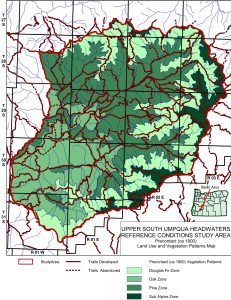

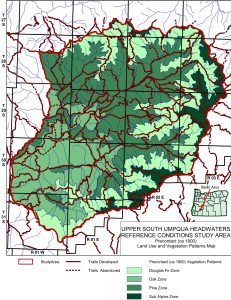

The following map and photos are from a research project I completed a little more than 10 years ago. Management of old-growth trees for their preservation begins with their definition and location. Competition and crown fires are among the greatest apparent threats: http://www.orww.org/Osbornes_Project/Rivers/Umpqua/South/Upper_Headwaters_Project/ca_1800_Forest_Zones/

The 2010 “Upper South Umpqua Headwaters Precontact Reference Conditions Study” was authorized by the Douglas County Board of Commissioners, in cooperation with the USDA Umpqua National Forest and the Cow Creek Band of Umpqua Tribe of Indians. Research focus was to determine approximate forest conditions for the study area during the 1800 to 1825 time period. Primary sources of information included General Land Office original land survey notes and maps from 1857 to 1938, historical photos from 1899 to 1944, historical maps from 1900 to 1970, Osborne fire lookout panoramas from 1932 to 1938, aerial photos from 1939 to 1945, and nearly 3000 comprehensive documentary photographs in 2010. From these sources a series of GIS maps were constructed by the Douglas County Surveyors Office and developed into likely vegetation and trail maps for the ca. 1800 to 1825 time period.

Through this process it was determined that four basic types, or “zones,” of vegetation existed prior to white contact and decimation of local communities by introduced diseases. These four types can be delineated by elevation and corroborated by the existence of old-growth trees and other persistent vegetation patterns in excess of 200 years of age. In each of the following photographs, research assistant Nana Lapham serves as a human scale to an old-growth representative of an earlier forest condition. The Oak Zone photo features a lower elevation 200+ year old black oak in a former oak and pine savannah; the Pine Zone photo shows an old-growth sugar pine, likewise in a former savannah, at a higher elevation; the Douglas Fir Zone photo shows the transition from lower elevation pine to higher elevation Douglas fir, and indicates the much lower density of trees 200 years ago; and the Subalpine Zone photo shows old-growth cedar and young true fir saplings in the highest areas of the study area.

Oak Zone This photo shows old-growth relict pine and oak with invasive Douglas fir on Pickett Butte in 2010. Relatively young white oak, black oak, and pine savannahs, extensive grassland meadows and prairies, and patches of similarly much younger Douglas fir, redcedar, and pine typified much of the western and lower elevation (below 2,400 feet) portions of the study area 200 years ago. The presence and arrangements of these plants, as well as widespread populations of camas, cat’s ears, fawn lilies, iris, tarweed, yampah, and hazel, indicate regular systematic use of the landscape by people – most likely mostly Takelman-speakers — at that time. The average number of trees larger than saplings per acre was probably ten or less. Human occupation of this zone was likely year-round, with relatively large seasonal villages and campgrounds near the mouth of Jackson Creek and at South Umpqua Falls: two locations that (according to historical reports) were heavily used during times of anadromous salmonid and lamprey eel runs.

Pine Zone This photo shows an old-growth sugar pine, with invasive Douglas fir, pine, and madrone, in a former savannah near Squaw Flat in 2010. The presence of ponderosa pine and sugar pine, with few understory or directly competitive trees, typified much of the mid-slope (2,400 to 3,800 foot elevation) forest in the study area 200 years ago. The pine zone was typically open and park-like with large — though much younger than present — widely spaced pines; patches of oak, chinquapin, serviceberry, and hazel; scattered stands of Douglas fir; and grassy meadows and berry patches. The average number of 8-inch diameter and larger trees per acre was likely less than 20. The location and age of remnant old-growth trees indicate regular seasonal use of the pine forestlands by Takelmans from lower elevations and southern Molalla from higher elevations. The harvesting of ponderosa pine cambium in the spring and sugar pine, hazel, and chinquapin nuts in the fall may have been times of most intensive occupation of this zone. Hunting for game animals with dogs by Molallans likely occurred on a year-round basis, depending on the daily and seasonal movements of deer, bear, and elk.

Douglas Fir Zone This photo shows an old-growth ponderosa pine and an old-growth Douglas fir, with invasive pine and Douglas fir, on the cusp between the Pine Zone and the Douglas Fir Zone above French Creek, in the Black Rock Fork subbasin in 2010. Although Douglas fir of a wide range of ages was present in almost every type of environment in the study area 200 years ago, it existed in nearly pure stands from 3,800 to 5,000 feet elevation, separating the lower elevation pine stands from the higher elevation subalpine vegetation types. Due to generally steep slopes, isolated location, seasonal snow, and relative lack of food plants, accessible water, and animals, this zone likely experienced the least amount of daily or seasonal use and occupation by people. Although the densest stands of trees in the study area occurred in this zone, they were still often open and park-like with only 20 to 30 trees per acre 200 years ago. Grassy meadows and fern brakes also existed throughout this zone, indicating likely human use and maintenance on a fairly regular basis. Established seasonal ridgeline and streamside trails were used by both game animals and people to reach lower and upper elevations, where food and freshwater were more available. Ridgeline trail networks that crisscrossed this zone were regularly burned to promote grassy meadows, bracken fern, beargrass, serviceberry and other useful food and fiber plants.

Subalpine Zone This photo shows old-growth cedar and an historical cabin at Mud Lake on the perimeter of French Junction prairie in 2010. The highest elevations of the study area (above 5,000 feet) formed an international network of foot trails in precontact time that connected Tribes of the South Umpqua with Indian nations in Rogue River, Klamath Falls, Deschutes River, Willamette Valley, Columbia River, and beyond. This seasonal “travel zone” was covered in snow much of the year, but contained extensive fields of shrubs, forbs, and grasses: huckleberries, manzanita, camas, beargrass, and other berries, fruits, nuts, bulbs, edible roots, fuels, and fibers that were readily available in the summer and early fall. The existence of numerous year-round springs, likely “vision quest” sites, flats, benches, and gently sloping ridgelines add further evidence of intensive year-round and seasonal use; more particularly by southern Molallan hunters, who used dogs and snowshoes to hunt elk and other prized game animals throughout the study area and had ready access to the extensive fields of huckleberries and international trade routes. Other Tribes undoubtedly visited these lands to hunt, harvest or trade for elk hides, huckleberries, and beargrass, and to move trade goods along the landscape. Latgawans and other Takelman speakers from lower elevations likely gathered at Huckleberry Lake, Quartz Mountain, and Pup Prairie areas as well. Klamaths likely moved slaves and other trade goods along the eastern ridgelines, following the Klamath Trail to campgrounds in the Black Rock and French Junction areas, before heading north along Camas Creek into the North Umpqua Basin, or south into the Rogue River basin. It is also possible that Paiutes from the east, southern Molallans from the north, and Kalapuyan-speaking Yoncallans from the northwest also entered this area at these times; also possibly for reasons of hunting, trade, harvesting of favored crops, spirit quests, or simply visiting friends and relatives. Much of this area could be characterized by the ridgeline trails and extensive fields of prized huckleberries, which also contained scattered trees: principally redcedar, Douglas fir, and Shasta red fir.