By Alex Renirie

In this historic year –the first legislative session after the International Panel on Climate Change warned in a special report in late 2018 that we have less than 12 years to make “rapid and far-reaching transitions in land, energy, industry, buildings, transport, and cities,” with human-caused CO2 emissions dropping “by about 45 percent from 2010 levels by 2030, reaching ‘net zero’ around 2050”– environmental groups in Oregon are up against more challenging odds than ever.

Just weeks into the session, The Oregonian issued a report calling out the state’s political system for its increasingly corrupt campaign finance laws. The four-part series revealed that Oregon’s environmental regulations have been getting weaker for decades while the state has been working its way toward number one in the country for highest corporate campaign contributions per capita. Nowhere is the payoff more obvious than in the strong political ties between the timber industry and state legislators—Oregon is number one for campaign contributions from the timber industry nationally. As a result of this influence, the timber industry remains virtually unregulated in the state, with weaker forest practices standards than any of its neighboring states. And it continues to escape responsibility for its climate impacts. As Center for Sustainable Economy has documented and Oregon State University researchers have confirmed, the timber industry is the number one source of greenhouse gas emissions in the state—yet these emissions are completely uncounted and not covered by existing proposed climate legislation.

Thus, it was no surprise that there was pushback when the Oregon Safe Waters Act, sponsored by State Representatives Andrea Salinas (D-HD38) and Karin Power (D-HD41)and the Oregon Forest Carbon Incentives Act, sponsored by State Representatives Andrea Salinas (D-HD38) and Rob Nosse (D-HD42) and State Senator Kathleen Taylor (D-SD21) were formally introduced. Combined, both bills were endorsed by the Sustainable Energy & Economy Network (SEEN), Pacific Rivers, and 50 other partner organizations across the state. Both bills would restrict the environmental, economic and human health impacts of the timber industry and attempt to remedy a serious flaw in existing Oregon law namely: in the face of a changing climate, Oregon should amend its forestry laws to protect vulnerable drinking water sources, incentivize sustainable forestry rather than massive clearcuts, and turn our forests back into carbon sinks, not carbon sources.

The Oregon Forest Carbon Incentives Act, HB 2659, as explained on the SEEN site would mean, “if you’re an Oregon forestland owner, you should not be receiving tax breaks for land that is covered by clearcuts, logging roads, and timber plantations. Taxpayer support should be reserved for owners who maintain healthy forests on their lands and use good practices.” HB 2659 would make receipt of various tax breaks contingent upon the land being covered in actual forests, not dense plantations that are biological deserts, in order to support landowners who choose more sustainable methods to log and leave a climate resilient forest behind.

The Oregon Safe Waters Act (HB 2656) prohibits most chemical spraying and clearcuts in Oregon’s drinking watersheds. On March 12, 2019, the House Committee on Energy and Environment heard HB2656, the Oregon Safe Waters Act. Between supporters and opponents, attendees packed three entire hearing rooms. Over 100 people signed up to give public comment.

From big partners like the Sierra Club’s Oregon chapter and Oregon Wild to smaller community advocacy groups like the dedicated folks at Rockaway Beach Citizens for Watershed Protection, to the Williams Creek Watershed Council and Clatsop Soil & Water Conservation District, we were encouraged to see that Oregonians from all over the state were eager to pass this legislation.

Our panel of experts in support of the HB2656 included SEEN’s Dr. John Talberth, Greg Haller of Pacific Rivers, and Tina Schweickert, former water resources coordinator for the city of Salem. Haller focused on the critical message that the bill was not designed to affect small landowners, despite timber industry claims: The real target of the bill is Wall Street-funded timber companies that don’t care about the community impacts. Talberth focused his testimony on the depletion of water resources in industrially logged areas and the increased risks of fire and toxic algae blooms that unsustainable forestry practices cause. Schweikert highlighted the contamination of Salem’s drinking water by a toxic algae bloom in 2018 and strongly encouraged the committee to take proactive measures to safeguard the entire state’s water supplies.

Oregon Department of Forestry Director Peter Dougherty also testified, largely repeating claims made by industry that water quality in Oregon is safe across the board. He presented research from the Oregon Department of Environmental Quality showing that water quality in forestland is the best of any land use type, but upon questioning by Representative Salinas, admitted that not all watersheds were monitored and that he didn’t know how many were represented in the referenced study.

After over an hour of introductions and expert testimony, Committee Chair Ken Helm began a dramatically shortened public comment period, prioritizing those who had traveled the farthest to attend the hearing, while extending the deadline for others to submit comments in writing by several days. Only twelve people of over a hundred that signed up had the chance to give their testimony. Still, we heard from some powerful speakers – citizens of Rockaway Beach demonstrated how clearcutting has decimated their watersheds on the coast, and a small timber owner reminded us that utilizing climate- and water-smart forestry practices is not only possible, but profitable. In opposing comments, we heard nearly identical claims that Oregon’s drinking water is perfectly safe and that the bill would put people out of work. Our opponents seemed largely unaware or uninterested in the proposal’s central intent to proactively protect watersheds from increasing drought, fire, and algal toxicity in the face of a warming climate.

The combination of an extremely shortened public comment session, the one-dimensional arguments from those opposing the bill, and several committee members clearly more interested in asking questions of industry representatives than bill sponsors, made it a frustrating experience overall. Instead of moving the bill to a work group so that concerns could be addressed head on, the committee seemed perfectly willing to submit to the industry’s scare tactics and let the bill die.

At the Forest Carbon Initiatives Act hearing on March 26th, we again were faced with poor scheduling and limited opportunity for public comment. At the last minute, the House Natural Resource Committee switched the hearing date to 8 a.m, two days earlier than previously scheduled. With other bills to address in a tight timeframe, we were once again left with insufficient time even for expert testimony and very limited time for the public to weigh in.

Nevertheless, again, our panel of experts supporting the bill was excellent and emphasized that the timber industry is given extremely favorable treatment in the form of tax breaks and subsidies from our state government. In return for these tax breaks (doled out by Oregon taxpayers), we are left with damaged land at higher risk for flooding, contamination, biodiversity loss, and more rapid climate change. In his slideshow, Talberth presented two photos to demonstrate the point – one of a large clearcut, and one of a healthy forest – and implored legislators to change their minds about which of those forest landowners deserves a tax incentive. If we are serious about tackling climate change and increasing forest carbon sequestration, we should be offering benefits to those who leave healthy forests behind. And doing so would bring in hundreds of millions of dollars in tax revenue for schools, infrastructure, and services to rural counties.

Oregon Department of Forestry Director’s Dougherty again offered predictable testimony opposing the bill, this time explaining that Oregon’s existing forest land tax structures are entirely reasonable and based on a long history of collaboration between loggers and the state government (no surprise there). Though it may be acceptable business-as-usual for those benefitting from the current system, there is no denying that current tax laws artificially boost timber harvests in Oregon to levels far beyond what we would see under a free market.

Unfortunately, neither bill was advanced to a work session this year, but we are optimistic about the partnerships we built and hopeful that a renewed campaign for the Forest Carbon Incentives Act will gain traction in the 2020 revenue-focused legislature. We are so grateful to the dozens of our partners and supporters who traveled from around the state to attend one or both hearings. And we thank the hundreds more that filed comments online. With so much support, we surely communicated to lawmakers that these issues aren’t going anywhere and that we will be back.

The bills’ co-sponsors deserve our biggest gratitude – Representative Andrea Salinas (D-HD38) championed both bills and made clear that while the problems we face are grave, the solutions are attainable. She offered several times throughout both hearings to sit down with the opposition and discuss how to address these challenges together. Representative Karin Power (D-HD41), co-sponsor of the Oregon Safe Waters Act, eloquently portrayed that bill as an equity issue. She advocated for the rights of rural communities, stating that those who don’t have the resources to buy their watersheds should not be left to bear the cost of upstream industrial polluters. We also appreciate the support of Senator Kathleen Taylor (D-SD21) and Representative Rob Nosse (D-HD42), co-sponsors of the Forest Carbon Initiatives Act.

While some of our opposition suggested that the bills were simply reminiscent of the timber wars of the 1980s, it should be clear to anyone who is paying attention that the environmental problems we face today couldn’t be more distinct from those of the ‘80s. Climate change is upon us. It is more glaringly apparent in every fire season, every algal bloom in a drinking watershed left sitting under hotter summer suns, and every threatened species left with less available habitat. Our ecosystems are more vulnerable than ever, and common-sense updates to Oregon’s forestry laws should be a quick and easy step towards making Oregon the world-class carbon sink it was designed to be.

Despite some setbacks this year, we will continue pushing to reform the timber industry through the Sustainable Energy and Economy Network, and with our allies. We know our coalitions will only grow stronger and our arguments more urgent. These problems can and must be solved and, with your support, they will be.

Alex Renirie is a Forest Policy Advocate at Center for Sustainable Economy, and Legislative Liaison with the Sustainable Energy and Economy Network.

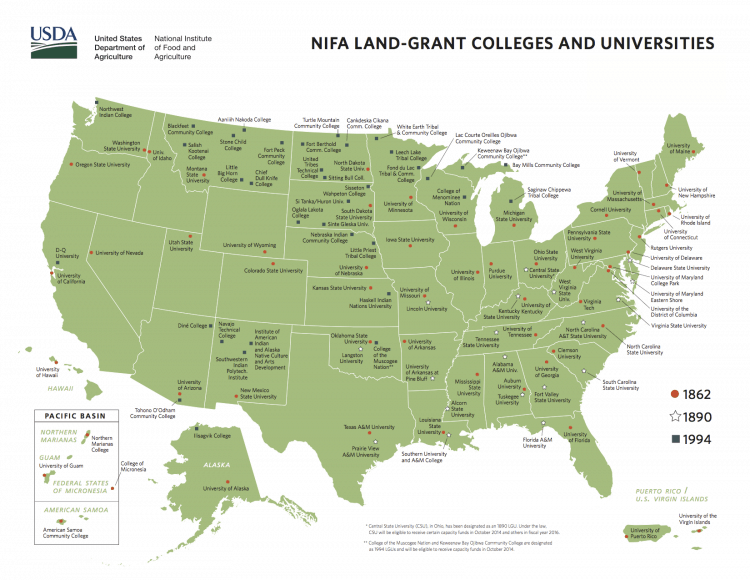

I ran across this NPR story about possibly moving USDA Agencies NIFA and ERS out of the Washington D.C. area. I think it’s altogether possible to critique initiatives without hyperbole e.g. “hostility toward science” but the more intense the expression, the more likely to be quoted, I guess.

I ran across this NPR story about possibly moving USDA Agencies NIFA and ERS out of the Washington D.C. area. I think it’s altogether possible to critique initiatives without hyperbole e.g. “hostility toward science” but the more intense the expression, the more likely to be quoted, I guess.