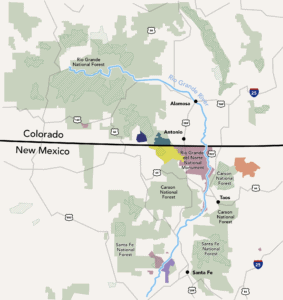

The Forest Service and Bureau of Land Management over the last several years have been developing long-term Resource Management Plans for more than 3 million acres of BLM lands in Eastern Colorado and the Uncompahgre Plateau and in the Rio Grande National Forest. According to this article, the state and local communities are not happy.

The Trump-driven shift toward more oil and gas development on public lands worries Colorado politicians and conservation groups that are steering the state toward increased protections. Agencies within the same department seem in conflict. Long-studied plans are changing between between draft and final reports, with proposed protections fading away and opportunities for extraction growing…

“What we are seeing is the full effect — in proposed actions — of the 2016 election at the local level,” Ouray County Commissioner Ben Tisdel said.

The article goes into detail about the effects on the Uncompahgre Field Office’s proposed plan:

County commissioners from Gunnison, Ouray and San Miguel counties have filed protests with the BLM over the Uncompahgre Field Office’s proposed plan. The counties have been involved with the planning for eight years. In 2016, the counties submitted comments on the plan outlining concerns for the Gunnison sage grouse and listing parcels the agency should protect and retain as federal lands.

“Alternative E proposed doing all the things we specifically asked them not to do,” said Tisdel, the Ouray County commissioner, adding that lands his county wanted protected were listed in the 2019 plan for possible disposal by the agency. “We thought we had a pretty good product in 2016 and now we have this new alternative, Alternative E, that goes way beyond anything we had seen before and is awful in ways we never thought of before.”

With regard to the Rio Grande National Forest revised forest plan:

The move from that September 2017 Draft Environmental Impact Statement to the final version released in August has riled conservationists and sportsmen. Goals established for air quality, designated trails, fisheries management, fire management, wildlife connectivity and habitat were scaled back in between the draft and final versions.

Colorado’s governor has weighed in on the BLM plan (in language consistent with the Western Governors Association policies):

The resource management plan’s “failure to adopt commitments consistent with the state plans, policies and agreements hinders Colorado’s ability to meet its own goals and objectives for wildlife in the planning area,” Polis wrote.

The BLM had an interesting response:

“There is room to adjust within the RMP, which has a built-in adaptive management strategy,” he said. “We are ready to respond as the state’s plans are complete.”

So they plan to do whatever the state wants them to do later? “Room to adjust within the RMP” appears to mean that they don’t have to go through a plan amendment process with the public, which seems unlikely to be legal for the kinds of changes the state appears to want. (It definitely wouldn’t work for national forest plans.)

The Western Energy Alliance blames the governor for being late to the game:

It doesn’t get a complete do-over just because something new happens, like Gov. Polis issues a new order.”

But it does apparently get a complete do-over because a new federal government administration says so. There may still be some legal process (e.g. NEPA) questions this raises.