Thanks to readers sent in this fascinating WaPo story Trees are moving north from global warming. Look up how your city could change. The graphics and mapping, as so often happens, are way better than the assumptions behind them.

There’s much to question there. For one thing, the article is talking about hardiness maps and so “people planting trees”. Beware of English in headlines! To most of us, “moving” is different from “being moved”. Active versus passive.

Modeled vs. Observed

Another obvious problem is that it’s not exactly clear that it’s all modeled changes. So not, “moving” but “being moved on the basis of models.”

In fact, modeled results are better than observed results, according to this reporter (!), who is admirably careful about being clear on modeled vs. observed.

Unlike the government’s official plant hardiness zones, which were released in 2012 and are based on temperature observations from 1976 to 2005, the projections shown here include a time range closer to the present day and allow for comparisons over time.

But my favorite topic, of course, is what the article says about tree adaptation. I’m not criticizing the reporter here. I also had trouble finding current experts; in fact it appears that forest genetics, like tree physiology, and forest entomology and pathology have become less cool over time, That’s just the way it is, universities have to keep up with trends of what’s cool or they won’t get funding. So no blame to anyone here, we are all parts of a system. But I will try to shed some light on this particular question.

Let’s think about this together and I’ll share some research.

Trees’ ranges adapt to change, but modern climate change is fast. Over the past century, the earth has warmed about 10 times faster than when it emerged from historical ice ages. With some difficulty, humans will adapt to global warming. For trees and the ecosystems that depend on them, adapting will be even harder.

Actually trees’ “ranges” don’t adapt to change, tree populations do. So let’s look at how fast climate change is happening.

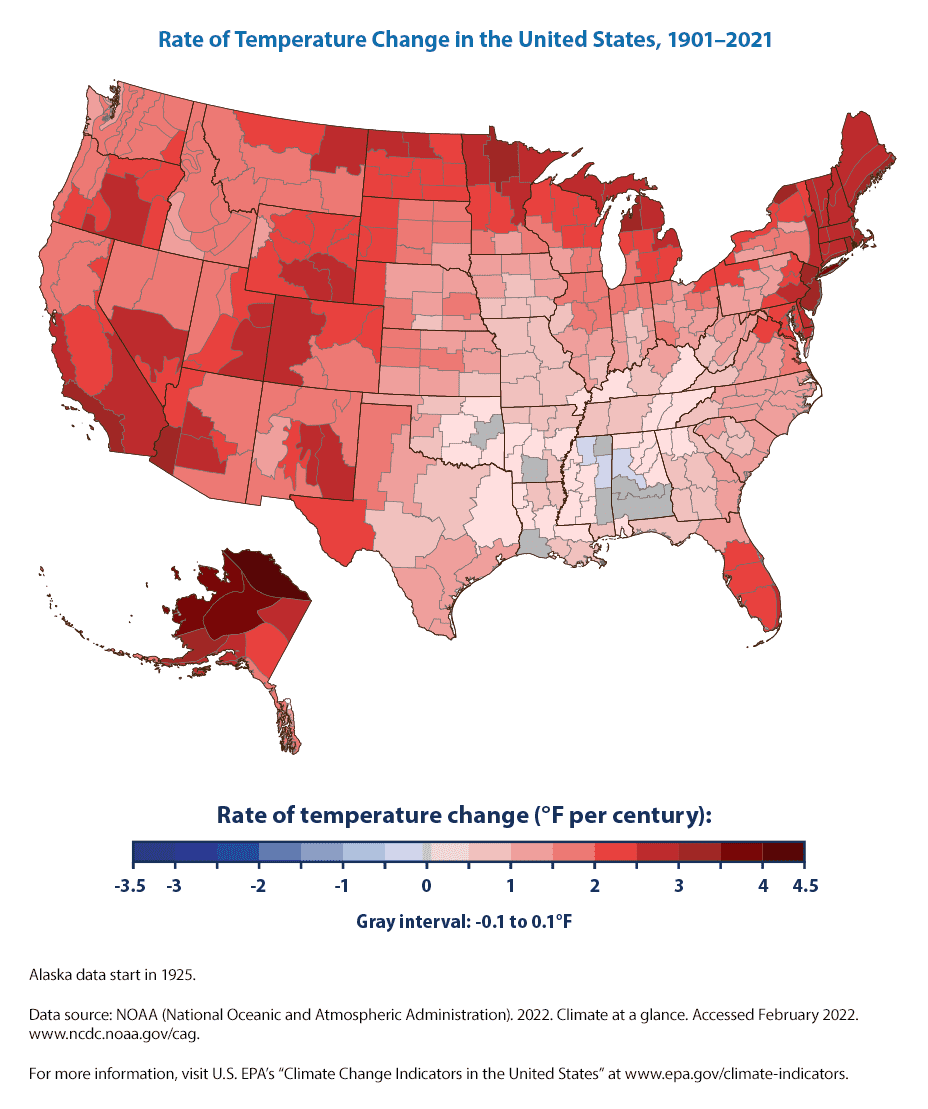

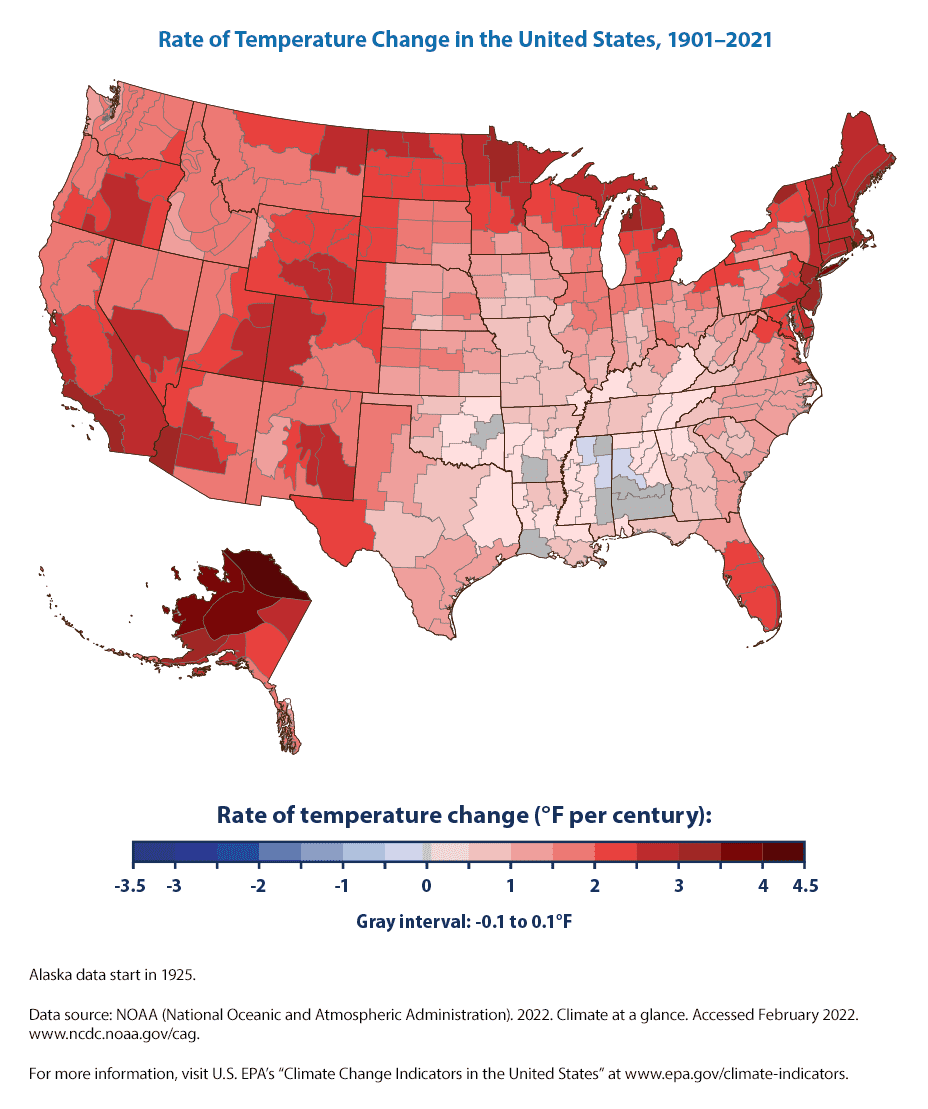

How fast? I found this on an EPA website. Note that they are observed differences over the last 100 years.

Since 1901, the average surface temperature across the contiguous 48 states has risen at an average rate of 0.17°F per decade (see Figure 1). Average temperatures have risen more quickly since the late 1970s (0.32 to 0.55°F per decade since 1979).

Some parts of the United States have experienced more warming than others (see Figure 3). The North, the West, and Alaska have seen temperatures increase the most, while some parts of the Southeast have experienced little change. Not all of these regional trends are statistically significant, however.

I thought the patterns over 120 years were very interesting, especially for the Southern US.

I thought the patterns over 120 years were very interesting, especially for the Southern US.

So there are two questions. First is “will the rate of change increase in the future?” .. I’ll ask some climate folks about that.

But the question that presents itself now is “are the observed differences too fast for tree species to adapt?”

We have historical evidence, and our own lived experience (of the elders among us) that there are many trees over 100 years old. In fact, the FS and BLM just mapped them for the MOG initiative! Which seems like evidence that not only populations of trees, but individual trees, have been able to survive the current rate of temperature change.

Caveat- average temperature is not particularly helpful to understand how tough trees find it to survive. The timing of frosts, cold extremes, season of drought and moisture, soil type, aspect, mycorrhizae, pathogens, competitors and so on..

The comments on the WaPo story point this out; also that more people seem to have problems with invasive pests and diseases than climate change. So what does looking at average temperature tell us? Probably not much.

I’ve seen them burn up. I’ve also seen them have tough times due to age (not a problem unique to trees- how do I know this?). For example, according to the Rocky Mountain LPP averages 150-200 years, thanks to this handy Fire Effects Information System (2003) compendium of info.

Silvics of North America also has good information. Biology hasn’t really changed.

Which reminds me of this box.

Time alone won’t kill a tree, but climate change might.

Unlike most living things, many trees can live indefinitely. There are trees among us today that took root before European settlers first arrived here. They have avoided fire, pestilence, drought and infestation, but some will not survive global warming.

Here’s what the cited paper says:

A preponderance of evidence has suggested that trees do not die because of genetically programmed senescence in their meristems (Mencuccini et al., 2014), and rather are killed by an external agent, either biotic or abiotic.

In the last 50 years, I’m not sure that I’ve observed climate change killing a tree, but certainly observed fires and bugs killing trees. And so, yes the 1980’s outbreak in Central Oregon may have been influenced by climate change (although at the time it was thought that was part of a natural disturbance cycle). Perhaps not so much bb outbreaks in the 20s and earlier.

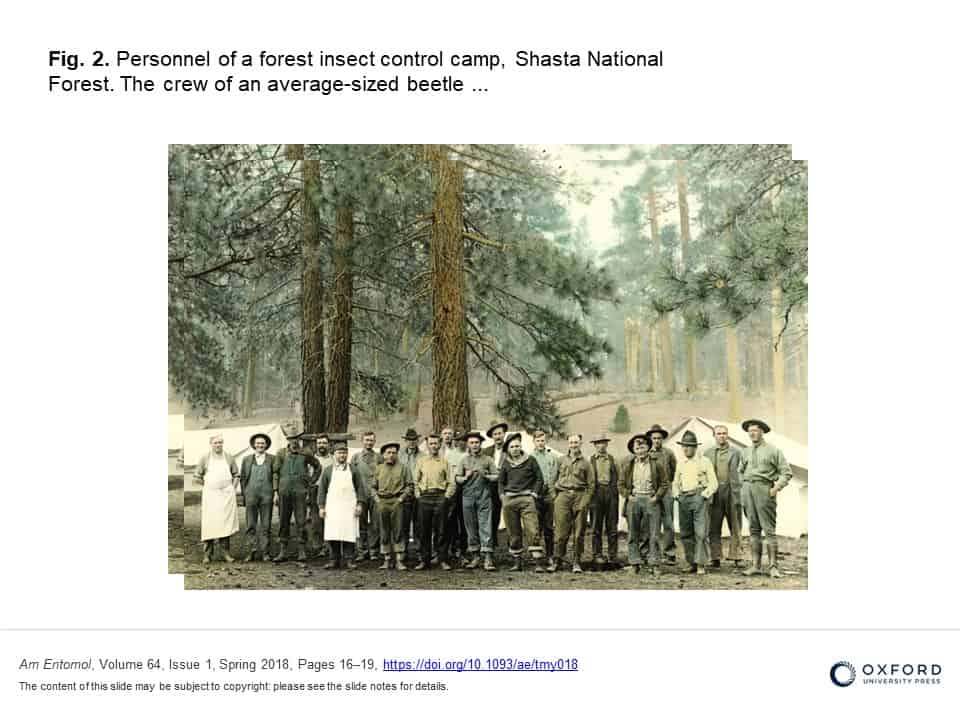

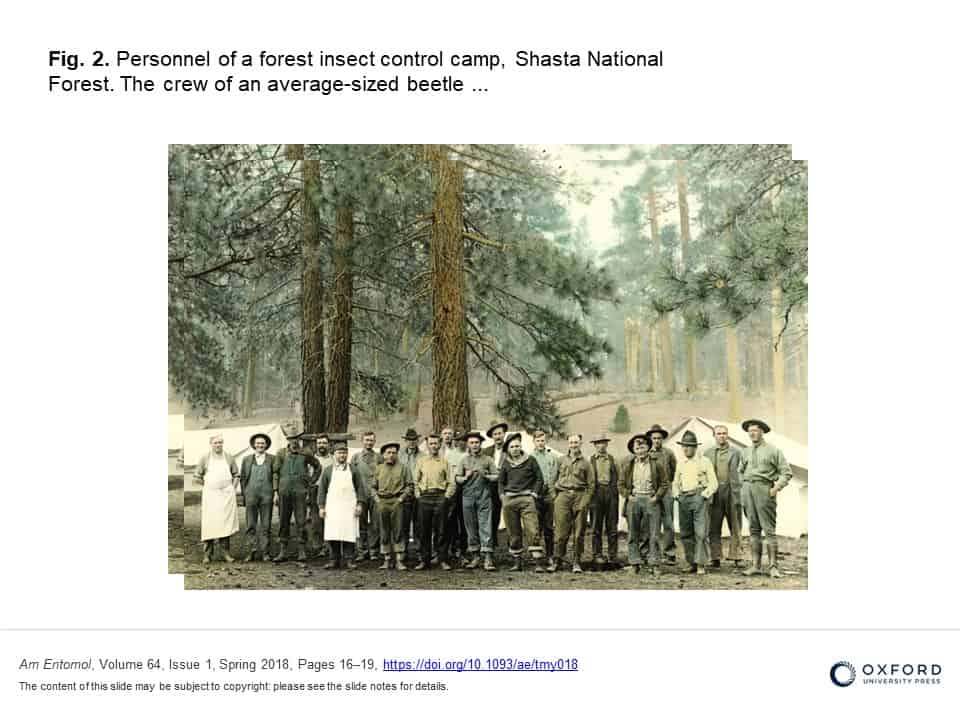

I found this fascinating paper on The Battle for Old-Growth Ponderosa Pine in Northeastern California: Efforts to Control the Western Pine Beetle in Remnant Old-Growth Stands During the 1920s

Fig. 2. Personnel of a forest insect control camp, Shasta National Forest. The crew of an average-sized beetle control camp consists of the foreman, cooks and flunkey, spotting crew, treating crews, and truck driver. Mess and bunk tents are shown in the background. Van Brewer Wells camp. Photo by J.E. Patterson, Oct. 1920.[/caption]

Fig. 2. Personnel of a forest insect control camp, Shasta National Forest. The crew of an average-sized beetle control camp consists of the foreman, cooks and flunkey, spotting crew, treating crews, and truck driver. Mess and bunk tents are shown in the background. Van Brewer Wells camp. Photo by J.E. Patterson, Oct. 1920.[/caption]

With terrific photos. Very, very cool.

The next post in this series will be on “some things we know about conifer genetics and adaptation.”