What’s all the fuss?

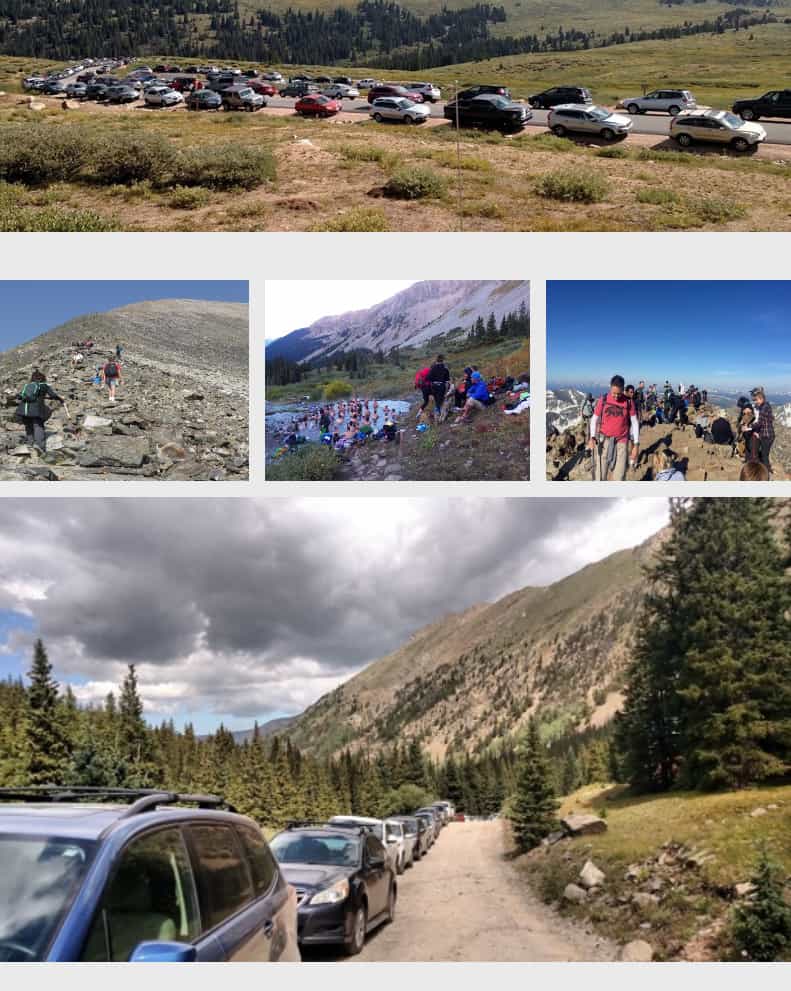

For every “supporting theme,” there’s an opposing theme. Speed, damage to trails and conflicts on trails were among top concerns drawn from that local survey.

At a meeting about e-bikes in the Springs last fall, one equestrian, Eleanore Blacketer, worried about “the ability for a bike to have higher speeds than what we might normally see.” The horse could perceive a threat, she said, and the consequences could be “catastrophic.”

While the promise of profit is there, Crandall at Old Town Bike Shop said he’s been “cautious” about growing e-bike inventory. The anecdotes he hears about are of “some people riding e-bikes that don’t know the etiquette, don’t have the knowledge of history and don’t have the skills to be going the speed they’re going on trails,” he said.

Crandall added: “There’s going to have to be some creative legislation, and maybe some money for enforcement to keep it from becoming a crazy world.”

He envisioned e-bikers traveling farther afield than they should, “having a lot more power than they do skill,” and requiring search and rescue crews. That was a shared fear in the survey.

Those are exaggerations, proponents say.

Kent Drummond, a longtime hiker in the region who has racked up 3,350 miles on his e-bike, said fellow enthusiasts weren’t as interested in the backcountry as opponents popularly believed. E-bike-riding El Paso County Sheriff Bill Elder agreed: “I think for the most part, people who are avid e-bike riders stay mostly to the urban (commuter) trails.”

But Medicine Wheel Trail Advocates, the local mountain bike advocacy group, has brought attention to the technology still developing, the capabilities still expanding along with the type of people wanting to ride.

In a statement, Medicine Wheel advised e-bikes “be regulated separately from human powered bikes” and warned “they bring the potential to significantly change the trail experience.”

A reality check was needed, Drummond said. “If there’s more traffic on trails, it’s not e-bikes. It’s bicycles in general. … E-bikes aren’t ruining anything.”

He and other e-cyclists report taking harsh, vocal scorn from other riders they pass.

“Some riders feel that riding a bicycle with pedal assist is cheating,” Wiens said. “But not everyone wants their experience to be a feat of endurance and fitness. They may just want to have some fun.”

Are they faster than standard mountain bikes?

The popular answer: Depends on who is riding.

“Typically, eMTBs are slower going downhill than traditional mountain bikes,” said Wiens, whose international organization supports e-bikes as long as access for other bikes is unaffected. “The majority of eMTB riders aren’t riding any faster than traditional mountain bikers, but of course there are always exceptions.”

Granting caveats, analyses by Jefferson and Boulder counties determined traditional mountain bikers traveled slightly faster on average.

But research is still early, and the answer to the question might vary across locales. A Portland State University study, combining data from Boulder, Tennessee and Sweden, determined “e-bikes are indeed faster on average than conventional bicycles.”

Chinese researchers published a study last year that showed human correlations with the machine. One conclusion: “As e-bike riding skill increases, the riding speed continuously increases and is constantly expanding.”

\

Are they damaging to trails?

Concluded a 2015 study in Oregon: “soil displacement and tread disturbance from Class 1 eMTBs and traditional mountain bikes were not significantly different.”

Again, Jefferson and Boulder counties found no increased harm in their assessments.

And again, because of the lack of it, research cannot be called conclusive. Some contend the weight of e-bikes, commonly 20 pounds more than traditional mountain bikes, pose greater risks to erosion, along with the motorized churning of a wheel.