What follows is a press release from Friends of the Clearwater.

Moscow—In an ongoing effort to commemorate the 50th Anniversary of the Wilderness Act, Friends of the Clearwater released a report today that critically examines the Clearwater Basin Collaborative (CBC)Agreement and Work Plan. If enacted by Congress, the agreement would put into place provisions that are incompatible with the Wilderness Act, potentially causing a ripple effect throughout the entire National Wilderness Preservation System, too. A copy of the analysis can be found at friendsoftheclearwater.org.

“If passed in its current form, the legislation could have a detrimental effect on the entire National Wilderness Preservation System,” said Gary Macfarlane, Ecosystem Defense Director for Friends of the Clearwater. “Citizens need to be aware that there is a group proposing legislation that would designate a minimal amount of supposedly new Wilderness in the Clearwater basin of Idaho, but that proposal contains provisions incompatible with the letter and spirit of Act. That would be “wilderness” in name only.

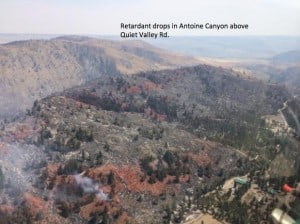

The Clearwater Basin Collaborative Agreement and Work Plan could give the Idaho Fish & Game Department motorized access to manage wildlife in newly designated Wilderness.

“The CBC Agreement and Work Plan could give the Idaho Fish & Game Department authority to land helicopters and use motorized equipment in newly designated Wilderness,” said Brett Haverstick, Education & Outreach Director. “This equates to the department running a game farm in what is supposed to be untrammeled and wild.”

Another red flag for conservationists is that the agreement contains language that would grant special rights to commercial outfitters in newly designated Wildernesses. These are rights not enjoyed by the general public or outfitters elsewhere in national forests, let alone Wilderness. Commercial enterprises are generally banned in Wilderness and only a narrow provision for outfitting is allowed so long as the outfitting is necessary and proper.

“As proposed, the potential legislation would grant special rights to outfitters, allowing them to maintain existing permanent structures in newly designated Wilderness, plus give them veto authority over the Forest Service if they are requested to relocate their camp due to resource damage or for any reason,” continued Brett Haverstick. “The Wilderness Act prohibits commercial services but makes a narrow exception for services like outfitting only as long as it is necessary and proper. Permanent structures, which are prohibited, and special rights for outfitters are neither necessary nor proper in Wilderness.

The Clearwater Basin contains 1.5-million acres of unprotected roadless wildlands. A study in 2001 (Carroll, et al.) noted that the basin contains the best overall habitat for large carnivores in the entire northern Rockies, including Yellowstone National Park and the Canadian Rockies. The group also claims that current management direction under the 1987 Clearwater National Forest Plan (as amended by the 1993 lawsuit agreement) provides far better protection than the proposed Agreement and Work Plan, even though the agreement also covers most of the Nez Perce National Forest.

“Out of 1.5-million acres of roadless wildlands, the CBC Agreement and Work Plan would designate 20% of the roadless base as Wilderness, or roughly 300,000-acres,” said Gary Macfarlane. “Areas such as Weitas Creek and Pot Mountain have been completely ignored for Wilderness. Current management direction on the Clearwater National Forest, as per the lawsuit settlement agreement, has over 500,000 acres managed as recommended wilderness.”

The CBC proposal also includes two special management areas, approximately 163,000 acres, with some protection, though one area would be open to some motorized use. Haverstick noted, “Ironically, the proposed western West Meadow Creek special management area on the Nez Perce National Forest, seems to have better overall protection than the proposed wildernesses because this proposal has provisions that would weaken wilderness protections.”

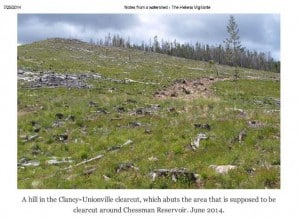

In addition, the Friends of the Clearwater report notes that the CBC proposed protection for wild and scenic rivers would be less than that proposed by the Forest Service and also the CBC agreement would lead to substantial increases in logging, even though many streams are not currently meeting water quality standards.

Gary Macfarlane concluded, “This agreement is a giant step backwards and a net loss for the roadless wildlands of the Clearwater Basin. On the 50th anniversary of the Wilderness Act, this special place deserves much better.”