The following is a guest post by Dick Powell.

I’ve long harped about the American’s disconnect between the management and use of natural resources. This disconnect leads to a question of ethics, a question I’ve raised a number of times on this blog but no one seems interested in addressing that question (certainly not our elected officials or members of the environmental community!).

I recently came across a book, The Irresponsible Pursuit of Paradise, by Jim L. Bowyer, Professor Emeritus (Univ. of Minnesota), where this question of ethics is raised.

Bowyer quotes from a speech given by Douglas MacCleery, then Assistant Director of Forest Management of the USDA-Forest Service, at the “Building on Leopold’s Legacy” conference in Madison, WI on October 4, 1999.

Though lengthy, what follows is part of what Bowyer quoted from MacCleery’s presentation.

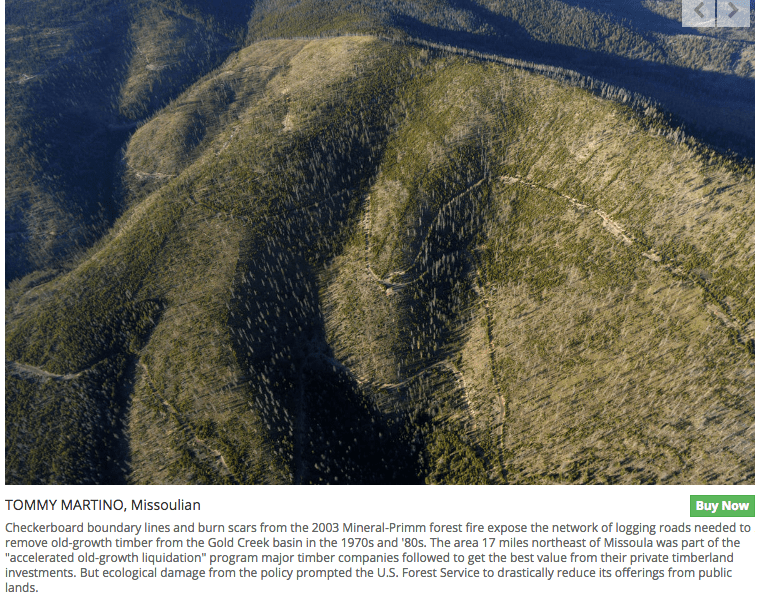

“Over the last two decades there has been a substantial shift in the management emphasis of public lands, particularly federal lands, in the United States. That shift has been to a substantially increased emphasis on managing these lands for biodiversity protection and amenity values, with a corresponding reduction in commodity outputs. Over the last decade, timber harvest on National Forest lands has dropped by 70 percent, oil and gas leasing by about 40 percent, and livestock grazing by at least 10 percent. [Keep in mind, this was presented in 1999.]

Many have attributed the move to ecosystem management or ecological sustainability to a belated recognition and adoption of Aldo Leopold’s “land ethic” – the idea that management of land has, or should have, an ethical content.

While a mission shift on U.S. public lands is occurring in response to changing public preferences, that same public is making no corresponding shift in its commodity consumption habits. The “dirty little secret” about the shift to ecological sustainability on U.S. public lands is that, in the face of stable or increasing per capita consumption in the U.S., the effect has been to shift the burden and impacts of that consumption to ecosystems somewhere else. For example, to private lands in the U.S. or to lands of other countries.”

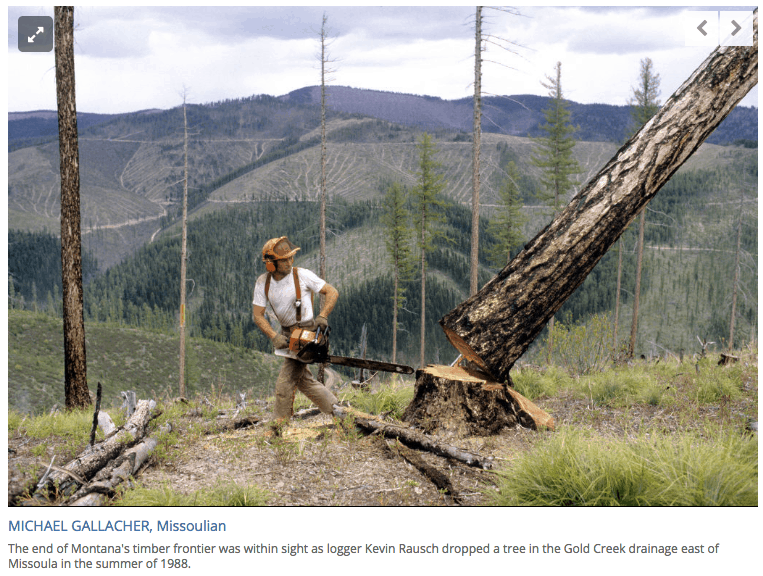

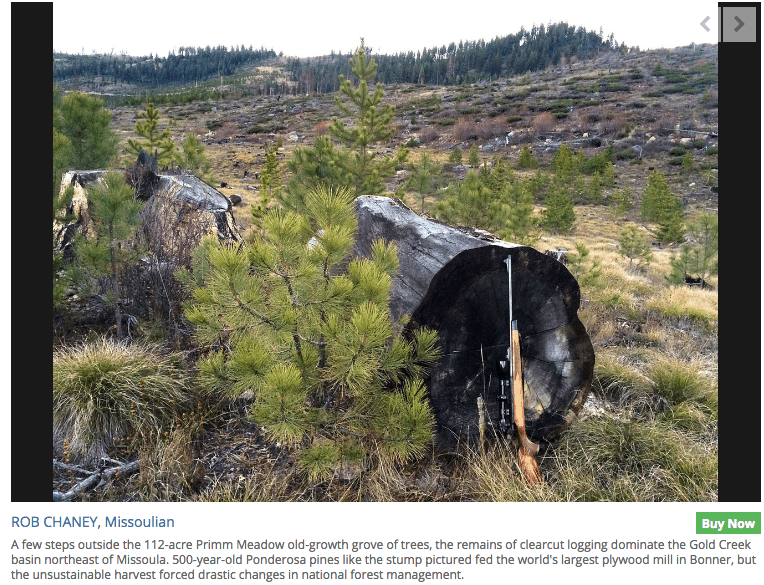

MacCleery goes on to tell about how, between 1987 and 1997, annual federal timber harvests dropped from about 13 billion to 4 billion board feet. With high consumption, the effect was to simply transfer harvest to private U.S. lands and to Canada. Those Canadian imports rose from 12 to 18 billion board feet and from 27 to 36 percent of U.S. softwood lumber consumption – much of those imports came from native old-growth boreal forests. [That we strive to “save” our old-growth forests but then blindly consume Canada’s less productive old-growth boreal forests should, all by itself, raise a question of ethics!]

Since the first Earth Day in 1970, average American family size dropped by 16 percent while the average family home increased 48 percent.

MacCleery continues: “The U.S. conservation community and the media have given scant attention to the “ecological transfer effects” of the mission shift on U.S. public lands. Any ethical or moral foundation for ecological sustainability is weak indeed unless there is a corresponding focus on the consumption side of the natural resource equation. Without such a connection, ecological sustainability on public lands is subject to challenge as just a sophisticated form of NIMBYism (“not in my back yard”), rather than a true paradigm shift.

A cynic might assert that one of the reasons for the belated adoption of Aldo Leopold’s land ethic is that it has become relatively easy and painless for most of us to do so … because it imposes the primary burden “to act” on someone else.

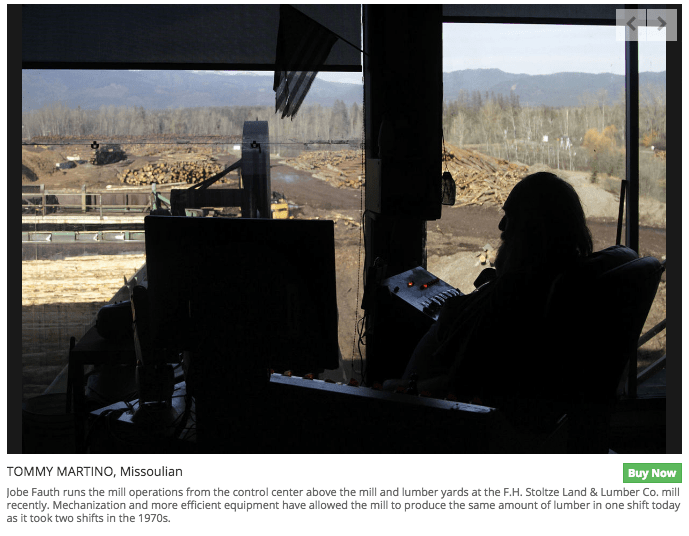

The disjunct between people as consumers and the land is reflected in rising discord and alienation between producers and consumers. Loggers, ranchers, fishermen, miners, and other resource producers have all at times felt themselves subject to scorn and ridicule by the very society that benefits from the products they produce. What is absent from much environmental discourse in the U.S. today is a recognition that urbanized society is no less dependent upon the products of forest and field than were the subsistence farmers of America’s past. This is clearly reflected in the language used in such discourse.

Rural communities traditionally engaged in producing timber and other natural resources for urban consumers are commonly referred to as natural resource “dependent” communities. Seldom are the truly resource dependent communities like Boulder, Denver, Detroit, or Boston ever referred to as such.”

MacCleery then quotes Aldo Leopold (1928): “The American public for many years has been abusing the wasteful lumberman. A public which lives in wooden houses should be careful about throwing stones at lumbermen … until it has learned how its own arbitrary demands as to kinds and qualities of lumber, help cause the waste which it decries …“The long and the short of the matter is that forest conservation depends in part on intelligent consumption, as well as intelligent production of lumber.”

Bowyer goes on to quote MacCleery: “To take off on that theme, … the evidence that no personal consumption ethic exists today is that a suburban dweller with a small family who lives in a 4000 square-foot home, owns three or four cars, commutes to work alone in a gas guzzling sport utility vehicle (even though public transportation is available), and otherwise leads a highly resource consumptive lifestyle is still (if otherwise decent) a respected member of society. Indeed, her/his social status in the community may even be enhanced by virtue of that consumption.”

Bowyer concludes quoting from MacCleery: “Ecosystem management or ecological sustainability on public lands will have weak or non-existent ethical credentials and certainly will never be a truly holistic approach to resource management until the consumption side of the equation becomes an integral part of the solution, rather than an afterthought, as it is today. Belated adoption of Leopold’s land ethic was relatively easy. The true test as to whether a paradigm shift has really occurred in the U.S. will be whether society begins to see personal consumption choices as having an ethical and environmental content as well – and then acts upon them as such.”

I’ve long understood that a very large part of American society does not like what I do for a living. If they want to put me out of business, the only thing they have to do is to quit buying wood – a very simple matter of economics. However, a forest landowner’s accountant/tax advisor would probably say that, if no one wants to buy wood, the landowner would have no reason to plant or otherwise take care of the forest and they’d be ahead to convert that land to some other use. Further, the consumer would have to depend much more heavily on alternative raw materials – petroleum, concrete, mining, etc. – all things that have far greater environmental cost both here and abroad.

Forest management and wood consumption are so inter-connected that one cannot be looked without looking at the other. To do so creates an ethical question.