This recently filed case (the complaint is at the end of the article) hasn’t generated a lot of news coverage, but it directly raises some of the questions we have discussed at length about the effects of fuel reduction activities.

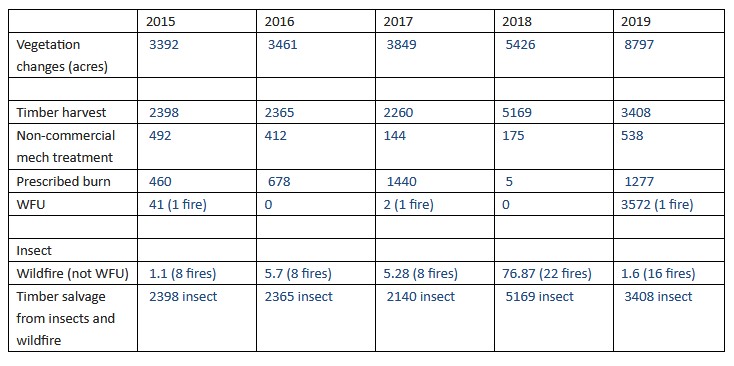

On March 26, 2021, three California conservation groups filed a complaint for declaratory judgment and injunctive relief against the Forest Service and Fish and Wildlife Service in the federal district court for the Eastern District of California (Unite the Parks v. U. S. Forest Service). They are challenging, “the failure … to adequately evaluate, protect, and conserve the critically endangered Southern Sierra Nevada Pacific fisher … on the Sierra, Sequoia, and Stanislaus National Forests …” after a substantial reduction in habitat since 2011 resulting from a multi-year draught, significant wildfires and Forest Service vegetation management. Many of the variables considered in a prior 2011 analysis have been adversely affected by these changes. The plaintiffs implicate 45 individual Forest Service projects.

This fisher population was listed as an endangered species on May 15, 2020, and the agencies conducted “programmatic” consultation at that time on 40 already-approved projects. The agencies reinitiated consultation because of the 2020 wildfires, but did not modify any of the projects. The purported rationale is that the short-term effects of the vegetation management projects are outweighed by long-term benefits, but plaintiffs assert, “There is no evidence-based science to support this theory…,” and “the agencies ignored a deep body of scientific evidence concluding that commercial thinning, post-fire logging, and other logging activities conducted under the rubric of ‘fuel reduction’ more often tend to increase, not decrease, fire severity (citing several sources, emphasis in original). The complaint challenges the adequacy of the ESA consultation on these projects, and the failure to “prepare landscape-level supplemental environmental review of the cumulative impacts to the SSN fisher…” as required by NEPA.

Not mentioned in the lawsuit is the status or relevance of forest plans for these national forests, two of which (Sierra and Sequoia) are nearing completion of plan revision. However, the linked article refers to an earlier explanation by the Forest Service that they would not be making any changes in the revised plans based on the 2020 fires because they had already considered such fires likely to happen and had accounted for them. ESA consultation will also be required on the revised forest plans, and should be expected to address the same scientific questions, arguably at a more appropriate scale. Reinitiation of consultation on the existing plans based on the changed conditions should have also occurred under ESA. (This is another area where legislation has been proposed to excuse the Forest Service from reinitiating consultation on forest plans, similar to the “Cottonwood” legislation that removed that requirement for new listings or critical habitat designation.)

(And in relation to another topic that is popular on this blog, Unite the Parks also supports the establishment of the Range of Light National Monument in the affected area.)