In 2009, the owner of a golf course in Georgia donated a conservation easement to a non-profit land trust. The easement included roughly 57 acres of primarily bottomland forests and wetlands along the Savannah River that would not be developed. That land is directly across the river from the Sumter National Forest, 700 feet away.

To obtain a tax deduction for the conservation easement, it has to be “exclusively for conservation purposes” based on one or more of the criteria in the Internal Revenue Code. They include:

(ii) the protection of a relatively natural habitat of fish, wildlife, or plants, or similar ecosystem,

(iii) the preservation of open space (including farmland and forest land) where such preservation is–

(I) for the scenic enjoyment of the general public, or

(II) pursuant to a clearly delineated Federal, State, or local governmental conservation policy,

and will yield a significant public benefit,

These issues were recently litigated by the IRS for this easement in the 11th Circuit Court of Appeals, which found the donation to be eligible as both habitat (ii) and scenic open space (iii)(I). IRS Treasury Regulations elaborate on these requirements with regard to habitat by including “natural areas which are included in, or which contribute to, the ecological viability of a local, state, or national park, nature preserve, wildlife refuge, wilderness area, or other similar conservation area.” However, the court accepted expert testimony from the IRS that the easement did not support the forest’s ecological viability.

There is no mention of testimony from the Forest Service. The 2012 Planning Rule stresses that, planning for ecological integrity must take into account “conditions in the broader landscape that may influence the sustainability of resources and ecosystems within the plan area” (36 CFR §219.8(a)(1)(iii)). In addition, where a national forest plan area can not maintain a viable population of a species of conservation concern, “the responsible official shall coordinate to the extent practicable with other Federal, State, Tribal, and private land managers having management authority over lands relevant to that population” (36 CFR §219.9(b)(2)(ii))).

The also court determined, regarding open space (iii)(II), that, “There is no qualifying federal, state, or local government conservation policy that applies to this land…” In fact, the Forest Service Open Space Conservation Strategy includes this vision: “Private and public open spaces will complement each other across the landscape to provide ecosystem services, wildlife habitat, recreation opportunities, and sustainable products.”

In this case, private land adjacent to a national forest was conserved, but there is no evidence that the Forest Service was even paying attention. The Forest Service needs to be more alert to these opportunities that would benefit national forest resources as well as contribute to greater national conservation needs. Maybe if the Forest Service promoted its conservation policies better, they would facilitate more donated easements and protect more habitat for wildlife species that also use national forests.

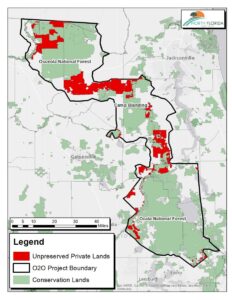

Along somewhat the same lines, conservationists in Florida are striving to conserve the Ocala to Osceola Wildlife Conservation Corridor, which would connect the two national forests of those names across 50 miles of multiple other ownerships (including a military base). Here is a presentation by the U. S. Natural Resources Conservation Service, which uses funding from the federal Farm Bill Resource Conservation Partnership Program to purchase conservation easements and create wildlife habitat on private lands within the corridor. (This is the kind of “governmental conservation policy” that should also support federal tax deductions for donated conservation easements.)

The federally endangered red-cockaded woodpecker is an excellent example of a species that the Forest Service needs to coordinate management with others for, and here’s a bit of the success story about that in the O2O Corridor.

A red-cockaded woodpecker (RCW) captured at Camp Blanding in Clay County is evidence that a project led by North Florida Land Trust to preserve land within the Ocala to Osceola (O2O) wildlife corridor is working. The bird captured at Camp Blanding was the first time this endangered species had moved between one of the national forests and the military installation since they began banding and recording the birds over 25 years ago.

“USDA Forest Service” is listed as a “partner” by NRCS, and the “National Forest Service” by the North Florida Land Trust. The latter gives me a sense of how deeply the Forest Service has not been involved, and I sure can’t find anything about this effort on either national forest website or using a national search. It’s too bad the Forest Service isn’t providing more leadership (and getting more of the credit) for conserving its important wildlife resources.