The essay that forms the second part of this post — which he terms “Notes” — was written by Chad Oliver after a recent field trip to Montana to document and discuss grizzly bear habitat management with Jim Petersen for Evergreen Magazine: https://evergreenmagazine.com/this-is-very-promising/

I have been a friend and occasional collaborator with Jim for more than 30 years, since the early 90s. At that time he was interviewing me for an article regarding the Clinton Plan and first introduced me to Oliver’s work — largely because we were both clearly predicting that catastrophic wildfires would certainly follow if the Plan were adopted. The Clinton scientists and their followers were promising something entirely different: a utopia in which people were not present, but giant trees, flocks of owls, and streams filled with fish were everywhere and people who lived in cities and towns were pleased with that knowledge.

People who have read or contributed to this blog for a while know that I have a strong bias against forest management acronyms, anonymous trolls, and the use of computer models for long-term planning. The Clinton Plan was built on Norm Johnson’s FOR-PLAN computer model and featured the “old-growth” promotions of Jerry Franklin. By combining the two men’s skills with ESA “critical habitat” definitions for a wide variety of species (mostly spotted owls and fish to begin with), some LSRs, WSOs, WTFs, FMPs, and the support of key politicians, the media, and skilled lawyers, they were able to transform the public forests of the western US in just a few years.

I knew Norm fairly well at the time, when he was a professor and I was a middle-aged student at OSU. We were both in the College of Forestry and had previously participated in constructing a management plan for OSU Research Forests, where I headed cultural resources management as a part-time employee. During the beginning “Gang of Four” FEMAT phase of the Clinton Plan, he even hired me to do research, but we soon parted ways when it became obvious that his computer printouts and my historical documentation didn’t match.

A forest ecology class I had taken featured a visiting scientist, a well-known Franklin acolyte, that lectured on old-growth “biodiversity” theories and spent time making us memorize the phrase: “non-declining, even-flow, naturally functioning ecosystem.” This was a wordy way to describe a “climax forest” or, as Franklin called it, a “healthy forest.” When I pointed out that such an environment had never existed on earth I was ignored. When I later presented research to prove my point, I was canceled from academia.

According to Jerry, a “healthy forest” had large, very old trees, a “multi-layered canopy” of various tree and shrub species, lots of every kind of animal that is going extinct because of logging, big, dead standing trees scattered everywhere, and large chunks of wood (CWD and/or LWD on printouts) on the forest floor, and everything in equilibrium: trees growing at the same rate they were dying and populations of all old-growth ecosystem-dependent animals high, and stable. Man was presented as a pathogen in such an environment and had to be removed and his tools and roads abandoned in order for “Nature” to become “healed.”

This is actually a fairly accurate description of what students were being told, and current public forest management policies are largely based on this vision. Why such a condition was, and still is, seen as desirable — much less attainable — is a matter of history and philosophy, where an ideal environment is one in which “man is a visitor who does not remain or leave a trace.” Why this perspective persists in the face of decades of documented failure, wildfires, dead animals, rural poverty, burned homes, and polluted air remains a mystery.

This condition of passively managed federal lands and the predictable wildfires and rural unemployment that follows is based on what Oliver terms “out-of-date” science. His research, first published in book form in 1990, had shown that forests were dynamic: that fires, wind, shade, bugs, diseases, floods, and landslides created constant disturbances that resulted in different combinations of plants, animals, and forest structures over time.

My research showed that people were one of the principal disturbances involved in this process. Where Jerry states that a “climax forest” is a desirable management objective, Chad shows that such a condition has never existed and never can; where Jerry claims a healthy forest is characterized by big, dead, and dying trees, my research shows that a healthy forest is characterized by the presence of healthy people. Chad’s and my research are in agreement, our predictions have proven accurate, and we used traditional scientific methods and not computer models to arrive at these conclusions.

For thousands of years people had gathered and used wood as their principal cooking and heating fuel, primary construction materials, and for tools, carvings, weapons, and other uses. Villages, campgrounds, and travel routes along ridgelines and waterways had little or no wood, and seasonal broadcast burning of oak savannahs, berry patches, and tarweed fields over millions of acres removed any fine fuels or dry wood in those areas. Until recent times, local people have always managed the forests they lived in or near and wildlife has always adapted, migrated, or evolved.

Which was another thing that has concerned both me and Oliver — and Petersen — the terrible effect such a plan would have on the rural families, communities, and industries that had been working and living in and near the public lands. The local people and actual experts who have always managed the environment they lived in and near, until now. At the end of his Notes he cites and links this source: https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-024-01411-y

*******************************

Applying up-to-date Science to Solve the Forest Endangered Species/Fire/Forest Livelihoods Issues: Notes from a field trip hosted by the Evergreen Foundation

By Chad Oliver,

Pinchot Professor Emeritus, Yale University.

[email protected] May 20, 2024

The ongoing rural community issue, spotted owl issue of the 1990’s, the forest fire issue of the 2000’s, and the current grizzly bear issue are all the result of applying the same, out-of-date science.

A dramatic change in the world’s scientific understanding of forests occurred between 1980 and 2020. A book, Forest Stand Dynamics (1st edition 1990) synthesized these changes. This book has been cited in over 4,000 scientific articles worldwide, indicating the overall acceptance of the new understanding.

Change in understanding of Forests:

Old theory: The out-of-date theory assumed forests grew to a stable, natural condition known as a “Climax.” With less communication and travel, natural disturbances were rarely noticed; and so all disturbances were considered unnatural and should be prevented.

If a disturbance occurred, it destroyed the “natural condition.” The forest supposedly regrew as some plant species entered soon after the disturbance and “prepared the way” for later arriving species–which prepared for still later-arriving species in a relay-fashion until species that could replace themselves formed a “stable, climax, natural” condition (Figure below). Since this climax was natural, it was assumed to harbor all species. So, all species could survive as long as the forest was not disturbed.

Consequences of early “pristine forest” scientific theory:

A vocal “environmentalist” public emerged that wished to protect the forests and species. They mistakenly followed the outdated “pristine forest” theory and promoted no manipulation of forests. The environmental movement was joined by opportunists who collected money to stridently lobby to “save the forests.”

Just as COVID could not be cured by drinking bleach, the forest issues were not resolved—and will not be resolved–as long as incorrect, out-of-date science is applied to forests.

Assuming that the “pristine” forest was harmed by human intervention, people adhering to the old understanding who wanted forest values tried to exclude people from forests and vilified those people who lived or worked in forests.

New Understanding: Beginning about 30 years ago, scientists realized that forests were much more dynamic. Natural disturbances were a natural part of forests and indigenous people had also manipulated them for thousands of years. Trees within a forest competed with each other for resources—sunlight, moisture, nutrients—rather than mutualistically “helping” each other. The resulting pattern of forest growth can be shown in the figure below.

Forests can generally be divided into “stands”—each stand is a contiguous area of similar species, soils, and disturbance history and so has a relatively uniform structure–distribution of vegetation sizes, spacings, ages, species, etc.

Forest stands pass through similar structural stages in many parts of the world :

1) Stand initiation stage (Open structure): Following a disturbance that destroys all trees in the previous stand, a dense diversity of woody and nonwoody herbs, shrubs, and trees invades. This structure supports many grazing and browsing species and their predators, since the green, edible vegetation is accessible near the ground.

2) Stem exclusion (Dense structure): After a few years or decades (depending on the soil and type of disturbance) the newly invaded plants occupy all of the soil, light, and moisture “growing space” within the stand. Then, new plants are excluded for a few to many decades, after which the existing plants “lose their grip on the site’s growing space.” (Some species can live in the shade and remain small as other trees grow, giving the impression that they are younger and continuously invading the stand (Figure below). This appearance helped give rise to the out-of-date theory described earlier.

Forests in this structure cast heavy shade and so contain few herbs and shrubs close to the forest floor. Consequently, few animal and plant species live in it. In addition, the young trees are often crowded and susceptible to insect outbreaks, falling over, and/or burning up.

3) Understory reinitiation (Understory structure): New species that can live in shade invade the stand as the older trees age, “lose their grip on the site,” and sometimes die. The new species often do not grow much, but do supply some browse and hiding cover for more animals than in the “stem exclusion stage.”

4) “Complex stage” (Old growth structure): Eventually, some overstory trees die through windthrow, diseases, etc. and younger trees grow into the upper canopy, producing a stand of a large diversity of tree heights, ages, species, and containing dead standing and fallen trees. A variety of specialized animals such as owls and flying squirrels live in this structure.

This structure, too, can be fire-prone and so is often found in fire-protected topographies.

5) Unevenage stands: Partial disturbances are not as common as once thought,but kill various amounts and sizes of trees. A common Uneven aged structure is the “savannah,” where a few large trees are standing. These favor woodpeckers, other birds, and some grazing animals; although the presence of large trees where predators can hide and attack grazers can hinder some animals.

The new scientific understanding means that not all of a forest provides habitat for all species. Consequently, at least some amount of each structure is needed to provide all species–and so all values–from the forest; an excess of one structure can create problems (e.g., fires in the dense forests) and reduce the area and thus benefits of other structures. Also, some parts of an area will always change from one structure to another through growth or natural disturbances, so other parts of the forest need to replace the structures being lost if all structures—and species and other functions–are to be maintained.

The forest problems of threatened species and impoverished rural people have been caused or exacerbated by applying the outdated science to several issues even though more scientifically up-to-date solutions were known, available, and feasible.

1) Spotted owl issue: The spotted owl was recognized as an endangered species that lived in the Pacific Northwestern United States in the older structures of complex, late understory, and closed-canopy stands with a history of partial disturbances. Many, but not all, stands of old growth structure had been harvested before its threat of extinction was recognized. These harvested stands were temporarily in the open structure, but most had grown to the more long-lasting, dense (stem exclusion) structure.

The major issues were;

a) keeping the spotted owl from becoming extinct (as well as other possibly endangered species that used its habitat); and,

b) ensuring wellbeing of the rural infrastructure—woods workers, loggers, millworkers, and the dependent infrastructure of teachers, shopkeepers, law enforcement, etc.

Two distinct alternative solutions were available to President Clinton:

- Stop logging in large forest areas. The result would keep the current spotted owl habitat, except for that lost by windthrow; but would not increase the habitat nor sustain the rural people;

- Stop logging in complex and understory forest structures, but remove (a.k.a. thin) some trees in the dense (stem exclusion) structure both to accelerate growth toward future “complex” structures for spotted owls and associated species and to maintain timber supply and productive jobs to sustain rural communities.

The first alternative was chosen by President Clinton despite a U.S. court ruling that the choice was biased and therefore illegal. (President Clinton’s scientific team had excluded scientists knowledgeable about the new scientific paradigm.) As predicted, the rural communities became impoverished with the associated social strife (suicides, families breaking up, children becoming delinquent, etc.).

2) Healthy forest/forest fire issue: A report in the 1990’s to the U.S. Congress concerning “Forest Health” warned that the forest fires were likely to increase unless thinned because of the large areas of “dense” (stem exclusion) forests. Several alterative actions and their consequences were presented.

The report was prepared by a panel of University forestry professors and other professionals. It was delivered as a three-volume printed report and in oral hearings of the U.S.Congressional Agriculture Committee.

The committee suggested thinning the forests to reduce the stress on the densely growing trees, reduce the fire danger, provide primary employment to rural communities, provide wood, and make the forests safer for forest residents and visitors.

Environmental groups objected, with some advocating to let the forests burn because, “burning forests are natural.”

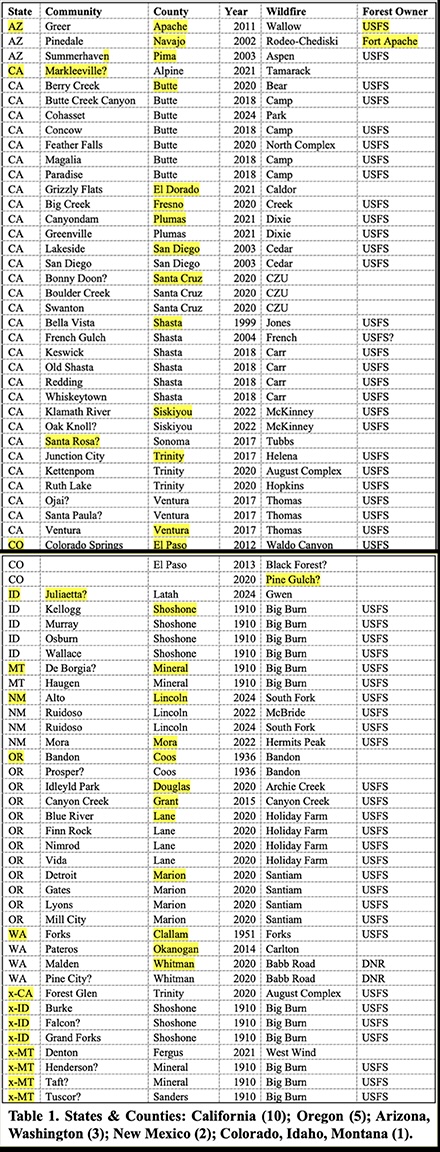

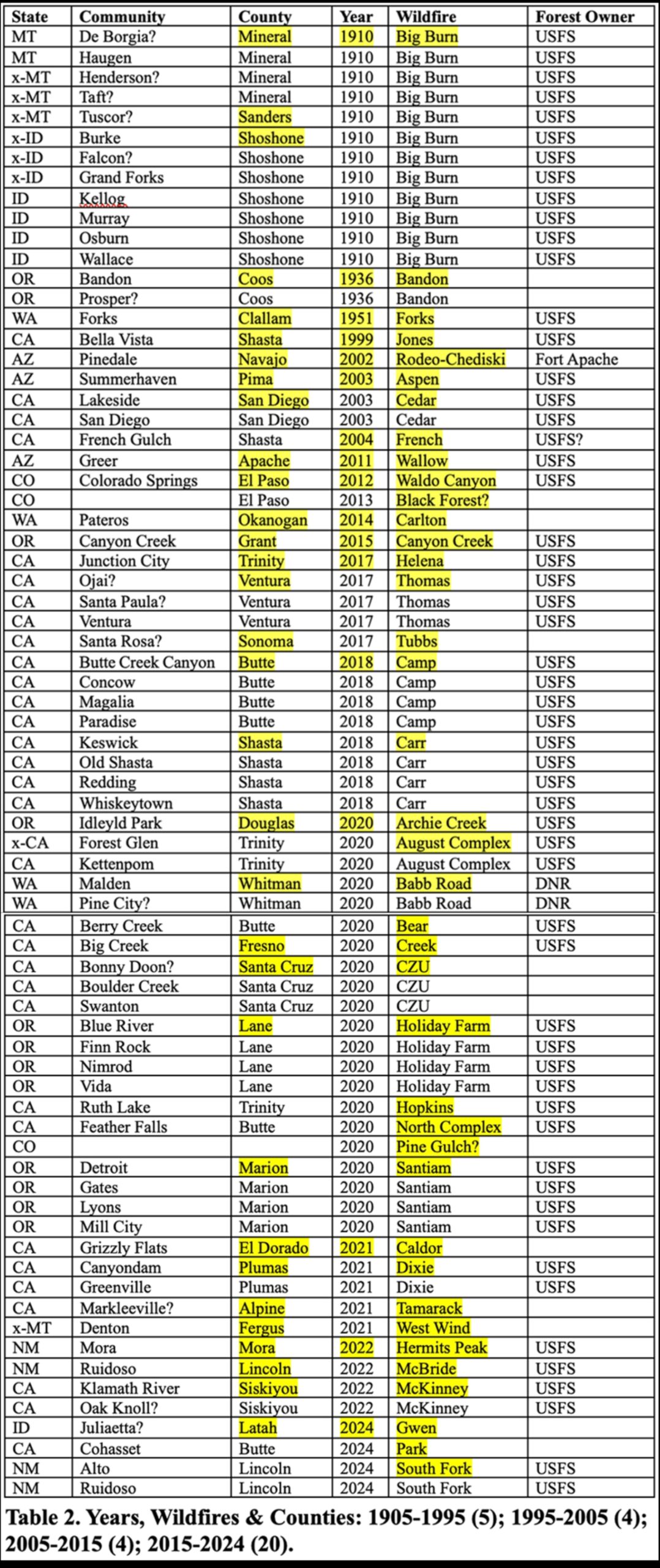

The lack of aggressively thinning the dense stands led to large forest fires with loss of homes in the subsequent decades (2000 to 2020).

3) Recent environmental guides on some Montana forests stipulate that grizzly bear populations need to be much higher.

Currently, these lands contain a large amount of dense (stem exclusion) structure and very little open (stand initiation) and savannah structures because of two actions:

- past logging and uncontrollable fires that created large openings that grew to dense stands;

- exclusion of low intensity fires that would have thinned the dense forests to create more savannah structures. Bears live in openings and savannah structures where they can feed on vaccinium berries, clover, and other tuber species.

There is currently an effort to determine if thinning the dense forests can increase grizzly bears in these forests by allowing the greater sunlight to provide more herbs as food for the bears.

4) The recent beginning of a focus on the value of rural people. During the past few decades, rural forestry people were discounted or vilified. (See book: Broken Land, Broken Trust; see also movie “Fern Gully.”)

Recently, however, the issue may be starting to shift to respecting and appreciating these people’s value. See: Editorial in Nature, 15 May, 2024: “Forestry social science is failing the needs of the people who need it most.”

Rich nations’ fixation on forests as climate offsets has resulted in the needs of those who live in or make a living from these resources being ignored. A broader view and more collaboration between disciplines is required.