The Coronado National Forest has been sued by the Center for Biological Diversity for approving the Rosemont copper mine. The U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service is also a defendant because the issues involve ESA consultation on the mine.

The Rosemont Mine would “significantly impact a number of endangered species and their remaining habitat, including one of the three known wild jaguars in the United States,” said the center.

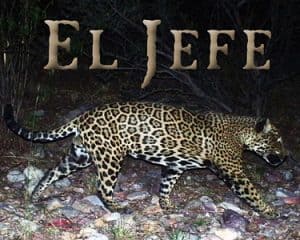

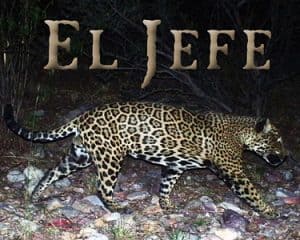

The mine’s footprint lies “squarely in jaguar critical habitat” important for the survival and recovery of jaguars in the United States, the Center said, cutting through the home territory of “El Jefe,” one of three jaguars spotted in Arizona’s mountain, the center said.

In the lawsuit, the center said that the mine would affect 5,431 acres of land in the Coronado National Forest, including hundreds of acres used as a “dumping site” for more than a billion tons of waste rock and tailings facilities. Approved by the Forest Service, the Rosemont Mine would also include hundreds of acres of fencing that would present a “permanent barrier to wildlife movement.”

“The Rosemont Mine would turn thousands of acres of the Coronado National Forest into a wasteland,” wrote Marc Fink, an attorney for the group. “Even though the agencies found it would permanently damage endangered species and precious groundwater resources, they’re letting the mine proceed,” he said.

The decision to permit the mine required a forest plan amendment. The Forest Service provided this rationale:

“I have decided to amend the 1986 Coronado forest plan by creating a new MA that provides for

mining of privately held mineral resources while allowing other forest uses to the degree that they are safe, practical, and appropriate for an active mining or postmine environment. Standards and

guidelines have been developed specifically for this new MA (MA 16). See the FEIS, pp. 117–120,

for details. In so doing, this project meets the requirements of 36 CFR 219.

I have determined that this programmatic amendment of the 1986 forest plan is not significant

because it would not significantly alter the multiple-use goals and objectives for long-term land and resource management for the forest as a whole.”

The requirements of “36 CFR 219” it allegedly satisfied were those from the 1982 planning regulations. The amendment was allowed to proceed under the old regulations because it was initiated prior to the 2012 Planning Rule. However, both sets of regulations require that forest plans provide for recovery of listed species. There could be an NFMA violation as well.