to get bigger (and more profitable), before managing their plantations.

In Idaho, Tracing What Remains After the Flames

Dick Boyd sent me this article featuring the Sawtooth National Recreation Area. The Stanley area is one of my favorite spots, with hot springs, jagged peaks, pristine lakes, spacious meadows and abundant wildlife.

As we neared Stanley, Idaho, a hamlet carved by creeks and framed by mountains with spiky peaks that reminded me of a punk rocker’s hair, the landscape surrounding the winding highway on which we’d climbed 7,000 feet gave way from rugged canyon to flat expanse of grass speckled by lodgepole pine and aspen. We were on the northern edges of the Sawtooth National Recreation Area, three hours from Boise, when scars from an old fire came into view.

My daughter, Flora, and I had been playing a makeshift game in which we pointed out the nature surrounding us, the sort of mindless thing you do to entertain a 5-year-old on a road trip. I see a deer, I see a birdie, I see snow, I see a purple flower, we called out.

“I see trees,” I said, pointing to a cluster of an unrecognizable species to our left, their crooked branches denuded by flames that had torched them.

“Those are not trees,” Flora retorted. “Trees have leaves!”

This article reminded me of the time I spent working on the Boise National Forest, after the massive 1994 Rabbit Creek Fire took 2 months to burn before the Sawtooths and fall rains finally extinguished it. The public rarely sees any of the 150,000 burned acres, as it isn’t visible from the highways. I stumbled upon this vintage video that shows how devastating such fires can be, as storms deposit moderate rains upon highly hydrophobic soils.

It is not always easy to display the damages that occur when soils cannot absorb even moderate rainfall. As the storms and high winds came in, that day, Forest Service employees were called in, due to the danger. Oddly enough, they forgot about me. I weathered the storm, not knowing what was happening. The next day, I patrolled the roads, finding a plugged culvert, with excessive soil movement. I pulled out my trusty shovel and diverted all the water into the roadside ditch, getting it to flow down and through the next downhill culvert.

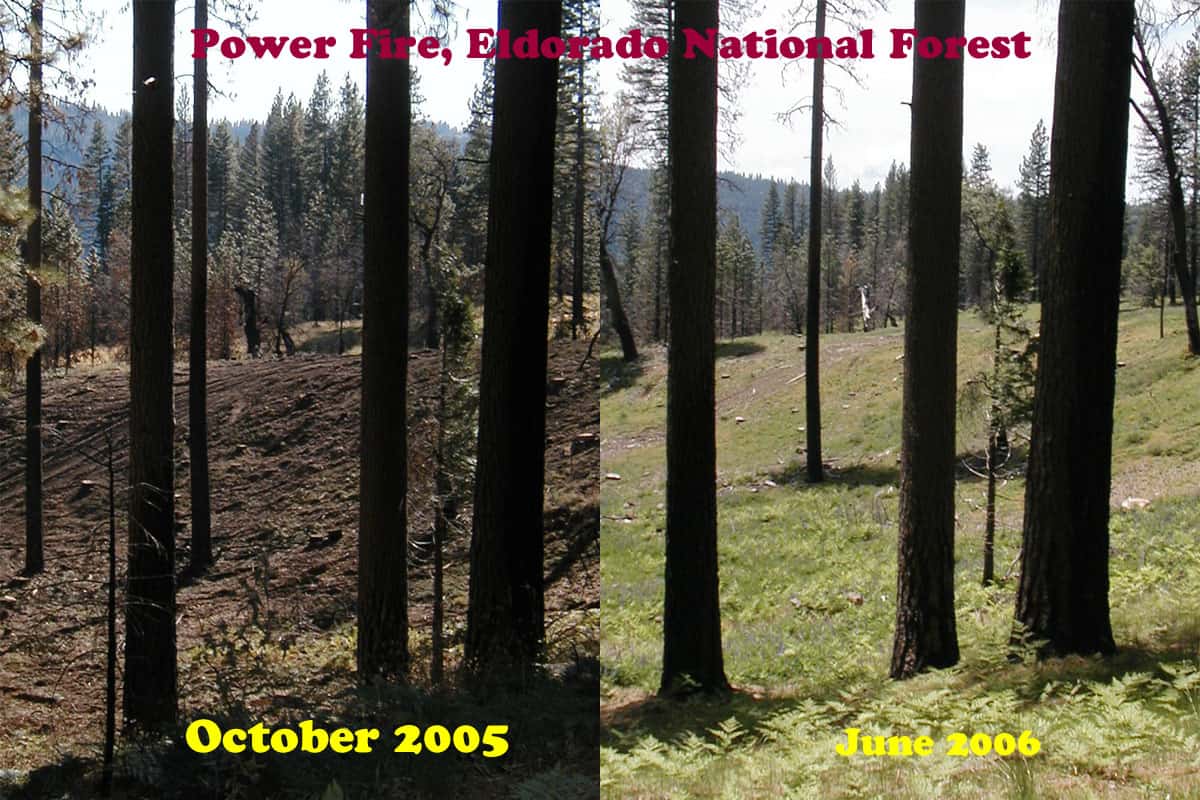

Repeat Photography: Part Deux

It’s kind of a challenge to assemble pictures shot in different years, from different spots, and from different cameras. This is an excellent way to view and monitor trends, showing the public what happens over time to our National Forests. Sometimes, you have to look hard to see the differences. In any future repeat photography projects, I will be using very high resolution, to be able to zoom in really far.

One of the reasons why you don’t see much “recovery” is that the Eldorado National Forest has finally completed their EIS for using herbicides in selected spots, almost 10 years since the fire burned. This is part of the East Bay’s water supply. Sierra Pacific replanted their ground in less than 2 years. So, the blackbacked woodpeckers should be long gone, as their preferred habitat only lasts for an average of 6 years. As these snags fall over, the risk of intense soil damages from re-burn rises dramatically. Somewhere, I have some earlier pictures of this area which may, or may not line up well with this angle. I’ll keep searching through my files to find more views to practice with.

Repeat Photography and Salvage Logging Recovery

My first attempt at assembling pictures, showing how quickly salvage impacts can “heal”. Here is the current aerial view of this specific area.

https://www.google.com/maps/@38.4831284,-120.3639833,223m/data=!3m1!1e3?hl=en

Here is a view of a re-burn that has already occurred, in the same area. Notice the lack of significant mortality, due to having salvaged the area, reducing the fuels of the inevitable future fires.

https://www.google.com/maps/@38.4770266,-120.3464336,892m/data=!3m1!1e3?hl=en

One of the biggest “purpose and needs” in the Sierra Nevada is fuels reduction after a wildfire. Otherwise, re-burns, like the Rim Fire will dominate the landscapes for an indefinite amount of decades.

Yosemite’s Re-re-Burn

The El Portal Fire, burning in Yosemite National Park and the Stanislaus National Forest, has taken a familiar path. Starting very close to where the 1989 A-Rock Fire began, it easily burned up the steep canyon slopes, out of reach of firefighters. Not too many people are making the connection between this set of fires, the A-Rock, the Big Meadow and now the El Portal Fire, and the Rim Fire re-burn (and its prior fires).

Below is what the Foresta area looked like in November. Did those green trees survive this fire? We can’t be sure until the bark beetles have decided their fate, over the next few years. The forested slopes in the background were salvaged under the original A-Rock salvage project, and you can see that it looks about as good as a burned and salvaged landscape can be. Parts of that ridge top have had 13 fires in the last 100 years. The northern third of the fire burned into areas partially burned in the Big Meadow Fire. Up there, fuels are much heavier, and some of it had made it to the ground.

Edit: The fire’s boundary has slopped over that far ridge top but, there is less fuel on that dry west-facing slope, and the fire is just smoldering at the north end. Now, with more re-burn! It will be interesting to see how intense it was, burning through the salvaged part of the A-Rock Fire.

So, how long do you think it will take to turn this former pristine old growth stand back into a viable forest? Remember, this was a prime summer site for Indians, who expended a lot of time and energy to manage the ladder fuels. You can also go see the bigger picture here, at https://www.google.com/maps/@37.7045826,-119.7624808,7211m/data=!3m1!1e3?hl=en The northern end is very close to Crane Flat. Suppression costs have topped 8 million dollars. Also, how long will it take before blackbacked woodpeckers are on THIS piece of land? We need to learn from this example, or be doomed to repeat this moonscape.

New Aerial Photos of the Rim Fire

Google Maps now has updated photos that include the Rim Fire. Now, we can explore the whole of the burned areas to see all of the damages and realities of last year’s epic firestorm.

.

Here is where the fire started, ignited by an escaped illegal campfire. The bottom of this deep canyon has to be the worst place for a fire to start. It’s no wonder that crews stayed safe by backing off.

http://www.google.com/maps/@37.8374451,-120.0467671,900m/data=!3m1!1e3?hl=en

.

While there has been talk about the forests within Yosemite National Park, a public assessment has been impossible, in the National Forest, due to closures. Here is an example of the plantations I worked on, back in 2000, completed just a few years ago. What it looks like to me is that the 40 year old brushfields caused most of the mortality within the plantations. A wider look shows some plantations didn’t survive, burning moderately. When you give a wildfire a running start, nothing can stand in the way of it.

http://www.google.com/maps/@38.0001244,-119.9503067,1796m/data=!3m1!1e3?hl=en

.

There is also a remarkable view of Sierra Pacific Industries’ partly-finished salvage logging. Zoom into this view and take a look at their latest work, including feller-bunchers. Comments?

http://www.google.com/maps/@37.9489062,-119.976156,3594m/data=!3m1!1e3?hl=en

More Rim Fire Pictures

All too often, once a firestorm goes cold, a fickle public thinks the disaster is over with, as the skies clear of smoke. In the situation of the Rim Fire, the public hasn’t had much chance to see the real damages within the fire’s perimeter. All back roads have been closed since the fire was ignited. Besides Highway 120, only Evergreen Road has been opened to the public, within the Stanislaus National Forest.

From my April trip to Yosemite, and Evergreen Road, this unthinned stand burned pretty hot. This would have been a good one where merchantable logs could be traded for small tree removal and biomass. Notice the lack of organic matter in the soil.

Sometimes people say there is no proof that thinning mitigates fire behavior. It’s pretty clear to me that this stand was too dense and primed for a devastating crown fire. I’m guessing that its proximity to Yosemite National Park and Camp Mather, as well as the views from Evergreen Road have made this area into a “Park buffer”. Now, it becomes a “scenic burn zone”, for at least the next few decades.

There is some private land along Evergreen Road, which seem to have done OK, at least in this view. Those mountains are within Yosemite National Park. Sadly, the media likes to talk about “reduced burn intensities, due to different management techniques”, within Yosemite National Park. Only a very tiny percentage of the National Park lands within the Rim Fire have had ANY kind of management. Much of the southeastern boundary of the fire butts up against the Big Meadow Fire, generally along the Tioga Pass Road (Highway 120). Additionally, much of the burned Yosemite lands are higher in elevation, as well as having larger trees with thicker bark. You can also see that there will be no lack of snags for the blackbacked woodpecker. Can anyone say, with scientific sincerity, that over-providing six years of BBW habitat will result in a significant bump in birds populations? The question is really a moot point, since the Yosemite acreage, alone, does just that.

People have, and will continue to compare the Yosemite portion of the Rim Fire to the Stanislaus National Forest portion, pointing at management techniques and burn intensities. IMHO, very little of those comparisons are really valid. Apples versus oranges. Most of the Forest Service portion of the fire is re-burn, and there is no valid Yosemite comparison (other than the 2007 Big Meadow Fire). It has been a few months since I have been up there, and I expect that there are plenty of bark beetles flying, and the trees around here have no defense against them, with this persistent drought. Everything is in motion and “whatever happens” is happening.

Rim Fire Terrain Effects

Below is a picture of the Tuolumne River and Poopenaut Valley, just a mile or so below Hetch Hetchy’s O’Shaughnessy Dam. As you can see, the area burned rather lightly. What might be the reason for this area to survive, almost unscathed? I think there is a “micro-climate” at play, here. Most of this is Yosemite National Park.

Certainly, there are plenty of fuels, and California is in a historic drought. Firefighters did not “heroically” save this area from the flames. No management was done to make this area more resilient. Comparing this area to scorched places downstream, I think I have the answer. Farther downstream, the fires were enhanced by the nearly constant breeze, flowing down during the night and morning, and flowing up, with the heat of the day. Cold air sinks and warm air rises. This spot is pretty unique along the Tuolumne River. As the canyon turns from a glacier-sculpted valley into a V-shaped gorge, the cold air from higher elevations runs into this bottleneck, pooling up in this last valley, going downstream. Temperature inversions stay longer and stabilize the breezes, reducing fire behaviors.

One thing I did notice in this area was that many single digger pines were “selectively burned” as individuals. Those long slender needles were good at catching the small embers.

Burn Intensity in the Rim Fire

I ventured into the Rim Fire, where access is (still) very limited, and found a variety of conditions. Along Evergreen Road, on the way into the Hetch Hetchy area of Yosemite National Park, I first saw an area that had a prescribed burn accomplished, a few years ago. A “windshield survey” of that saw that there were plenty of trees surviving. I wasn’t surprised to see scattered mortality. It remains to be seen how many of these green trees already have bark beetles in them. In fact, I’m sure that some trees have changed color since I was there, in late April.

Farther up the road, near the historic Camp Mather, I saw this managed area and wondered why it didn’t survive very well. You can see that understory trees were cut, reducing the ladder fuels. Farther up the gentle slope there appears to be some survivors. All of the trees in this picture are likely candidates for bark beetles, and the green ones can support more than one generation. We are already seeing accelerated bark beetle mortality outside of the fire’s perimeter.

I scanned around, looking for a reason why the stand had so much mortality. Looking across the road, down the hill, I saw the reason why. It is pretty clear that this stand hadn’t seen any management, and the hot wind from the fire pushed the crown fire across the road. Some of those trees were simply just “cooked” by the hot gases, blowing through their crowns. While I have seen these fire-resilient pines sprout some buds the next spring, few of them survive through the next summer, for multiple reasons.

With over 250,000 acres burned, of course there will be a varied mosaic, with lots of examples of things we like to talk about, no matter what your point of view is. I will post more examples of what I saw in future posts.