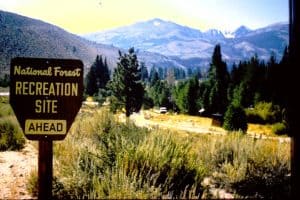

I soon fancied myself “the fastest staple gun in the West” for the way I kept fresh Smokey Bear posters displayed all over the district.

My greatest fire prevention ally as a Toiyabe National Forest fire prevention guard was Smokey Bear. That’s backward, of course. I was Smokey’s ally, and only one of many throughout the United States.

Smokey had been America’s “forest fire preventin’ bear” for nineteen years by the time I became the Bridgeport Ranger District fire prevention guard in 1963. With his famous “Only you can prevent forest fires!” tag line, Smokey had become the most recognized symbol in advertising history.

I was proud to be on Smokey’s team, and used the Cooperative Forest Fire Prevention Program materials I ordered each year to the fullest. I soon—albeit secretly—fancied myself “the fastest staple gun in the West” for the way I kept fresh Smokey Bear posters displayed on well-maintained peak-roofed signboards—all strategically located, by the way, in accordance with a fire prevention sign plan—all over the district.

In addition to stapling these colorful posters to these signboards, I installed and maintained the signboards—crafted in the ranger station’s shop by fire crew members on days they were not working in the field—all over the district. And so, in addition to its pumper unit and fire tools, my patrol rig was equipped with a post-hole digger, tamping bar, and other sign structure installation tools as well as a five-gallon bucket of brown stain and paint brushes to keep both newly installed as well as older signage looking sharp.

Smokey Bear posters were also displayed in Bridgeport’s public buildings, stores, restaurants, motels, and gas stations as well as at resorts and businesses throughout the district. A supply of Smokey Bear comic books for children met while on patrol was always in the patrol truck along with free national forest maps—yep, they were free in those days—and other information for public distribution. Every campfire permit issued on the district had a small Smokey Bear fire prevention reminder stapled to it.

All of these efforts were, of course, supplementary to the dozens of personal fire prevention contacts with forest visitors and users which I made every day while on patrol.

Although I could not back up my belief with statistics that all these fire prevention efforts actually prevented any wildfires, the district ranger and the fire control officer and I were convinced they did.

Adapted from the 2018 third edition of Toiyabe Patrol, the writer’s memoir of five U.S. Forest Service summers on the Toiyabe National Forest in the 1960s.