I am reposting this article from two years ago, but in its entirety, rather than as just a link. The main reason for reposting this is because of current discussions regarding “forest restoration” by newer participants on this blog, but it is also a good illustration as to how much the discussion dialogue and civility has improved here since that time. All of the photographs are by me except the cover photo, which is by Nana Lapham of Oregon Websites and Watersheds Project, Inc. The maps are by me and by Terrie Franssen of the Douglas County, Oregon Surveyor’s Office. The circulation of Oregon Fish & Wildlife Journal

is about 10,000: mostly rural families and forestry-related businesses and urban outdoor sportsmen. It is not a peer-reviewed journal, but rather a popular magazine intended for “furthering the concept of multiple-use of our lands for more than 30 years.” WordPress does a poor job of duplicating illustrations from PDF files, so clearer versions of these maps and photographs can be found here: http://www.nwmapsco.com/ZybachB/Articles/Forest_Restoration_2012/

Actively managing our western forestlands on a landscape-scale can immediately create thousands of rural jobs, greatly reduce catastrophic wildfire risks and damages, return millions of dollars to our state and federal treasuries, increase native wildlife populations, fund our rural schools, roads, and libraries, and make our forests and grasslands safer and more beautiful than ever before. Seriously.

Western forestlands have never been in worse shape: millions of acres of dead and rotting trees; thousands of miles of abandoned and barely maintained roads; record wildfires becoming larger, deadlier, and more destructive by the year; hundreds of artificially impoverished rural communities; and endless litigation preventing the use of resources we need to sustain our lives and our economy.

There are a number of reasonable ways to resolve these problems; a long-term commitment to active forest restoration and management seems to offer the most immediate benefits to both people and wildlife, and is the likely route to economic sustainability as well.

What is forest restoration, why is it needed, and how is it done are the questions addressed in this article. Two examples of current forest restoration projects are profiled to help answer these questions, and illustrate how these types of programs can be immediately implemented across the landscape to the benefit of neglected forests and depressed timber-producing communities throughout the West.

What is Forest Restoration?

The process of forest restoration is focused on returning an area to one reflecting desired past conditions, it is critical to understand a) what conditions were actually like in the past, and b) which of those characteristics (if any) should be restored or preserved for the future.

For the past 10,000 years and longer, Native Oregonians have used plants and animals for their own purposes: principally for food; shelter; fuel; and fiber products, such as clothing, basketry, musical instruments, canoes, ropes, and weapons. Fire was used for a wide range of purposes: for cooking, heating, and lighting areas around homes and campgrounds; for rejuvenating berry patches and harvesting fields of grain; for hunting game by systematically setting vast tracts of land on fire.

Man is the only animal that can use fire, but he is not the only animal that benefits from it. The expert and judicious use of fire across the ancient landscapes of Oregon resulted in the stable patterns of forests, woodlands, vast prairies, wetland meadows, brakes, balds and berry patches encountered by Oregon Trail immigrants in the 1840s and 1850s. Elk, deer, songbirds, fish, squirrels, migratory fowl, and other animals that populated these environments were documented by many of the new residents.

Forest restoration, means restoring people to the land, whether in the woods, along a river, or walking through a town. Restoring people to the land also supposes restoring fire to the land; fires set by people, not lightning.

Upper South Umpqua Project: Considering Past Conditions is Step 1.

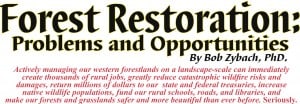

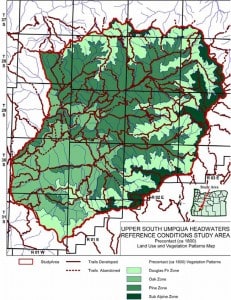

The maps shown in this article represent a critical step in the forest restoration process – a determination and documentation of likely past conditions for areas being considered for restoration. Whenever we plan to restore something, it is important we understand the conditions that existed in the past.

The “Upper South Umpqua Headwaters Precontact Reference Conditions Study” focused on characterizing a significant portion of the Umpqua National Forest in Douglas County, as it likely existed in 1825. The study area is slightly more than 230,000-acres in size and extends from the crest of the Cascade Range westward to the confluence of Jackson Creek with the South Umpqua River. The map shows the location and composition of forest type patterns as they likely existed in the study area 200 years ago. Each of the subsequent four photographs documents a typical example of each of the four forest types, and illustrates potential forest management actions needed to restore and maintain desired future conditions.

Map: Forest Type and Trail Patterns, 1800-1825

Map: Forest Type and Trail Patterns, 1800-1825One of the basic purposes of forest restoration is to reduce wildfire risk and damages. The method for achieving this in overstocked stands of conifers is to significantly reduce their biomass (“fuel load”) and open up the tree canopies (“thinning”) as they existed in earlier times, when catastrophic-scale crown fires were uncommon occurrences. On federal lands this is referred to as an “FRCC 1” condition.

The Upper South Umpqua Project was initiated by Douglas County Commissioner, Joe Laurance, to consider the possibility of restoring degraded local forestlands to presettlement condition. On July 15, 2010, he testified to a Congressional subcommittee of The House Natural Resources Committee in Washington, DC:

“Fire Regime Condition Class (FRCC) 1 is similar to the forest which European explorers first found here. That forest had been modified by fire for more than six thousand years to provide the native inhabitants with what were then life’s necessities. These included abundant wild game from the most productive and diverse wildlife habitat ever known on this continent. Similarly, the regular burning of competing vegetation permitted propagation of nut bearing trees and other food producing plants. Additionally, the historic “Healthy Forest” promoted pristine rivers, streams, and lakes that provided an abundant harvest of fish and waterfowl. Within FRCC 1 the risk of losing key ecosystem components to fire is low, while vegetation species composition, structure, and pattern are intact and functioning within the natural historic range.”

Research methods used to determine and document 1825-era forest conditions in the study area included extensive use of General Land Office survey maps and notes, historical maps and photographs, field plots, oral history interviews, literature reviews, archival research, and over 5,000 GPS-referenced digital photographs. This latter method documented the location and extent of remaining old-growth (pre-1825) trees in the study area, in addition to documenting persistent patterns and patches of such traditional cultural food and fiber plants as camas, fawn lilies, cat’s ears, huckleberries, hazelnuts, chinquapin, tarweed, serviceberry, wokas, bracken fern, thimbleberries, and salal.

Historical research has given us the map shown: a generalized depiction of likely forest conditions in the study area during the 1800-1825 time period. The following four photographs represent current typical conditions within each of the four forest types (or “zones”) shown on Map 4. The large size and wide spacing of the older trees in the photographs can be gauged by the “human scale” used to measure them: Nana Lapham, long-time forest science research assistant of NW Maps Co., did much of the field work on this project.

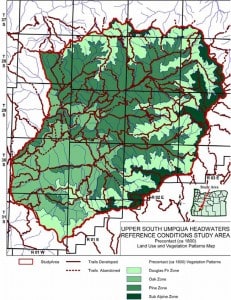

Photograph 1: Oak Type. Former oak and pine savanna.

Photograph 1 shows relict trees from an oak and pine savanna that was developed and used by native residents for hundreds or thousands of years. These areas were tended by constant gathering of fuel, acorns, and pine nuts from the trees and regularly tilling and/or burning the surface area to manage understory crops, such as camas, tarweed, hazel, and beargrass. Notice how Douglas-fir have invaded the area in the past 100+ years, threatening the survival of the few remaining old-growth oak and pine.

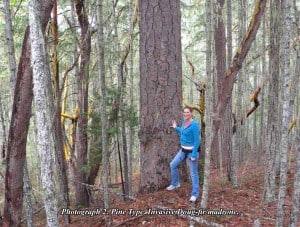

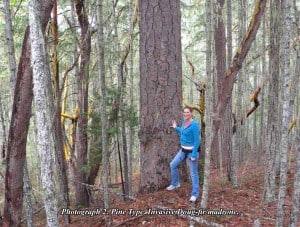

Photograph 2: Pine Type. Invasive Doug-fir/madrone.

Photograph 2: Pine Type. Invasive Doug-fir/madrone.Photograph 2 is a typical condition found throughout the former Pine Type in the study area. Again, these areas were maintained by regular prescribed fires in precontact time, and continuous canopy of fine, pitchy fuels. A crown fire under these circumstances would likely kill all of the trees in this picture, including the old-growth.

Restoring this savanna would entail removing the Douglas-fir, before they smother the remaining old-growth, removing the surface fuels that have built up around the bases of the oaks and pines, and reintroducing the understory plants and regular burning practices that created and maintained savanna conditions in the first place. There are thousands of acres similar to this throughout the study area, with invasive Douglas-fir slowly killing the established old-growth and creating potential crown-fire conditions by developing a are now being threatened by thousands of invasive Douglas-firs and madrone.

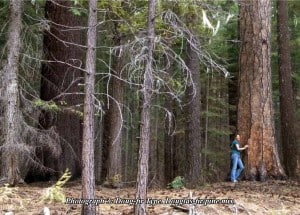

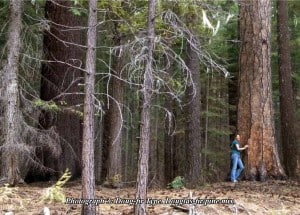

Photograph 3: Doug-fir Type. Douglas-fir/pine mix.

Photograph 3: Doug-fir Type. Douglas-fir/pine mix.

Photograph 3 shows the 1825 Douglas-fir Type, which still contains scattered old-growth sugar and ponderosa pine; species which may have dominated this type in the Indian era. Restoration provides the best option for prolonging the lives of these historic trees, too.

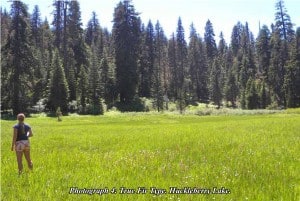

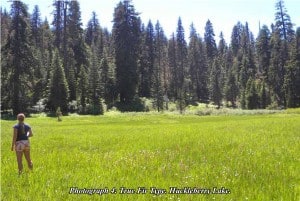

Photograph 4: True Fir Type. Huckleberry Lake.

Photograph 4: True Fir Type. Huckleberry Lake.

Photograph 4 is a picture of Huckleberry Lake, in the high elevation True Fir Type. The “lake” is now a wetland prairie. This area used to be a portion of a major huckleberry gathering complex, equally accessible to Indian families living in the Rogue River and South Umpqua basins before these plants were shaded out by the invading conifers. The taller trees in the background represent larger diameter, older trees likely dating to the 1600s and 1700s; the vast majority of trees, though, having established themselves after the mid-1800s and throughout the 1900s.

The common theme throughout these maps and photographs is that tens of thousands of acres of old-growth oak, pine, Douglas-fir, red cedar, and other conifers exist throughout the study area are in need of immediate attention, if they are to survive. The same problem exists for the scattered patches of huckleberry, camas, tarweed, and native grasses that still persist. A forest is, ideally, composed of many facets, housing many different types and species of plants and animals. Those are the types of attributes that used to define these lands, and the same types that can be restored and maintained for future generations of people and wildlife.

Jims Creek Project: Make a Choice and Then Do It is Step 2.

The second step to forest restoration, is to determine what future conditions are desired and to begin actively restoring and/or maintaining those desired conditions across the land. An excellent example of this step is the Jims Creek forest restoration project on the Middle Fork Willamette Ranger District, which is in the process of completing an initial 400-acre “demonstration project” portion of a 25,000-acre plan.

The Jims Creek project has demonstrated the feasibility, profitability, and general benefits of conducting landscape-scale forest restoration projects on federal forestlands, but it is also a good example of how much time can be spent in putting these projects together, as well as the ease and quickness with which they can be stopped by adversarial legal actions. This project was initially conceived by a local US Forest Service forester/project manager, Tim Bailey, who then spent the better portion of the next ten years shepherding his vision through the myriad public meetings, scientific reviews, committee presentations, promotional tours, and other hurdles needed to get things underway on the ground.

Photograph 5: Tim Bailey and elk herd on Jims Creek site.

Photograph 5: Tim Bailey and elk herd on Jims Creek site.Picture 5 shows Bailey in front of a portion of the Jims Creek Project in 2010. This area had already been treated by removing most of the invasive conifers established during the past century, and by broadcast burning the ground so as to remove excess litter and logging debris. Note the scattered trees that have been left behind: widely spaced pine of several different age groups, from seedlings to saplings and second-growth to old-growth. Also note the small herd of elk grazing directly above Tim, near the crest of the hill.

Photograph 6: Close-up of 15-16 elk in restored prairie.

Picture 6 is the same herd of elk as the previous picture, seen through a zoom lens. The small charred stumps and large woody debris in the foreground will soon rot away or be consumed in the next few surface fires. The reddish-brown pattern is bracken fern, a plant harvested in large quantities by many Oregon tribes for its starchy roots and asparagus-like “fiddleheads” that grow in the spring. In a few more years, with a few more broadcast burns, this area will appear very similar to what it must have looked like hundreds of years ago.

Additional restoration has been halted at this time due to an infestation of red tree voles (“tree mice”) that accompanied the migration of Douglas-fir trees into the project area during the past century. These rodents are protected against logging under a federal “survey and manage” regulation, despite the fact they are not a threatened or endangered species.

This type of work stoppage, based on new federal regulations and litigation initiated by environmental organizations, has become the main difficulty in beginning and completing forest restoration projects in Oregon and throughout the West. Of the 25,000 total acres of this project within the Middle Fork Ranger District, 7,000 acres are privately owned and managed for maximum timber production; more than 7,000 acres have been classified as spotted owl habitat; approximately 7,000 acres are in remote areas that would likely include the “taking” of spotted owls; and the remaining 4,000 acres are populated with regulated tree voles. A river flows through the project area that contains two listed fish species and “there is a perception on the part of the regulatory agencies that this type of restoration work can have a negative effect on fish.”

Despite these hurdles, there is a lot of work needing to be done and a lot of people wanting to do it.

Conclusions

Forest restoration projects should be conducted on a landscape-scale basis in order to be effective biologically, aesthetically, and economically. Project boundaries should include sufficient commercial materials to treat the project area and show a profit. Profitable and beneficial actions are sustainable on a long-term basis, as we have learned from more than 10,000 years of forest history in this region.

The actions needed to restore our forests to earlier, more desirable conditions would create thousands of jobs for decades, jobs to make the best use of our resources, protect our old-growth and its wildlife, and greatly reduce the likelihood and severity of wildfire when they did take place. Based on my own experiences and observations, I think there are four things that must be in place for forest restoration projects to be successful on a long-term basis:

1) Areas slated for restoration should include sufficiently broad boundaries and specifications to allow projects to be profitable;

2) Restoration projects should be landscape-scale (25,000 to 250,000 acres) in size in order to be economically efficient and biologically effective over time;

3) Local residents and businesses should be in strong support of restoration projects, and be given access to all information that develops during the process;

4) Local project managers should be knowledgeable and capable of communicating scientific, technical, and political aspects of a project to local citizens.

I remain certain that the adoption of these practices, as defined, would have many immediate and positive effects on forest health, old-growth preservation, endangered species protection, rural economies, international trade balances, and many other economical, ecological, cultural, historical, aesthetic and recreational values associated with Oregon’s forests.

The degradation, destruction, and loss of our federal forests and grasslands to wildfire, bugs, and disease will continue to escalate so long as we continue our current path of passive avoidance and neglect. Restoring our Nation’s forests means restoring people – in part, as active managers – to our lands. The benefits for doing so have been listed; the impediments to getting started have been largely self-inflicted, are almost entirely political (rather than scientific or humanitarian), and can be readily surmounted, given effective leadership or common outcry. The best time for doing something is now.