Bernhardt’s order to “stand down” came in a phone call to Gopaul Noojibail, acting Grand Teton Park superintendent late Friday. The call was made after Governor Gordon shared with Bernhardt a strongly-worded letter sent to Noojibail Friday afternoon. In the letter the Governor criticized the Park Service’s choice to “act unilaterally aerially executing mountain goats over the State of Wyoming’s objections.”

Perhaps there must be an interesting backstory there.

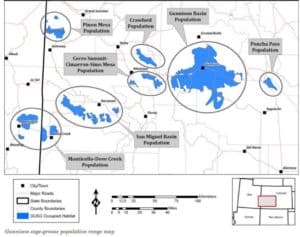

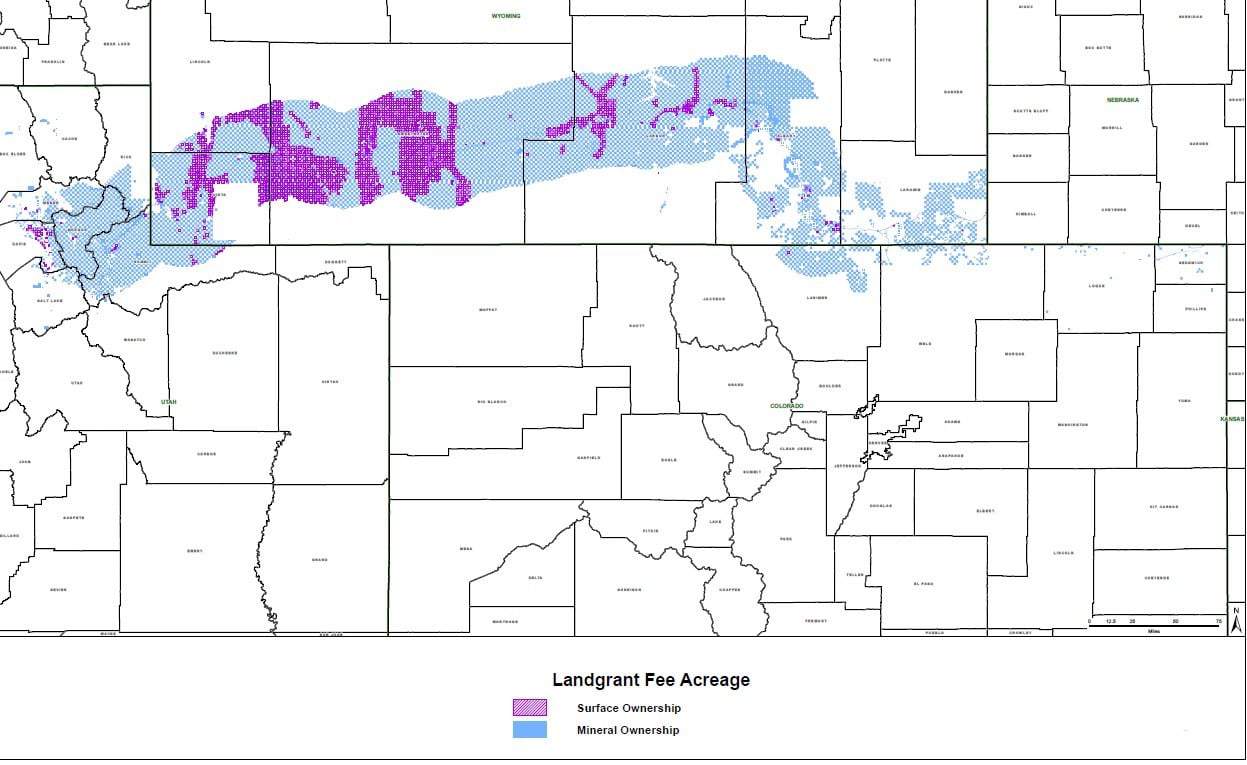

In other Wyoming news, state legislators are looking at buying a million acres (yes, a million!) of land.

Here’s a link to a story about it, and a statement by the Governor here (excerpts below) in the Cowboy State Daily:

Wyoming is not looking at this purchase to try to become a developer or a mining company; rather, we see the land grant opportunity as a way for the state to expand the areas where we already have expertise: land and mineral management.

This opportunity is not just about the money. This acquisition has enormous potential benefits for multiple-use that are valuable to all citizens of Wyoming, giving us the opportunity to assemble one of the largest contiguous pieces of public land in the continental United States. One that will benefit wildlife, hunters, fishermen and outdoor recreationists while achieving responsible development of rich natural resources.

Opportunities like this don’t come along very often. The land grant has only changed hands twice in its 150-plus year history. It’s likely that this would be the largest government purchase of private land since the United States purchased Alaska. That’s a big deal.

In this interesting article by Cat Urbiquit (who doesn’t seem to be a fan of the purchase), she talks specifically about how public public lands are in terms of recreation. Apparently Wyoming State Lands may be more restricted in terms of recreation than multiple-use federal lands such as BLM and FS. I think what is also interesting is the difference in terminology between “public” lands “owned by a government entity of some kind” versus “open to the public for various uses or not.” In many discussions people use the word to mean different things, which could contribute to the phenomenon of talking past each other.

State trust lands are to be managed to produce revenue, so they aren’t comparable to federal “public” lands like that of the Bureau of Land Management that are to be managed under a multiple-use mandate. But the State Land Board has adopted rules allowing the “public the privilege of hunting, fishing, and general recreational use on state trust lands.”

Recreational privileges on state trust lands come with sideboards: the lands must be legally accessible, and off-road use, overnight camping, open fires, and anything else that would damage the property are prohibited on state trust lands.

So you can hike, fish, and play on state trust lands by day, but no camping, fire pits, or charcoal grills (except in camping areas established by State Land Board). Cultivated croplands on state trust lands are not open to public use.

The state may issue permits for furbearer trapping and outfitting/guiding on state trust lands, (either exclusive or nonexclusive), and outfitters may be allowed to establish camp sites on exclusive permits.

Some state trust parcels are closed to all public use, while others have seasonal restrictions on public use, or restrictions on the discharge of firearms, hunting, or the use of motorized vehicles.