The year was 1995 (or thereabouts). I attended a Forest Service sponsored meeting on Strategic Planning at Grey Towers. I carried my brand new copy of Henry Mintzberg’s Rise and Fall of Strategic Planning to the meeting, referring to Mintzberg’s death-knell for planning whenever I could. (Here is a six-page summary pdf) A few souls agreed that Strategic Planning as envisioned by the NFMA regulation ought to have died even before Mintzberg penned his classic. But most in attendance were true soldiers from the Forest Service and a few other government agencies — looking only to do better at their assigned/accepted tasks.

Now it is 2010 and the Forest Service is once-again playing the Frame Game to make sure that the status quo planning frame is not upset too much. Or so it seems to me. As always, I hope I’m wrong. The game is to rewrite the regulatory “rule” for NFMA. If he Forest Service believes it to be a “planning rule” my guess it that the game is lost before it begins. To set a stage the Forest Service is hosting a bunch of so-called collaboration meetings. First out the chute, a Science Forum — a two-day gathering of “scientists” early this week. The outcome of the meeting will likely prove up my 1995 observation-warning that the Forest Service hadn’t (and hasn’t yet) learned its science lesson:

It is folly to assume that, “Science will find the answer,” as if science alone were the key to resolving social problems. Such thinking hasn’t been helpful to medical practitioners, engineers, even scientists when challenged to help explain the cultural mess we’ve gotten ourselves into relative to sustainability.

A framing question lingers: Why is the Forest Service once-again leading with science if the intent is to reframe policy and/or management?

On the heels of the Science Forum, the Forest Service will host three two-day sessions in Washington DC, and a series of one-day sessions in the hinterlands. Not enough time for thoughtful deliberation of what social mess (or wicked problem nest) the Forest Service is in, neither how it got there, neither how it might begin to move forward.

A framing question lingers: Why is the Forest Service once-again hosting a series of meetings to begin reframing the “rule”? Isn’t there any other way? Or is tradition rearing its head once again? Some of us have advocated for Blogs (internet discussion forums) to begin discussing serious policy matters and Wikis to actually write alternative versions of policy. (See, e.g. here.) But all, so far, is to no avail. We’ll see what will happen this time relatively soon. For now, though, let’s step back again in time.

The year was 2002. I began to preach the gospel of Panarchy: Understanding Transformations in Human and Natural Systems (Buzz Holling’s intro to the Panarchy idea), following on the heels of Barriers and Bridges to the Renewal of Ecosystems and Institutions, The Politics of Ecosystem Management, Managing the Unexpected and a few other key books. (See: Collaboration Readings for Reflective Practitioners). I continued to do so until my retirement in 2007. Nobody, other than a few who blog here, seemed to care. Nobody seemed anxious to seek a different path. At least no one in power circles seemed to care.

Inevitably each new idea that emerged was transformed into “Planning”: assess, plan, act, evaluate, plan, …. Planning swallowed up adaptive management without a hiccup. Planning swallowed up Environmental Management Systems, or almost , again without a hiccup. (my 2005-2007 EMS blog) But it was pretense. Pretend adaptive management. Pretend collaboration. Nothing remotely real about it. Still, it suited the Forest Service bureaucracy well. It could be force-fit into the rigid straitjacket of the Manual/Handbook system. Nothing would change the planning juggernaut that was launched way back in 1979.

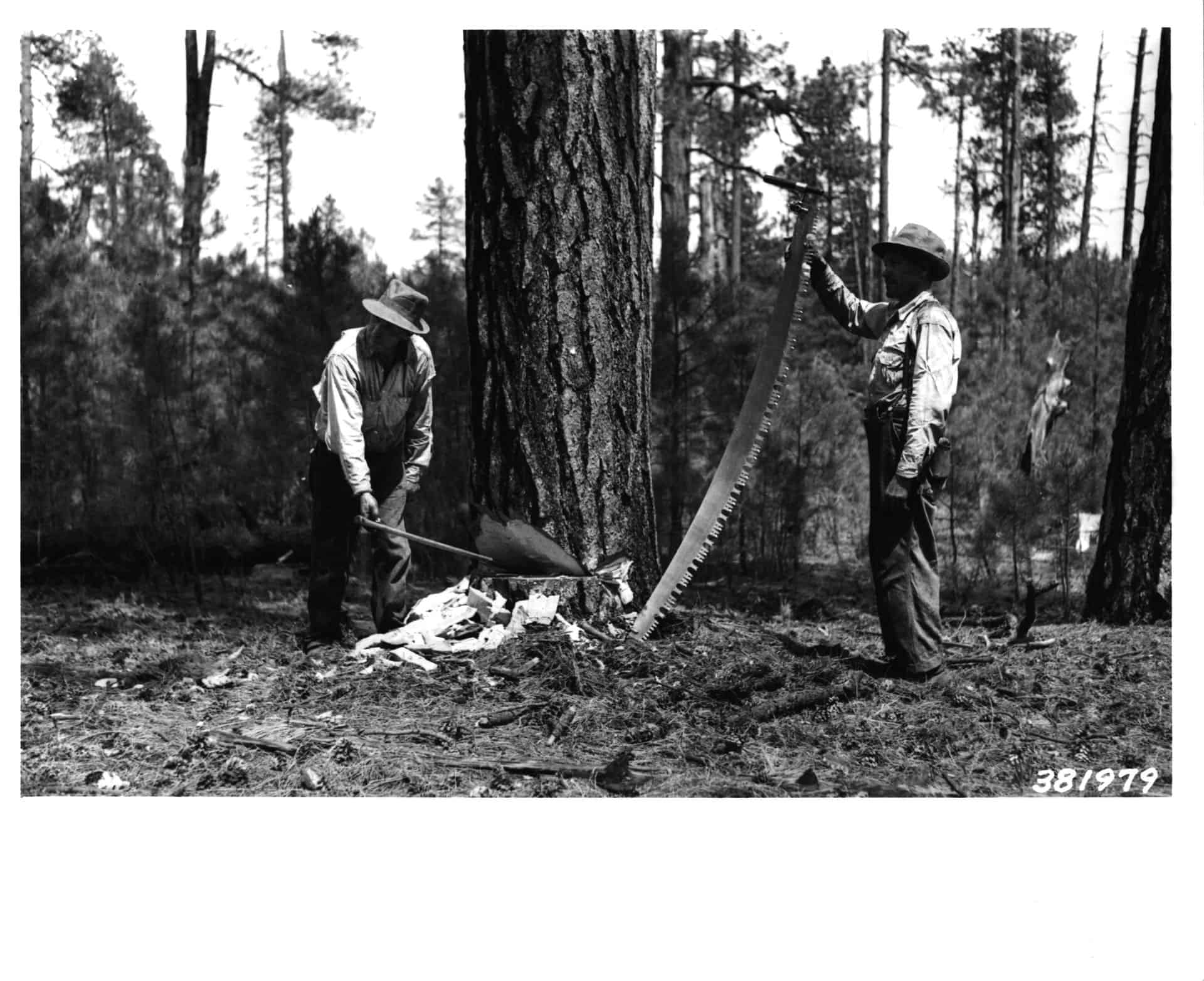

All could be pretended to be well. If only the damn enviros would just quit suing. After all the Forest Service was/is no longer rapaciously clearcutting. Never mind the mining/drilling interests, the grazers, the commercial recreation interests, etc. Never mind the suited men behind the curtains. Why can’t the enviros just settle in, kick back and enjoy (by 2009) the stimulus money that is being thrown thither and yon, some of it for so-called ecological restoration. Note: the reason the “rule” is once-again ‘in play’ is because some damn enviros sued and got the last one thrown out. (Personal admission: I am one of those ‘damn enviros’, and was long before retiring from the Forest Service.)

A framing question lingers: Did I fall into the ‘Good Will Hunting’ trap? Here is the trap in a nutshell: Badboy Will said to his psychiatrist, in essence: “You people baffle me. You spend all your money on these fancy books, you surround yourselves with ’em — and they’re the wrong fucking books.” (Great movie, btw)

Did I read the wrong books? If so, assuming that any power brokers in the Forest Service actually read, what books ought I to have been studying and preaching from. And if ideas, visions, and paths forward are not to have come from books, what ought I to have been looking for smoking?

Just a few Sunday thoughts to ponder while awaiting the meetings, and the posts that will flow here and in the official FS nonblog.