This AP article, which ran in most all Montana newspapers, caught my eye yesterday. I’d like to use it to point out a few things related to wildfires.

The title of the article is “State’s wildfire season second-biggest so far this decade.”

For starters, what’s sort of bizarre, is that the reporter only looked at a 6 year time frame (since 2010) not a decade.

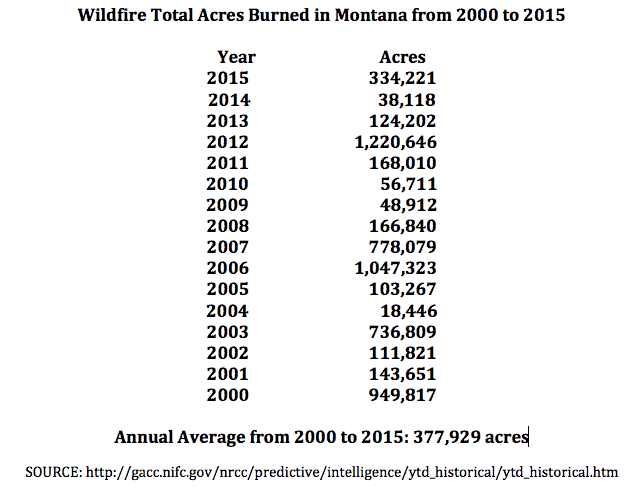

When you dig deeper into the article you see that so far the 2015 wildfire season in Montana (which is quickly coming to a close on account of some weather events last week, as well as more snow and rain coming this week) has only burned 27% of the total acres burned in the 2012 wildfire season in Montana (334,221 acres in 2015 vs 1,220,646 acres in 2012).

Wanting to know more I spent about 30 minutes at this link via the Northern Rockies Coordination Center, which ironically was provided to me by the reporter when I asked him some detailed questions. Why the reporter was unable to apparently spend a few minutes checking out these statistics is a mystery.

So, I copied down all the wildfire burned acres totals in Montana from 2015 going all the back to 2000 (see chart above).

What quickly becomes apparent is the wide range of acres burned from year-to-year.

In fact, based on these numbers a more accurate frame for the AP story about the 2015 wildfire season might have been that so far Montana has seen a little less than the average acres burned going back to 2000.

It’s also worth pointing out that another way of looking at this year’s wildfire season in Montana is that, to date, we’ve only burned 27% to 45% of the acres burned in Montana during the wildfire seasons of 2012, 2007, 2006, 2003 and 2000.

While technically the title of the article, and framing of the story is correct, I’d put forth that there are much more accurate (although, perhaps less ‘flashy’ and ‘sensationalistic’) ways of looking at Montana’s 2015 wildfire season.

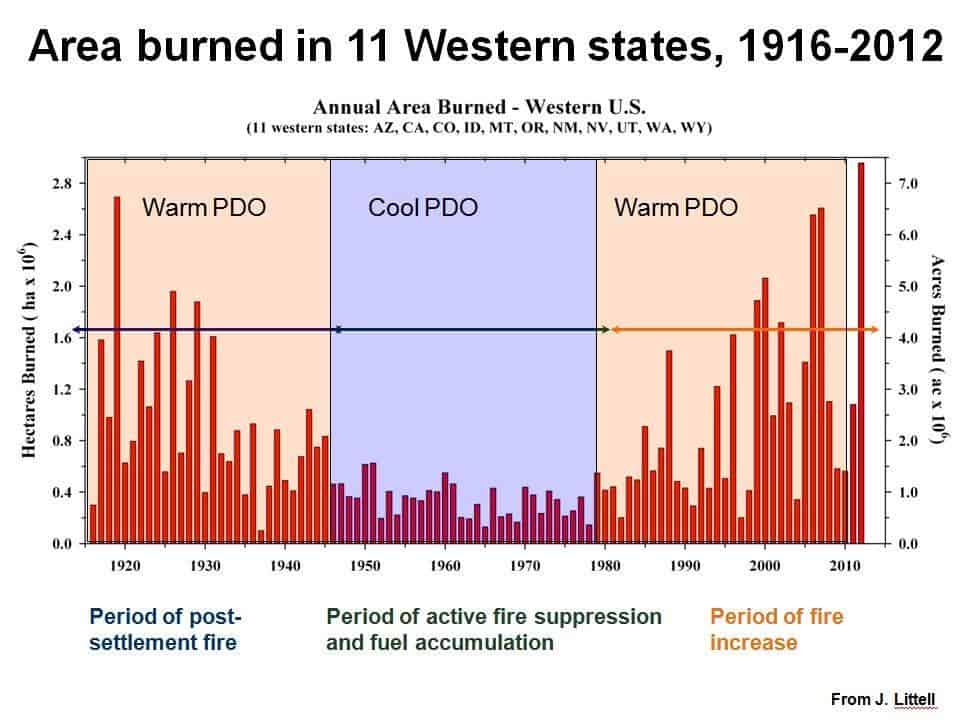

Looking at the chart going back to 2000 another issue that becomes apparent, to me anyways, is that there appears to be no correlation whatsoever between the total burned acres and the amount of national forest logging and/or national forest lawsuits; although that fact certainly doesn’t stop some from within the logging industry or politicians from trying to always make that case.

Of course, it goes without saying that weather conditions such as drought, heat and wind have a huge impact on the total number of acres burned, as do long-term climate factors. Another issue is total number of ignitions (whether by people or dry lightening storms) and what part of the state the ignitions occur in (i.e. eastern grasslands vs western forests).

I’ve lived in Montana since 1996 and have to say that compared with my home state of Wisconsin it always seems very dry out here, whether or not we are technically in the grips of drought, which we certainly are in now.

So perhaps ignitions are even more of a key factor in the total number of acres burned in Montana in any given year, rather than drought.

I also suspect that wind plays a huge role in all of this. Really, the common denominator in all major wildfires is wind. No wonder some people find wind so annoying.

This information is not meant to discount specific experiences communities, homeowners or citizens have had with wildfires this year, but just serves as a bit of important, fact-based information and context, at least as far as Montana’s wildfire season goes.

As I’ve said before, information like this is especially important in the context of recent statements (and pending federal legislation) from certain politicians blaming wildfires on a lack of national forest logging or a handful of timber sale lawsuits.

If politicians are going to predictably use another wildfire season to yet again weaken our nation’s key environmental or public lands laws by increasing logging (including calls by politicians like Montana’s Rep Ryan Zinke for logging within Wilderness Areas) then the public should at least have some facts and statistics available to help put the wildfires in context.