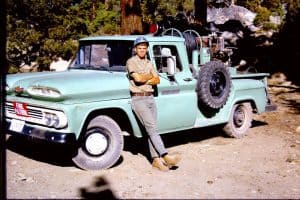

Les Joslin and Fire Patrol Rig

Burning off Forest Service dumps, to which campground and permittee refuse was hauled, was a hazard reduction part of my 1960s Toiyabe National Forest fire prevention guard job and just about the only part of the job I really didn’t enjoy.

Why not? Well, it started cold and dark, got dirty and smelly, and finished hot and dry. It involved getting up long before sunup, loading a couple five-gallon cans of diesel fuel onto the patrol truck, driving to the dump to be burned that morning, pushing garbage and trash piled up around the sides into the pit, anointing the whole mess with diesel fuel, touching it off with a fusee, watching the surrounding area for spot fires while the dump burned, and making sure the whole thing was dead out by about ten o’clock before the winds came up.

Oh, dump burning had its compensations, like communing with Mono Lake’s seagulls which winged north to forage for tidbit supplements to their brine shrimp diets. Once, at the Virginia Lakes dump, I saw a bear. And once, burning the Twin Lakes dump led to an amusing encounter with some fishermen.

Extinguishing the dump fire had drained the patrol truck’s pumper tank, so I drove to the nearby Timber Harvest Road bridge over Robinson Creek for a refill. Crossing the bridge, I pulled off the road and backed down to the creek. Not long after I had dropped the drafting hose into the stream and reversed the pump, two vehicles halted on the bridge. One was a flashy convertible and the other a battered Jeep. The occupants gestured in my direction, pulled off the road, and parked next to the patrol truck.

At first I thought something might be up. Perhaps they were going to report a fire! But the rapid unloading of fishing gear soon betrayed their misguided urgency. This had happened before.

“Hey! Are they biggies?” a couple blurted in unison as they scrambled past me to peer into the stream where my drafting hose lay. The rest of the pack followed, clutching fishing rods and carrying tackle boxes.

Feigning ignorance, I responded to their question with another. “Big whats?”

“Rainbows! Man, you know! Trout! Fish! You are the fish man, aren’t you?”

“No, I’m sorry. I’m not the fish man,” I answered almost apologetically. “Fish are planted by the California Department of Fish and Game. I work for the U.S. Forest Service.” Then, after a pause, I added with a smile and only slightly exaggerated pride, “This is a fire truck.”

“A fire truck?” They looked unimpressed, to say the least. More like disdainful. But the awful truth was beginning to sink in. “You mean…you’re not the fish man?”

“Sorry,” I shrugged. They probably had been looking for a “fish man” with a “fish truck” all morning. “I’m just filling the tank on this fire truck.” I slapped the hose reel affectionately. Then I informed them of the days on which the Department of Fish and Game usually planted fish in Robinson Creek. Needless to say, those fishermen—a dismayed “that’s a fire truck” look on their faces—didn’t hang around very long.

Adapted from the 2018 third edition of Toiyabe Patrol, the writer’s memoir of five U.S. Forest Service summers on the Toiyabe National Forest in the 1960s.