For the past 11+ years I have been writing a series of article/editorials for Oregon Fish and Wildlife Journal, which has a circulation of 10,000 mostly rural Oregon businesses and residents and all Oregon elected officials. Several times I have used this forum to “peer review” the facts, analyses, and opinions that have comprised an occasional entry in the series. This is another one of those instances, and mostly focuses on two radio interviews I did with Lars Larson on his radio show this past summer.

The article draft is more than 3800 words and has six illustrations with captions, so I have only included a few of the illustrations and excerpted the mostly informative and provocative text in this post, angling for discussion. For those interested, I have posted the entire draft here — publication will probably be in a month or sooner: http://nwmapsco.com/ZybachB/Articles/Magazines/Oregon_Fish_&_Wildlife_Journal/20230923_Lars_Larson/Zybach_DRAFT_20230917.pdf

*******************

[October 12, 2023 UPDATE: The article has now been published in the current issue of Oregon Fish & Wildlife Journal. Publisher and editor Cristy Rein has noted that the magazine’s 10,000 circulation includes: “free magazines to every US Senator, all of the US Congress, the entire Executive Cabinet and committees, every elected state rep in: Oregon, Washington, Montana, Idaho, Nevada, California, Utah, Arizona and New Mexico.” Here is a link to the article, and including one-page editorials by Cristy and by Jim Petersen of Evergreen Magazine: http://nwmapsco.com/ZybachB/Articles/Magazines/Oregon_Fish_&_Wildlife_Journal/20230923_Lars_Larson/Zybach-Larson_20231010.pdf]

*******************

Conversations with Lars: Summer of ’23 Smoke & Fire

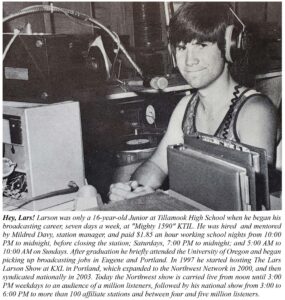

I’ve never met Lars Larson in person, but my first radio interview with him was about 20 years ago as I was finishing my graduate degree at Oregon State University. The questions likely had something to do with the Biscuit Fire at that time, or the Donato Study, which was in the news.

Since then we have had many more conversations on air, with discussions mostly focused on spotted owls, wildfires, forestry, or the Elliott State Forest. These are subjects of particular interest to me, and it’s always a pleasure talking to Lars — usually in nine-minute increments between commercials — given his own knowledge of these topics.

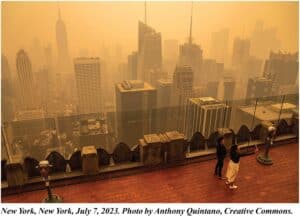

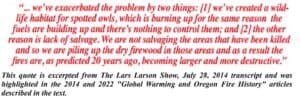

Because of Lars’ close familiarity with forestry, Northwest history, wildfires, and wildlife, his interviews are more like discussions or conversations than typical interviews. For that reason I decided to use the transcript from our recorded July 28, 2014 talk as the basis for an article/editorial in this series. The topic was the ever-increasing severity, frequency, and extent of Oregon catastrophic wildfires — as I had been clearly predicting for many years — and “climate change” as a possible cause. The article appeared in the Fall 2014 issue of this magazine, titled “Global Warming and Oregon Wildfire History,” and was generally well received.

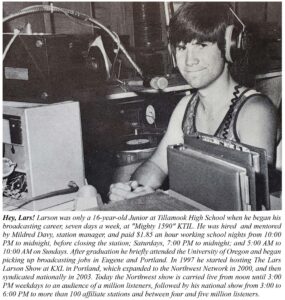

This summer I had wildfire-related conversations with Lars on two of his shows. In July we discussed the smoke from Canadian wildfires polluting US air, and in August the topic was the deadly fire in Hawaii. Audio recordings of both interviews were critically well received by several national and regional experts in wildfire management and mitigation, and I decided to resurrect the 2014 format for this article.

***********************

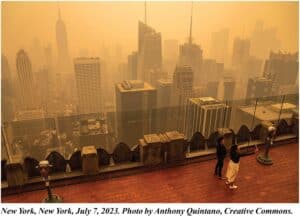

July 7, 2023: SMOKE

Lars: Welcome back to the Lars Larson Show, it’s a pleasure to be with you, and I’m always glad to get to your phone calls and your emails. On this First Amendment Friday, we celebrate your first amendment rights of free speech, free expression, and the right to associate with anyone you want to associate with.

Now, I want to ask you about this. You’ve seen what happened when wildfire smoke got into New York City and all of a sudden, the elites were breathing that orange air, and you’ve seen the same kind of thing happen this year in Seattle, they’re breathing smoky air as well. And in recent history in the Pacific Northwest, we’ve seen plenty of occasions where the smoke went on for weeks and weeks and weeks.

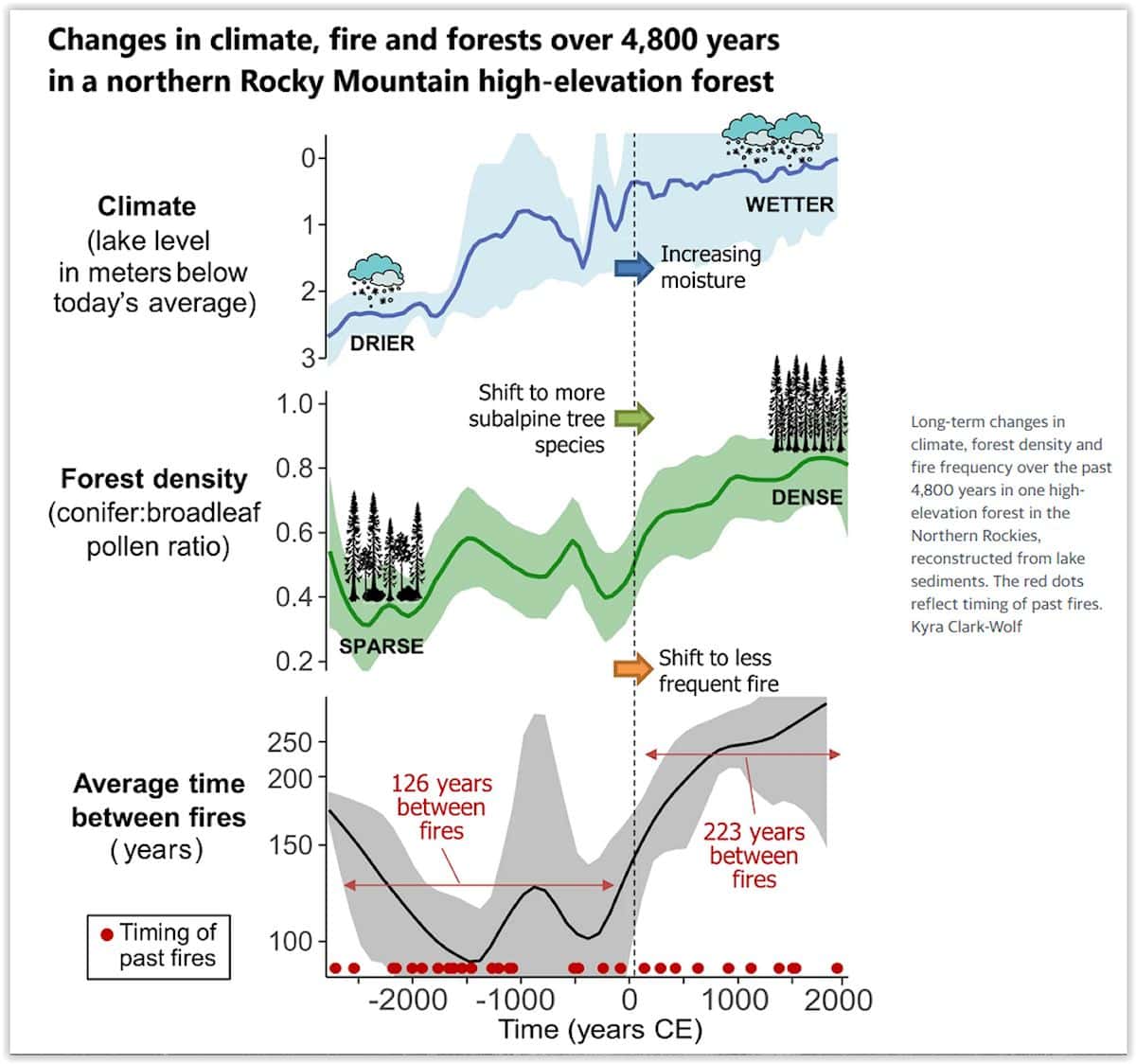

Lars: I’m glad to have you here because I want you to prepare my audience. I know this summer we’re likely to get even more smoke in the Pacific Northwest. We’re going to have fires. We’ve gone from the 30-year period you talk about frequently from I think the mid-fifties to the mid-eighties where we had essentially no large fires in the forest. Thirty years of no large fires at all, and now routinely half a million acres burn in Oregon. Half a million acres I think, on an average year burn in Washington, and we’ll expect to have fires this year as well. And I know to a fair certainty, the people in charge are going to say, “Yep, it’s all evidence of global warming.” Help prepare them with some answers for those people who say those things to them.

Bob: Well, it’s all due to fuels and weather. Global warming hasn’t happened here, so it can’t be global warming. We’ve got the same weather we’ve had for centuries. Fire season is the problem. East winds are the danger. So with the Labor Day Fires three years ago, we had east winds in early September, so we had massive fires.

The real problem is managing the fuels. From ’52 to ’87 we had one major fire, on the Smith River in 1966. It was 40,000 acres. So that’s 30 some years with one major fire. It doesn’t even compare to the Labor Day Fires — on one day, where close to a million acres burned. The Coast Range doesn’t get lightning; Southwest Oregon gets lightning but doesn’t have a lot of people; and the Western Cascades gets lightning and has a lot of people. So once we get a heavy east wind, assuming we do, ignition can come from lightning or people and large fires are the result. And largely because of the massive fuel buildups on federal lands over the last 35 years.

Lars: Dr. Zybach, there’s one thing I hear the media do constantly and they say, “Wildfires get worse during hot times.” Is there anything about a day being either 80-degrees or 105-degrees that makes a difference in terms of fire?

Bob: It’s the east wind. You can have an 80-degree or 105-degree fire; maybe at 105 degrees, depending on fuel moisture, you could have a cleaner burn and easier to control by that measure, but it depends. The fire will create its own wind, will create its own weather. They can even create thunderstorms, the big fires. But an east wind is the constant element that goes with all the major fires in Western Oregon over the last few hundred years.

Lars: So when you see these fires, you’ve studied this subject, you studied 500 years of it, 1491 to 1951. Are there ways to get on top of this problem where we could prevent these fires instead of merely trying to put them out every year and usually succeeding only to the extent that we contain them to half a million acres; instead of maybe 10 or 20,000 acres a year on an average year in that period you documented from the fifties to the eighties?

Bob: Yes, and it would be the same thing. It would be active management. Right now, the Forest Service and BLM are planning to leave all the snags and large woody debris. Jerry Franklin says a sign of a healthy forest is a lot of dead trees. That’d be like saying a sign of a healthy city is a lot of dead people. It doesn’t make sense. That’s not healthy. It’s a fuel and it’s dangerous.

So we used to harvest snags, dead trees, focus on it. We used to maintain the roads and trails and keep them open. We used to have local employment where local people that knew the roads and the land and the animals were the ones that were doing the logging and the tree planting and so on. And so we didn’t have fires. So we know how to mitigate these fires and that’s why they’re so predictable.

Like myself and others in the early nineties said, “If we create these LSRs and other government acronyms, we’re going to have massive wildfires and they’re going to kill wildlife and some people, destroy homes, and it’s going to be at a cost to rural communities that lose the work associated with forest management.” So we know how to fix the problem. We just don’t.

Lars: I’m just curious, do you have any insights as to why the people who followed you in forest science, I mean you’ve been in forest science for decades, why the people who are now coming into it seem to think that forests that burn on a regular basis or forests with lots of dead fuel on the forest floor are a healthy forest? Why the change?

Bob: Well, indoctrination. Eisenhower warned us that the government will get big computers and put independent scientists out of business. And essentially, if you cut to the chase, it’s anti-logging activists. A lot of people in the eighties and nineties thought that clearcutting was an evil. And so they picked spotted owls and marbled murrelets and coho as animals that they claimed — erroneously, still erroneously — were harmed directly by clearcutting, and got the lawyers in Washington DC and the lawyers on the ground to pursue that. And they’ve been very, very successful. And wildfires are the predictable result.

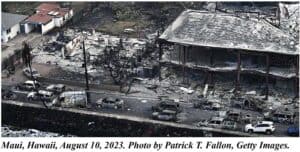

August 14, 2023: FIRE

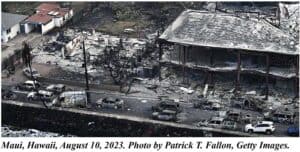

Lars: Welcome back to the Lars Larson Show. It’s a Tuesday. It’s the Radio Northwest Network, and it’s my pleasure to be with you. And now we have the deadliest fire in US history in Maui and northwest communities under evacuation orders from wildfires. What has put us in this spot and how do we get out of it?

Lars: I want to get your take initially about what happened in Maui because we’re now starting to see not just where the blame may go to power lines or other conditions like that, but almost everybody on the left politically says, oh, this is all about climate change. This is something that’s come on us because human beings use too many fossil fuels. Any truth to that?

Bob: None. It has got nothing to do with climate change. Everything to do with housing, exotic weeds, in the case of Hawaii; which is similar to Paradise and similar to the Almeda Drive fire in that weeds and housing that were very close together formed the primary fuels and in all three cases were deadly. People died because of the speed in which the fire moved.

Lars: Well, and weeds in the case — I know when people hear weeds, they say well, everybody has weeds, but is it worse in places like Maui? Because as I understand, that used to be a big area for growing sugar cane and then sugar cane has gone away to a large extent, and as a result, there’s a bunch of land that’s not very well tended but it could be, couldn’t it?

Bob: Yeah, and it’s the same thing. Almeda Drive was weeds. They created a “Greenway” and it grew up in blackberries, and those blackberries are real volatile when they die and form a canopy, and that’s what happened there; that and a lot of trailer houses and a lot of weeds. In Hawaii it was weeds that grew up in the agricultural areas that had been abandoned or converted to housing and then the housing is essentially dead trees. It’s dried lumber that’s built the houses, and if they’re close together, there’s no way to make them “Fire Safe.” Each house is fuel for the adjacent house.

Lars: And is part of the problem that in Lahaina especially, they called the place historic. It had a lot of buildings that went back before modern building codes. If they had said, well, even without building codes, we have to do something to keep these houses if one catches fire from spreading to the next one. This was all foreseeable and preventable. Am I wrong?

Bob: No, that’s exactly right. When we find — a wind will whip up in different directions. Here in Western Oregon, it’s from the east, and in Hawaii, I’m guessing it might be from any direction — but when weeds and fuels, volatile fuels, are adjacent to flammable buildings where people live, it’s a risk and we’re seeing the results of that risk.

Lars: Now, what about the Northwest communities? We’ve got a bunch of communities that they’ve gone to evacuation, mandatory evacuation. Are those also evidence that we’re not managing the forest and the wildlands very well and we could be?

Bob: We’re doing a terrible job there. These fires were predictable for the last 30 years. If we look at the Flat Fire right now, the heat isn’t a real problem. It means fuels burn cleaner and faster. But if a wind comes up, if a Chetco Wind comes up, an east wind comes up, we’re asking for another Silver Complex or Chetco Bar Fire, just a real disaster. And the way we can tell that is the Flat Fire. It’s well contained at about 33,000 acres that used to be called a major fire 20 years ago. Now it’s got to be a hundred thousand acres to be a major fire, but you look at the photos and it’s completely surrounded by snags from earlier fires. So these fires are just fueling future fires just like the Tillamook Fires in the 1930s and ’40s did. And it wasn’t until we removed the snags, took out the fuels and actively managed that land that we were able to create Tillamook Forest, and we’ve got the same problem in Curry County. They’re just allowing the snags to remain in place and fuel the next fire, and it’s been going on since 1987.

Lars: I’m talking to Dr. Bob Zybach, who’s a forest scientist and the president of Northwest Maps. The other thing is they don’t just allow the snags to stay there. Correct me if I’m wrong, but the “Greeny Groups” say, “No, you will not go in and salvage log. No, you will not take down those snags. That’s part of Mother Nature. We have to leave it there.” And they insist on leaving it there and not clearing the fuel and not replanting. I’ve seen that demand a number of times. And they could actually do that, and maybe even make the money to pay the cost of doing the replanting, couldn’t they?

Bob: Sure. We did that for 30 or 40 years. When we studied the Tillamook, we figured out if we salvage this material, we’re making money, we’re paying taxes, we’re training people, we’re keeping access roads open. And so from ’52 until ’87, we had one major fire, one fire in excess of 10,000 acres in Western Oregon. Now we have a fire that big right now that we’re holding and calling contained, or 56% contained. So it’s a problem that’s become exacerbated through mismanagement of our federal lands specifically, but now that’s being transferred over to our private and state lands as well. The Elliott State Forest, they have no plan to harvest any snags, so it’s just asking for a disaster at some future point.