The following press release was sent out yesterday by Portland State University. – mk

Researchers at Portland State University and Oregon State University looking at the aftermath of wildfires in southwestern Oregon and northern California found that after 20 years, even in severely burned areas, Douglas-fir grew back on its own without the need for salvage logging and replanting.

The study, published online Oct. 26 in the journal Forest Ecology and Management, is the latest to address the contentious issue of whether forest managers should log dead timber and plant new trees after fires, or let them regenerate on their own.

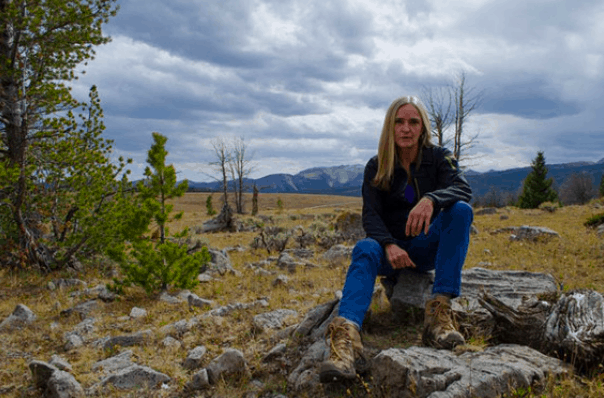

Melissa Lucash, an assistant research professor of geography in PSU’s College of Liberal Arts and Sciences and a co-author of the study, said that concerns in the Klamath over whether conifer forests would regenerate after high-severity fires have led to salvage logging, replanting and shrub removal on federal lands throughout the region.

But the study found that the density of Douglas-fir was relatively high after 20 years and was unaffected by whether or not a site had been managed.

“This is an area where forest managers are really worried that the Douglas-fir won’t come back, but what we found is that they come back just fine on their own,” she said. “We forget the power of natural regeneration and that these burned sites don’t need to be salvage logged and planted.”

Lucash suggests that those resources could instead be reallocated elsewhere, perhaps to thinning forests to prevent high-severity wildfires.

The research team also included Maria Jose Lopez, a research associate at Universidad del Cono Sur de las Americas in Paraguay; Terry Marcey, a recent graduate of PSU’s Environmental Science and Management program; David Hibbs, a professor emeritus in Oregon State University’s College of Forestry; Jeff Shatford, a terrestrial habitat specialist in British Columbia’s Ministry of Forests, Lands, Natural Resource Operations and Rural Development; and Jonathan Thompson, a senior ecologist for Harvard Forest.

The authors sampled 62 field sites that had severely burned 20 years prior on both north and south slopes of the Klamath-Siskiyou Mountain — some of which had been salvaged logged and replanted and others that had been left to regenerate on its own.

Among the study’s findings:

• Aspect, or the direction a slope faces, played an important role in determining the effectiveness of post-fire practices.

• Density of Douglas-fir was higher on north than south aspects, but was unaffected by whether or not a site had been managed, suggesting that Douglas-fir regeneration is inherently less abundant on hot and dry sites and management does not influence the outcome.

• On the flip side, management practices increased the density of ponderosa pine on south aspects, but had no impact on north aspects. That finding suggests that with rising temperatures and increasing severity of fires in the region, management would be most effective when tailored to promote drought-tolerant ponderosa pine on south aspects.

• Managed sites had taller conifers, which can improve fire resistance, but also had fewer snags — an important habitat feature for bird, small mammals and amphibian species in the region.

The authors recommend that forest managers should avoid applying the same post-fire management practices everywhere and should instead tailor practices to specific objectives and the landscape context.