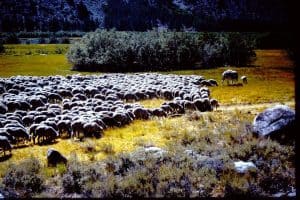

Sheep grazed on allotments on the Bridgeport Ranger District, Toiyabe National Forest.

As the eastern Sierra summer of 1966 wore on, the Toiyabe National Forest dried out. By the middle of July the fire danger was extreme, and fire safety restrictions including prohibition of open campfires outside developed campgrounds were announced. These required special signage and increased the intensity of my patrols.

I was on patrol in the Twin Lakes area early one August afternoon. It had been a relatively slow morning and, just as I began to wish the pace would pick up, it did. But not in any way I expected.

“D-4-5, this is KMB-652.” It was Pam, the district clerk.

“KMB-652, this is D-4-5, over.”

“Les, we’ve had a couple reports of a dead sheep in the Honeymoon Flats Campground. Will you check it out, please?”

A dead sheep? I hadn’t seen sheep in the Twin Lakes basin for days. This one, I surmised, must be a stray from an allotment. Oh well, all in a day’s work. Hoping the poor critter wouldn’t be too ripe, I responded affirmatively.

A few minutes later, I approached Honeymoon Flat. The sheep wasn’t difficult to locate. Lying just off the highway, on the road into the campground, it appeared to have drawn more people than flies since its demise. The small crowd’s attention shifted to me as I pulled up alongside the wooly carcass of a fully-grown ewe.

Howdy,” I said to no-one in particular, closing the patrol truck door behind me. A cool afternoon breeze blew off the Sierra and stirred the aspen.

“It’s a dead sheep!” explained a helpful bystander. I nodded agreement and smiled thanks for his assessment. “Are you going to get rid of it?”

“Yes, sir.” Scratching my head briefly, I sized up the problem and then, in reluctant resignation, strode purposefully toward part of the solution. The crowd’s eyes followed me intently.

Fortunately, the campground garbage had been collected recently, and I found an almost empty can. Quickly transferring its content into another, I hauled the can back and pushed it under the ewe. Because dead animals don’t exactly leap into garbage cans, I had to pry this one into its casket with a shovel. Once the corpse was in the can, I set it upright and slapped on the lid. Then, dropping the tailgate to the horizontal position, I dragged the canned sheep to the rear of the patrol truck. There was just enough room for the can to ride behind the pumper unit and the fire tool box.

But one problem remained. That was one heavy garbage can! I doubt I could have lifted it, at least not gracefully. But an independent streak doesn’t allow me to ask for help—even in situations like that. With all eyes on me, I stooped to pick it up….

“Here, let me give you a hand,” volunteered a burly fellow. Saved!

“Thanks.”

We easily lifted the can onto the tailgate, where I lashed it securely in place. Having a dead sheep fall off one’s patrol truck onto the highway, it seemed to me, would be most embarrassing. With a ripple of applause and a few chuckles, the crowd dispersed. And the sheep was soon disposed of in the nearby Forest Service dump I would burn in a few days.

Adapted from the 2018 third edition of Toiyabe Patrol, the writer’s memoir of five U.S. Forest Service summers on the Toiyabe National Forest in the 1960s.

Ten years as a sheep rancher taught me that sheep have an infinite capacity for dropping dead and zero inclination to avoid doing so. My John Deere tractor’s front bucket was perfect for carcass disposal in the woodlot. By next spring only bones and some fleece would survive the coyotes.