Washington, D.C.–(ENEWSPF)–November 17, 2011. On the heels of a landmark Tenth Circuit Court of Appeals decision upholding the 2001 Roadless Area Conservation Rule, a broad group of senators and representatives introduced legislation today to make sure the administrative rule remains the law of the land—locking in protections for 58.5 million acres of America’s wildest and most pristine forests and waters for generations to come.The Roadless Area Conservation Act, sponsored by 20 Senate and 111 bipartisan House co-sponsors, will confirm long-term protections against damaging commercial logging and road-building for vulnerable wildlands on 30 percent of the 193-million-acre National Forest System, shielding our Roadless areas from the political whims of future administrations.

This legislation highlights the strong congressional support for protecting America’s unique legacy of wild forests, despite a decade’s worth of attacks from an anti-environmental faction of Congress aiming to rollback Roadless protections. This legislation will also ensure that our Roadless protections are implemented across the nation—without exception.

Uncategorized

FS Improves Ranking in Best Places to Work

Here’s the link to the study.

New FS Fall Colors Website

It’s that magical time of the year.. check it out here.

Lawsuit over Seeley timber sale reveals split among environmental groups -Missoulian

Thanks to Terry Seyden for this contribution

Lawsuit over Seeley timber sale reveals split among environmental groups

By ROB CHANEY of the Missoulian | Posted: Tuesday, September 20, 2011 6:15 am | (3) Comments

A lawsuit challenging a timber sale north of Seeley Lake shows either the U.S. Forest Service can’t follow the law or some environmental groups can’t agree to work together.

The Alliance for the Wild Rockies, Friends of the Wild Swan, Montana Ecosystem Defense Council and Native Ecosystems Council all sued the Forest Service over the Colt Summit Forest Restoration and Fuels Reduction Project on Friday.

The project would thin trees and remove roads on more than 4,000 acres between Lake Alva and Summit Lake along Montana Highway 83.The lawsuit has angered members of several groups who support a collaborative effort to achieve both commercial logging and habitat restoration in the Seeley-Swan area. The Colt Summit was one of the tests of the Montana Forest Restoration Committee’s ability to move forward without legal challenges.

“I tend to be on the side of the coin where, if you bring a lot of people who don’t think a lot alike and take time to learn about the projects, we collectively can come up with better ideas,” said Anne Dahl of the Swan Ecosystem Center, one of the project’s supporters. “I think the Friends of the Wild Swan and others are more leery of collaboration. There’s sort of a fundamental philosophy where we’re different.”

“There’s no provision in there that says if 80 percent of the people sign off on it, they don’t have to follow the law,” responded Michael Garrity of Alliance for the Wild Rockies. “They have to show it’s benefiting wildlife.”

The project affects 4,330 acres in an area known to be a major wildlife corridor. About 740 acres would be logged and thinned, including 137 acres of old-growth forest. Another 1,216 acres would have the understory cleared and burned. In some areas, 19 acres would be clearcut to improve visitors’ views of the Swan Mountain Range and 69 acres would get “shelterwood patch cuts” that mimic forest openings.The Forest Service would decommission 4.1 miles of road, turning a stretch of the Colt Summit Road into a snowmobile trail. Another 5.1 miles would be reconstructed and linked into the snowmobile network. After the five-year project is over, 28.4 miles of temporary and winter-haul roads would be decommissioned.

For weed control, crews would spray herbicide on 34 miles of roads in the area, as well as all logging and other work areas.

The area is also prime habitat for grizzly bear, lynx and bull trout. Dahl said in her tours of the project, she believed the changes would benefit threatened and endangered species.

***

But the lawsuit alleges the Forest Service failed to take those animals’ needs into account when it planned the project.

Sara Jane Johnson was a Forest Service wildlife biologist before she became director of the Native Ecosystem Council. In a statement, she argued that removing beetle-killed trees hurt habitat more than helped it, because it took away nesting areas and cover used by everything from woodpeckers to lynx and grizzly.

The lawsuit also argues the Forest Service was supposed to perform a full environmental impact statement and evaluate how it fares under the National Forest Management Act and National Environmental Policy Act.

“Why do we win 85 percent of our lawsuits?” Garrity asked rhetorically. “We sued the Forest Service more than any other environmental group in the country and we won more than any other group. We raise the same issue every time they log on grizzly bear habitat because they have the same problem.”

University of Montana College of Forestry and Conservation Dean Jim Burchfield was part of the Lolo Restoration Committee and reviewed the Colt Summit project for inclusion in the Southwest Crown of the Continent Collaborative Forest Landscape Restoration Project proposal. That was one of 10 forest stewardship projects nationwide to receive funding from Congress last year.

“In my view, the Colt Summit project is about seeing how people with very different views of management priorities can come up with a project,” Burchfield said. “To fight the timber wars over every single timber sale is really counterproductive to the interests of most Montanans. There was an effort to be very careful in the development of that sale. They were looking at the most controversial areas and making sure all the laws and regulations were adhered to.”

Garrity disagrees.

“On this timber sale, we haven’t had a worse timber sale meeting,” he said. “They didn’t listen to anything we said. They just told us, ‘We’re fully funded on this and we’re pushing forward.’ ”

“There were other ones up there, and we didn’t oppose them,” Garrity continued. “One other sale was more in the urban interface, and we want them to do thinning near homes, not in critical lynx habitat. Over on the Flathead (National Forest), there’s a timber sale that adjoins this one. The boundaries touch, but they didn’t analyze for cumulative impacts. That’s one of the things they’re required to do.”

My question is with regard to this quote from Michael Garrity “There’s no provision in there that says if 80 percent of the people sign off on it, they don’t have to follow the law,” responded Michael Garrity of Alliance for the Wild Rockies. “They have to show it’s benefiting wildlife.” Does every action have to “show it’s benefiting wildlife?” is that a legal requirement?

Republican Revolution Proposed for County Payments

House Natural Resource Committee Republicans have floated a “discussion draft” of a county payments bill. It would phase out the current system of payments from the Treasury to be replaced by mandatory payments from national forest gross receipts. This scheme will surely cost the Treasury much more than the current payments.

The reason is simple. In most national forests, it costs the Forest Service substantially more than a dollar to produce a dollar of revenue. The bill tries to reduce these costs by eliminating most environmental laws. But the laws aren’t the source of the problem — the high-value trees have mostly been logged. The national forests, especially in the West, are not productive places to grow timber.

The bill would also create a new legal mechanism that allows counties to sue the Secretary of Agriculture to force him to spend whatever it takes to produce the necessary receipts.

The bill would mean the end of stewardship contracting in most places. No longer would the Forest Service afford to use timber value to purchase work in the woods. The counties’ mandatory revenue payments would soak up all the timber value.

Environmental groups will also blister the bill because it repeals NFMA, NEPA and the ESA. I don’t know why (as the courts have said it “breathes discretion at every pore”), but the bill even repeals the Multiple-Use Sustained Yield Act. And the bill exempts national forest logging and other revenue-generating projects from any and all review in the courts.

As a “discussion draft,” it is sure to engender a lot of discussion. But it is not a serious piece of legislation that will see the President’s desk in this Congress.

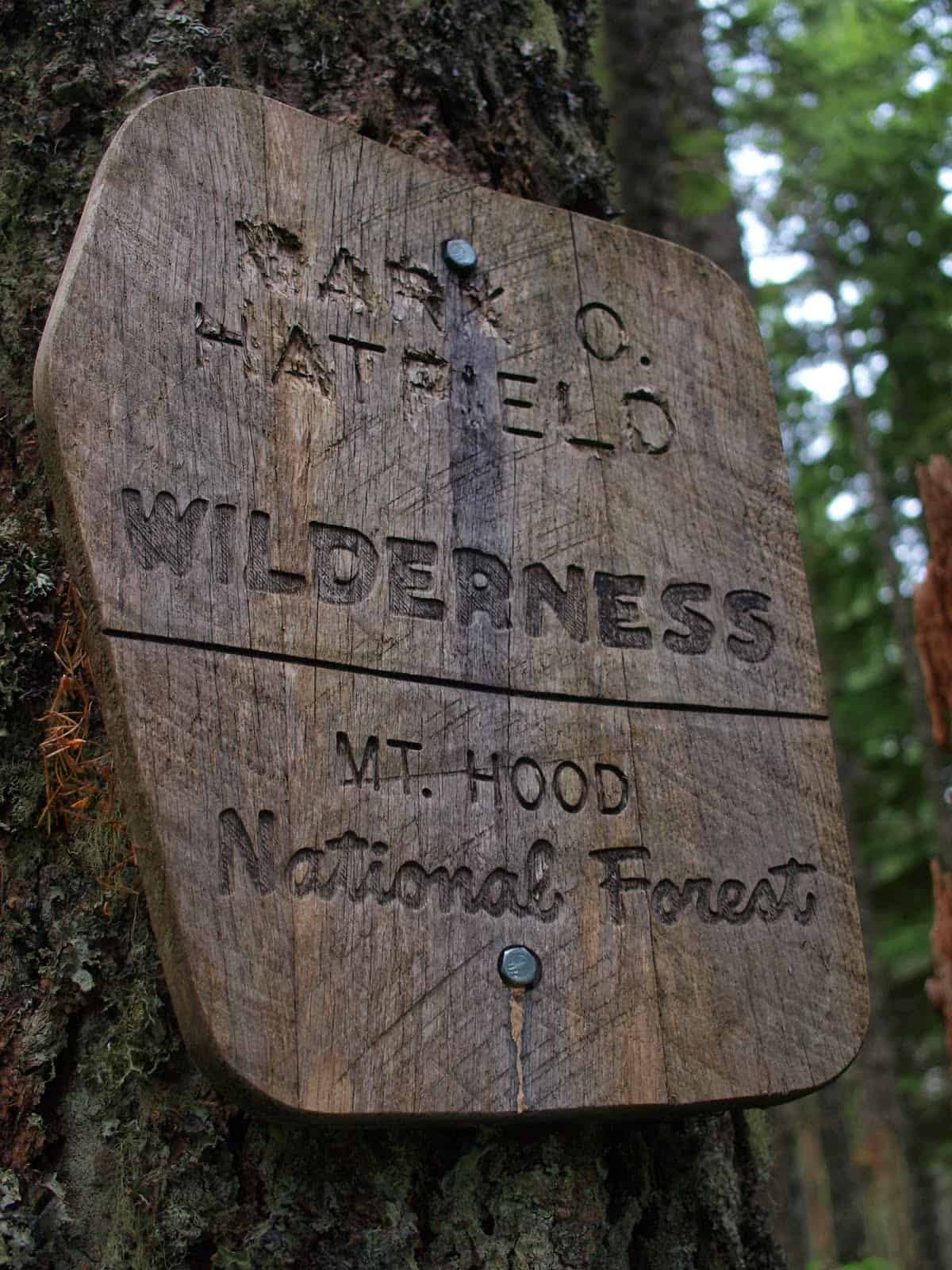

Senator Hatfield’s Forest Legacy

Oregon’s longest-serving senator, Mark Hatfield, died yesterday at 89. As a youngster, I remember my mother campaigning for Hatfield in his first election to the U.S. Senate (1967), notwithstanding her life-time Democratic Party affiliation. As Oregon’s governor, Hatfield had opposed the Vietnam War, and that was enough to earn my mom’s support. Later, as an adult, I got my own chance to see him at work.

The first time was during the Mapleton litigation, circa 1982. My employer, the National Wildlife Federation, sought to reform logging practices in the steep and erosion-prone Oregon Coast Range. For a generation, the Forest Service had paid little heed to its own scientists who warned that clearcut logging and roadbuilding would accelerate mass wasting and landslides. When environmental disclosure documents fabricated erosion calculations, we sued and won a court injunction stopping timber sales on the Mapleton Ranger District. Throughout the lawsuit and its aftermath, I made it a point to stay in constant contact with Senator Hatfield natural resources staff. Sure enough, the Senator used his Appropriations Committee chairmanship to attach a rider that allowed buy-back timber sales (sales returned to the government due to purchaser speculative bidding) to go forward, notwithstanding the court’s order. It was a measured legislative response (we had not sought to stop these sales in the first instance) to the beginnings of an inexorable reformation in Coast Range logging practices.

A couple years later, Hatfield presided over a fractured Oregon delegation as it passed the 1984 Oregon Wilderness Bill. His office vetted every roadless area included in the bill, which, among other things, gave Siuslaw coastal rainforests their first (and, so far, only) wilderness protection.

Although Hatfield did not have any great interest in forest or environmental policy — his scope was much broader — his last act as a legislator was the protection of Opal Creek’s ancient forests.

In today’s era when many elected officials seem less leaders than supplicants, Hatfield stood tall as a true Oregon statesman.

Glen Ith’s Enduring Legacy

This week, in a 3-0 opinion, the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals ruled that the Forest Service’s use of a deer habitat suitability model was “arbitrary and capricious” because key numbers in the model were altered without any rational explanation. The case is a testament to the persistence of Greenpeace’s Larry Edwards, a Sitka resident, the advocacy skills of co-plaintiff Cascadia Wildlands Project (one of my favorite grassroots outfits for its combination of smarts and passion) and their legal counsel’s (Chris Winter of Crag Law Center) talents.

It is the back story that it is especially poignant to me.

That story begins six years ago, when Tongass wildlife biologist Glen Ith emailed me aerial photographs taken by an Alaska Department of Fish and Game employee. The photos showed on-going logging road construction to access the Overlook project area. Overlook was an old-growth forest timber sale that is prime winter range habitat for Sitka black tail deer. What caught Glen’s eye was that the Forest Service had not yet completed the Overlook NEPA analysis, but had already started building the roads. Turns out that there were several million dollars that Senator Ted Stevens (R-AK) had earmarked for Tongass road work; money that if not spent by fiscal year’s end would be lost to the Forest Service, and incur Stevens’ displeasure. Overlook’s NEPA documents were behind schedule, but that didn’t stop the road engineers from moving forward. [NB: The conspiracy to spend the money was broader than the engineers alone, including district and forest-level planning staff, line officers, and contracting officials.]

Glen and FSEEE filed suit, challenging the Overlook and Traitors Cove (another site of illegal “advance” work) road building. It was the first-ever environmental lawsuit by a Forest Service employee. We won. The Forest Service retaliated, suspended Glen from work, and eliminated his job. Several days thereafter, Glen passed away from sudden heart failure.

Early on in our roads litigation, Glen told me that the Tongass was using irrational numbers in its deer habitat capability model. He wanted to cure the errors. We agreed the on-going roads case wasn’t the place to do so, primarily because the issue was not ripe as the timber sale environmental reviews were not complete. Glen said he would try to work internally to fix the modeling problem, but he wasn’t confident he would be successful. He believed the errors were intentionally designed to allow the Forest Service to defend logging high-value old-growth forest habitat.

Glen assiduously documented the problems with the deer habitat model; documents that Greenpeace’s Larry Edwards later found in the administrative records. Glen also administratively appealed the Scott Peak sale on these grounds.

Larry Edwards dedicated this week’s court victory to Glen’s memory.

Out-of-Date Planning

Last week the Colville and Okanogan-Wenatchee National Forests released their “proposed actions,” a new step in NFMA planning preceding the draft EIS and proposed forest plan.

This gem from both plans (the plans appear identical — only the maps differ) illustrates that adding more process does not make plans any more timely:

While the U.S. demand for timber remains relatively high and is expected to increase in the future (USDA FS 2000), timber harvests from 1990 to 2002 in Washington have declined by 39 percent (Washington State Department of Natural Resources 2004). United States lumber markets have relied increasingly on foreign imports, such as from Canada, to help offset declining timber harvests in the state. Softwood lumber imports into the Seattle Customs District from 1992 to 2002 have increased by 11 percent (Warren 2004), while inflation adjusted wholesale prices for Douglas-fir 2x4s have dropped by 33 percent (Warren 2004).

Washington DNR has issued no fewer than five state-wide timber harvest reports since the 2004 report cited here. And Deb Warren has published five more annual statistical summaries, up through 2009, since the 2004 version.

Lo and behold, using the more up-to-date statistics shows that softwood lumber imports into the Seattle Customs District have dropped 70% since 2002 — a far different picture from the 11% increase claimed in the already out-of-date plan.

I suspect that these “proposed actions” were actually written several years ago and have been gathering dust on the shelves while the Forest Service tried to sort out its planning process. Rather than up-date these documents, the FS just slid them out the door with nary a glance.

Just one more illustration of how silly it is for the FS to bite off more planning than it can chew.

Ed Quillen on Maximum Trashing Utilization: Colorado Voices I

For those of you who don’t read the Denver Post or High Country News, you might not be familiar with the unique voice of Ed Quillen. I don’t always agree with the guy, but I find this curmudgeonly Salida resident to be a true Interior West voice and always worth a read. Here he is on a new concept for land use (this is related to the F.S. because of the coal mine, which is currently in (guess what?) litigation). In our next post we will hear another Colorado voice on coal mining in the same area. I think it’s interesting to contrast the perspectives.

Below is most of the op-ed; the rest can be found here.

The West could become a greener place with the help of a policy I call Maximum Trashing Utilization, or MTU. Its fundamental concept is simple: Get the maximum benefit from every disturbance of the environment. If that requires changes in regulations, or perhaps some economic adjustments, let’s just do it. The more benefit we get from “trashing,” the less trashing we’ll need to do.

Consider the vast networks of diversions, reservoirs, canals and ditches we have built to irrigate crops here in the Great American Desert. By and large, the water moves by gravity. And as everyone who has ever seen a water wheel knows, water in motion can be a source of useful energy, for anything from a gristmill to electrical generation.

With those irrigation works, we’ve already damaged the environment by removing water from its natural course. So why not get the maximum benefit by generating electricity at every irrigation reservoir and ditch drop?

There are some roadblocks, though. A state-granted right to divert water doesn’t necessarily include the legal right to run it through a turbine in the process. Hydro projects, no matter how small, must be licensed by the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission, and that can be a long and expensive process, not worth the trouble for the small low-head generating units that would work with irrigation systems.

Furthermore, the power generally needs to go somewhere beyond the irrigation system, which may require building new power lines — and those are often sources of contention and yet more reviews and hearings.

The upshot of all this is “regulatory uncertainty,” which leads to a reluctance to invest even as new technologies are developed for low-head (less than 16 feet of fall) hydro and in-stream generation that hardly affect stream flow.

Now, I realize that we need some regulation; environmental protection is important. But our regulatory system also ought to encourage getting the maximum possible benefit — i.e., relatively clean energy — from the damage that’s already being done. And if making it economically feasible requires subsidies in some instances, well, why not? It’s not as though other energy sources, from crude oil to solar, don’t get subsidies.

Another way to achieve Maximum Trashing Utilization is known as cogeneration. Basically, it means generating electricity with a thermal plant, and putting the waste heat to use.

One of my brothers designs and installs cogeneration units for commercial laundries. A stationary automotive engine is modified to run on natural gas instead of gasoline. It turns a generator to help power the laundry’s machinery. The hot exhaust from the engine replaces the burner on a conventional large water heater, whose intake water has been preheated in the process of cooling the engine.

The result is a lower overall energy bill for the laundry, and more use of the energy from the natural gas.

What’s not to like about it? Well, when my brother added onto his house and wanted to heat it with a small cogeneration unit, he hit all sorts of regulatory barriers, from the city building code and various zoning laws to the municipal utility company’s strenuous efforts not to buy any surplus power he generated. After two years of fighting, he gave up.

There has been some progress on the regulatory front. Back in 2008, High Country News carried a story about methane escaping from Western coal mines. Methane is a flammable gas (it and its close chemical relative ethane are the major components of natural gas) that is given off by coal as it decomposes underground.

Since methane is flammable and sometimes explosive, mine safety requires venting it away from the working area.

Logically, this methane should be burned in a productive way. Unburned methane is more than 20 times as potent a greenhouse gas as the carbon dioxide produced by combustion. Plus, there’s the energy from burning it, which could be used to heat homes or generate electricity.

But certain regulatory policies for coal mines on federal land prevented the methane from being put to public use. Essentially, the mining companies had the right to use the coal, but not the methane. For safety reasons, they have to vent it — but they couldn’t put it to work.

That’s changed recently, at least on a case-by-case basis. The Interior Department now allows the capture and sale of methane. But is it economical to do so when the methane is diffuse and the nearest pipeline might lie miles away?

“We’ve tried to look at it every way in the world. If it were economic to do, we would already be doing it. It would add to our income.” That’s what James Cooper, president of Oxbow Mining, which operates the Elk Creek Mine in western Colorado, told a Grand Junction business journal.

Cap-and-trade legislation might change the economics by paying the coal company to capture methane. It’s unlikely to be enacted in the current political climate, but again, if some subsidies are required to get MTU, there are certainly worse ways to spend public money.

Note from Sharon: It would be simpler, and more likely to succeed, in my opinion, to write surgical legislation that would treat the methane from underground coal mines (or at least ones on federal land) as a pollutant and require capture; Mark Squillace, Director of the Natural Resources Law Program at University of Colorado attempted to do this last year. A more productive way of making useful policy than litigating on the NEPA, without running up bills for government and NGO attorneys. In my opinion.