Highlights: increased capacity (hires), planting and seed orchard establishment, one-year anniversary of regional budget organization and drones for prescribed burning. Here’s a link.

Highlights: increased capacity (hires), planting and seed orchard establishment, one-year anniversary of regional budget organization and drones for prescribed burning. Here’s a link.

Other Regions, if you send I will post.

Community Sourced, Shared and Supported

Highlights: increased capacity (hires), planting and seed orchard establishment, one-year anniversary of regional budget organization and drones for prescribed burning. Here’s a link.

Highlights: increased capacity (hires), planting and seed orchard establishment, one-year anniversary of regional budget organization and drones for prescribed burning. Here’s a link.

Other Regions, if you send I will post.

Chelan County is moving ahead with plans for a wood products campus, which would use timber thinned from the county’s forest land to make a variety of wood products.

County commissioners and staff recently toured sawmills and biomass plants in the region to gather ideas for the future facility.

Chelan County Natural Resources Director Mike Kaputa says they’ll look to develop a hybrid type of plant, based on what they saw.

“I wouldn’t say that we saw any one facility that we thought was perfect for Chelan County, but some combination of those things we think is going to be perfect for Chelan County,” said Kaputa. “So, we have a lot of ideas, and we have a lot of partners that are working with us on this, so we’re going to be looking into this very seriously over the next few months.”

Among the stops the commissioners and staff made were in Colville and Wallowa, Ore.

In Colville, they toured Vaagan Brothers Lumber, a company started in the 1950s and today is a leader in the west in sustainable forestry.

In Wallowa, they toured the Heartwood Biomass facility. Heartwood takes wood that is underutilized by the traditional logging industry and turns it into various wood-based products.

Kaputa says they’ll be working to figure out what products can be derived from the Chelan County forest and what type of facility needs to be built.

“We’re going to be talking about, given the work that’s going to occur on the national forest here over the next five to 10 years, what are the best product lines that we think could come from that, and then what kind of infrastructure do we think we could bring here to support that,” Kaputa said.

He said the county has spent two years coming up with several assessments of the wood supply and the different product lines that could come from that wood supply in the forests of Chelan County.

Kaputa said some type of facility will be in place to serve as a wood products campus in two years. He said the price tag would be between $15-$20 million to build the facility and/or convert existing buildings into one of more plants.

He said funding could come through several sources, including county economic development sales tax collections as well as state partners and the forest service itself.

The county has a good neighbor authority agreement to with the forest service to go into the Okanogan Wenatchee National Forest and conduct the work to thin the forest.

The process of thinning the forest of excess timber and using the wood to produce useful products – lumber for building purposes, firewood, poles, wood chips, etc. – would help achieve the goal making the forest healthier and protecting it from wildfires.

Kaputa said the forest land in Chelan County needs held because the decline of the forest in the county is well documented and the need for treatment is well known and well documented.

“Chelan County is the highest risk community in the state for potential wildfire damage,” said Kaputa.

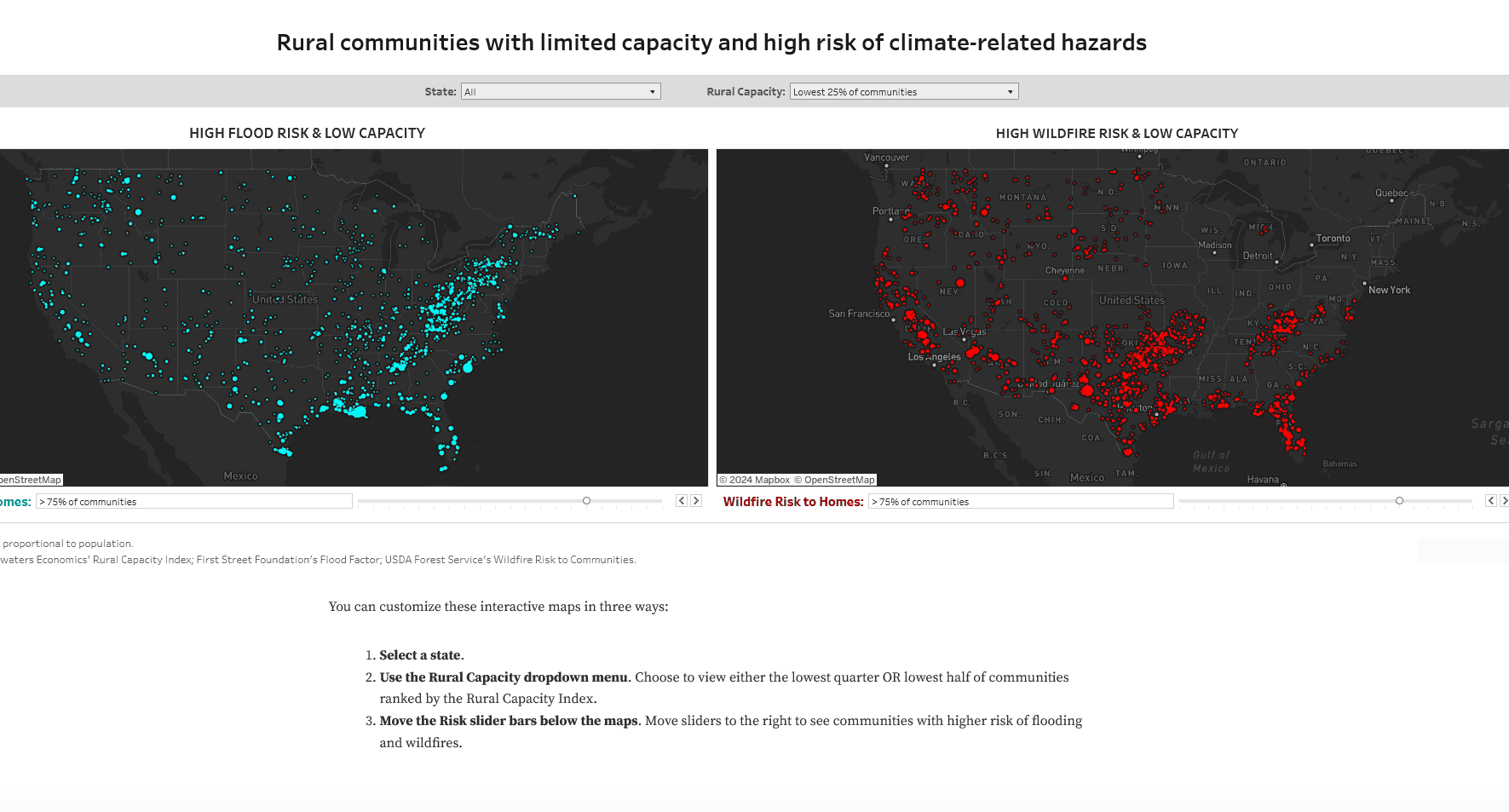

You can click on the above photo once and get a much better view. The big red blob on the Nevada wildfire map is Spring Creek Nevada.

You can click on the above photo once and get a much better view. The big red blob on the Nevada wildfire map is Spring Creek Nevada.

| Rural Capacity: | 50 out of 100 |

| 13th percentile in the U.S. |

| Wildfire Risk to Homes: | 100th percentile in the U.S. |

So I wondered what the landscape looked like for an area with the 100th percentile for wildfire risk.

This is not a critique of Headwaters, as they used the Forest Service’s (and not First Street’s) Wildfire Risk to Communities map.

I think groups who develop maps think that they will be useful. But I don’t know. It seems like these maps don’t always directly address the problem at hand, in this case, “does a community have hired or volunteer folks available and knowledgeable to apply for federal grants?”. I know some communities who don’t.. even though conceivably the area is generally fairly well off. Maybe another solution would be to make the federal granting procedures easier to understand. I have friends with high capacity who find the processes of applying for grants for wildfire mitigation in their communities to be more difficult and confusing than needs be.. plus State requirements for fed bucks transferred to the State. It would be interesting for the Forest Service or someone else to commission listening sessions for communities on their tribulations in acquiring funding, coordinating different programs’ requirements, and so on. Maybe someone has.

Anyway here’s the link.

The sliders (the default is 50%) for the flood and wildfire maps are really important. Here is Moab, Utah, which we might think is fairly well-disposed in terms of economics.

| Rural Capacity: | 53 out of 100 |

| 21st percentile in the U.S. |

| Wildfire Risk to Homes: | 62nd percentile in the U.S. |

If you go up to 80% of communities, you can find a place like Pagosa Springs

| Rural Capacity: | 49 out of 100 |

| 12th percentile in the U.S. |

| Wildfire Risk to Homes: | 85th percentile in the U.S. |

Or a community in my own area, Ellicott, CO

| Rural Capacity: | 53 out of 100 |

| 20th percentile in the U.S. |

| Wildfire Risk to Homes: | 85th percentile in the U.S. |

Now Ellicott is, for all practical purposes, a bedroom community for Colorado Springs in El Paso County, which is fairly well off. And county folks would be staffed to help communities apply for grants. But are they? Isn’t that the real question? Then there’s the question of what folks in Ellicott would actually do with the grant money, since it’s a grassland. Plan evacuations? Is Ellicott-only the right scale for that?

Communities need capacity—the staffing, resources, and expertise—to apply for funding, fulfill complex reporting requirements, and design, build, and maintain infrastructure projects over the long term. Many communities simply lack the staff—and the tax base to support staff—needed to apply for federal programs. Communities that put together applications are often outcompeted by higher-capacity, coastal cities. The places that lack capacity are often the places that most need infrastructure investments: places with a legacy of disinvestment including rural communities and communities of color.

Places that receive the most external funding – whether from state and federal programs or philanthropy – often have larger staff, more expertise, and deeper political influence, not necessarily greater merit. Communities that need the most assistance may be the least likely to even submit applications. For the United States to fully adapt to climate-driven threats and bolster aging infrastructure, its programs and policies must account for community capacity.

Where is capacity limited?

To help identify communities with limited capacity, Headwaters Economics created a new Rural Capacity Index. The Index is based on 12 variables that can function as proxies for community capacity. The variables incorporate metrics related to four categories of capacity: local government staff and expertise, institutional capacity, economic opportunity, and education and engagement. (Read more under Data Sources and Methods below.)

Results are available for counties, county subdivisions, communities, and tribal areas in the interactive map below. The tool displays data across the urban-to-rural continuum to illustrate the variability in community capacity across the country. The inclusion of metropolitan communities is necessary to show the comparatively lower capacity that exists in most rural communities.

Why not- call places that low on the economic scale and ask them what their barriers to applying for federal grants are? For some, being in the 100 years flood plain may not be a concern.

Anyway, their conclusions seem fairly straightforward.

Supporting communities

To achieve the infrastructure and climate adaptation goals in federal programs, funding agencies must consider community capacity. Programs may need to be structured differently and new strategies may need to be created to support under-served and historically disinvested communities.

Using the Index, community capacity can be supported in many ways:

- Provide direct funding. For communities with low Index scores, eliminate the need for competitive grants, which many lower-capacity communities lack the resources and expertise to apply for and administer. Federal and state programs can identify where the needs are greatest and allocate funding accordingly.

- Improve access to competitive grants.

- Allow funding to be used to build capacity—not just used for projects. For example, funding could be used for new staff positions and technical training to support long-term investments.

- Eliminate or reduce match requirements. City and county budgets in low-capacity communities may not have the revenue to meet matching requirements.

- Revise requirements for benefit-cost analyses. These technical reports are expensive and highly technical. They often undervalue the benefits of projects in lower-capacity and lower-income communities.

- Fund technical assistance. Administered by state or federal agencies or by nonprofit partners, technical assistance programs provide expertise in project identification, design, and implementation, as well as assistance in compiling grant proposals.

- Increase funding for multi-jurisdictional projects. Funding regional projects that leverage urban-rural partnerships can benefit low-capacity communities. This may require investment in regional institutions and organizations that can help coordinate resources and prioritize projects.

- Address root problems. Low-capacity communities are often economically dependent on farming and other natural resource sectors associated with volatile revenue. By strengthening policies that encourage economic diversification, state and federal policymakers can help communities generate predictable local revenue needed for infrastructure and adaptation.

On the other hand, rather than hiring more people to interpret ever-more complex programs, or regionalizing them out of the community’s direct authority (via “urban-rural partnerships”), how about considering simplifying requirements at the front end.

Inquiring minds might wonder why there has been only limited use of TFPA and GNA in this area, compared to other places, and how (or if) this bill would help that (other than providing funding?)

**************************

Jon posted this news story in a comment yesterday, and I think it’s innovative enough to deserve its own post. We’ve talked about what “co-management” means, and how it’s interpreted. I think we have to look very specifically at what is meant. Let’s develop a range of options- these are just some. Talking more? Sharing information? Using traditional ecological knowledge? Prioritizing projects of interest to Tribes? Giving Tribes’ views on management priority over other members of the public? Giving projects supported by Tribes some relief from litigation? Giving Tribes a seat at the table during legal settlements involving projects of concern? Conceivably, 1, 2, 3 and 4 are called co-stewardship, and all Forests (and the BLM) are supposed to be doing those, and they don’t require specific treaty rights or specific legislation.

WASHINGTON (KTVZ) — Rep. Earl Blumenauer and Senator Ron Wyden, along with Senator Jeff Merkley, reintroduced the Wy’east Tribal Resources Restoration Act. The legislation directs the U.S. Forest Service to partner with the Confederated Tribes of the Warm Springs to develop a co-management plan for agreed-upon Treaty Resource Emphasis Zones.

The legislation would establish one of the first placed-based co-management strategies in the nation.

It was introduced last Congress, and had a hearing in the Senate Committee on Energy and Natural Resources.

“Indigenous communities have been responsible stewards of Oregon’s lands and wildlife since time immemorial. We must do more to capitalize on their leadership in our conservation efforts—not just because the federal government has a moral obligation to do so but because we will not be successful without them,” said Blumenauer. “Tribal co-stewardship represents 21st?century public lands management.”

“The Confederated Tribes of Warm Springs have generations-long knowledge of best ecological practices and treaty rights with the federal government that must be protected,” Wyden said. “This legislation would secure both goals in the Mount Hood National Forest by giving the Tribe an important voice and role in the management of its precious cultural resources.”

“The Confederated Tribes of Warm Springs are the largest neighbor to the Mt. Hood National Forest and are essential in maintaining and protecting the region’s cultural and ecological resources,” said Senator Jeff Merkley. “This legislation is a critical step in fulfilling our treaty and trust responsibilities to the Warm Springs community by creating a framework for them to take an active role in co-managing the forest and utilizing their knowledge, traditions, and expertise to improve forest management.”

The Wy’east Tribal Resources Restoration Act:

· Directs the U.S. Forest Service to develop a co-management plan with the Confederated Tribes of the Warm Springs to protect and enhance Tribal Treaty resources and protect the Reservation from wildfire within agreed-upon “Treaty Resources Emphasis Zones.” These zones are areas within the Mount Hood National Forest subject to the Warm Springs-Forest Service co-management plan;

* Requires implementation of the Cultural Foods Obligations, which were included in the Public Lands Management Act of 2009 but have never been implemented;

· Integrates traditional ecological knowledge as an important part of the best available scientific information used in forest and resource management areas within the Zone;

· Authorizes $3,500,000 in annual appropriations and the use of existing Forest Service revenue to ensure the Tribe is a full participant in management.

Click here for bill text. Click here for a one-page fact sheet.

“We are grateful to Rep. Blumenauer and Senator Wyden for this legislation. Warm Springs people have cared for the land since the Creator placed us here, and this legislation will help reconnect Wy’east to its original inhabitants and integrate traditional ecological knowledge into federal land management. The bill would allow the Warm Springs Tribe to improve fish and wildlife habitat, reduce forest fuels and wildfire risk in the borderlands of our Reservation — an area designated as a priority fireshed by the U.S. Forest Service.? The result will improve forest and wildlife health for the benefit of all Oregonians,” said Warm Springs Chairman Jonathan Smith.

Note that all the folks quoted, except for Sustainable Northwest, are all recreation outfits of various kinds.

I thought that this was interesting, it seems to relate to the Zones of co-management and echoes the 2001 Roadless Rule (except off the top of my head the RR did not have the language “promote fire resilient stands.”

(C) include requirements that no temporary or permanent road shall be constructed within a Zone, except as necessary

‘‘(i) to meet the requirements for the administration of a Zone;

‘‘(ii) to protect public health and safety;

‘‘(iii) to respond to an emergency;

‘‘(iv) for the control of fire, insects, diseases, subject to such terms and conditions as the Secretary determines to be appropriate; and

‘‘(D) to the maximum extent practicable, to meet the purposes of this section, provide for the retention of large trees, as appropriate for the historic forest structure or promotion of fire-resilient stands.

Maybe I’m reading this wrong, but it sounds like the intention is to have specific areas on the Forest to be co-managed for various reasons including wildfire resilience, without temporary roads. Which doesn’t really seem like co-management, suppose the Tribe wants to move material offsite for whatever reason? It seems like co-management within parameters the politicians have decided with the same analysis and litigation processes as currently exist. So what’s the advantage to the Tribe, or to the taxpayer other than more discussion and integrating TEK (everyone’s supposed to do that), and for which a statute is not needed? Actually it seems more restrictive to wildfire resilience than the current situation, based on the roadless-like requirements, so that’s puzzling.

Finally, I guess another question, perhaps more philosophical, is “suppose Tribes’ ecological knowledge is that temp roads are useful”? Maybe it’s not Traditional, but then who decides? Seems like sovereignty would say that Tribal views and knowledge are important, no matter what over what time frame this knowledge was developed. Here’s a USFWS definition of TEK.

Traditional Ecological Knowledge, also called by other names including Indigenous Knowledge or Native Science, (hereafter, TEK) refers to the evolving knowledge acquired by indigenous and local peoples over hundreds or thousands of years through direct contact with the environment. This knowledge is specific to a location and includes the relationships between plants, animals, natural phenomena, landscapes and timing of events that are used for lifeways, including but not limited to hunting, fishing, trapping, agriculture, and forestry.

There might be an implicit colonizer bias here that Indigenous knowledge stopped being valuable when immigrants shared new technologies. Like other humans, Tribal folks adapt new ideas and technologies that work for them- in ways that might be different from the technologies as introduced. Think horses, woodstoves, and temp roads. What would a court case look like in which a Tribe argued that temp roads, done their way, used the best available science based on Current Indigenous Ecological Knowledge?

Anyway, I could have gotten this wrong, and I realize that there is a theatrical element to proposed legislation, so would appreciate thoughts of folks who know more.

Article in the4 NY Times today. I hope this link works — I’m allowed to “gift” articles….

They Shoot Owls in California, Don’t They?

An audacious federal plan to protect the spotted owl would eradicate hundreds of thousands of barred owls in the coming years.

Excerpt:

Crammed into marginal territories and bedeviled by wildfires, northern spotted owl populations have declined by up to 80 percent over the last two decades. As few as 3,000 remain on federal lands, compared with 11,000 in 1993. In the wilds of British Columbia, the northern spotted owl has vanished; only one, a female, remains. If the trend continues, the northern spotted owl could become the first owl subspecies in the United States to go extinct.

In a last-ditch effort to rescue the northern spotted owl from oblivion and protect the California spotted owl population, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service has proposed culling a staggering number of barred owls across a swath of 11 to 14 million acres in Washington, Oregon and Northern California, where barred owls — which the agency regards as invasive — are encroaching. The lethal management plan calls for eradicating up to half a million barred owls over the next 30 years, or 30 percent of the population over that time frame. The owls would be dispatched using the cheapest and most efficient methods, from large-bore shotguns with night scopes to capture and euthanasia.

This story map is nicely done. Shout out to the folks who produced it!

***********************

If you, readers, have something you are proud of.. please send it in and I will share. Some FS people do this, but as with our piece on SERAL, there are many great stories out there. And I know of some great work, that I can’t share because some Powers Who Decide are hinky about sharing with the public. Hopefully, that is short-term and election-related.

*************************

Below, I excerpted one paragraph from a few of the projects to give you a flavor. These projects have to do with wildfire resilience in one form or another, and there are others that deal with watershed restoration, check them out! I particularly like the one with free firewood for Tribal members from wildfire salvage.

You’ll remember that a few weeks ago, Cody Desautel (of the Intertribal Timber Council) testified at the House Natural Resources Committee, including difficulties carrying out joint projects with the Forest Service due to litigation. I wonder whether folks have thought about some kind of litigation carve-out for joint projects with Tribes, who conceivably have some treaty rights (different for different now-Forests).

The partnership combines resources from the Cow Creek Umpqua Tribe and Umpqua National Forest to co-implement thinning and fuels reduction treatments on the Tiller Ranger District through a three-phase partnership called the Johnnie Springs Project. Phase one started in October of 2023 and authorizes the Tribe to implement fuels reduction treatments along 17 miles (618 acres) of road in areas where the Forest has already completed environmental analysis. Phase two has identified additional areas within the Johnnie Spring project area that are adjacent to Tribal trust lands and in need of active management. Phase two proposed treatments includes an additional 12 miles (436 acres) of roadside fuels treatments and 570 acres of small diameter tree thinning units. Phase three is proposed as a planning phase, in need of additional NEPA analysis to move forward. Currently, Forest and Tribal managers are looking at opportunities to analyze new acres available for commercial thinning and opportunities for additional roadside thinning work within the current Johnnie Springs planning area. Additionally, in phase three, the Umpqua National Forest and Cow Creek Umpqua Tribe will evaluate other portions of the Tiller Ranger District for future co-stewardship opportunities. All phases include a prescribed fire element, ensuring opportunities to reintroduce healthy fire back to the landscape is considered when the right environmental conditions are in place.

The Yakama Nation requested to enter into agreement under the Tribal Forest Protection Act to coordinate and collaborate with the United States Forest Service on the South Fork Tieton Project on Yakama Nation Ceded Lands. The project was funded with the Central Washington Initiative as part of the Bipartisan Infrastructure Bill with the goal to complete planning and environmental analysis on 40,000 acres with a 189,500 acre fire shed. This project will focus on wildfire risk reduction.

The Trail Project is located in Pend Oreille County in northeastern Washington State, four miles north of Newport. Restoration work will include a suite of tools, over the next 10-15 years, to accomplish the goals of the project. For example, commercial and non-commercial thinning of trees and prescribed fire will increase diversity and resilience to forest stands, decrease potential for insect and disease, maintain more characteristic open tree stands to increase tree vigor by reducing competition for resources, provide economic opportunity from the surrounding community, while also reducing fuels and limiting the severity of wildfires. Open tree stands will improve forest health and increase forage for wildlife by allowing sunlight to reach the forest floor.

The Nez Perce Tribe Forest and Fire Management Division leads this program to supply free firewood to more than 160 tribal elders, disabled, and even single parents leading into and during the cold winter months. This program depends on a steady supply of firewood and is an important way that the Tribe provides heat sources throughout the winter for their elders and other eligible tribal members.

Through this partnership the Tribe will be able to provide approximately 60 truckloads of firewood to elders and others in need within the Nez Perce Tribe community. This agreement is part of the agency’s overall commitment to strengthen nation-to-nation relationships and enhance co-stewardship of National Forest lands with American Indian Tribes. Together, the Wallowa-Whitman National Forest and Nez Perce Tribe are fostering mutual trust and building relationships that contribute to improving forest management and restoration activities in a way that reflects mutual goals, values, and objectives.

A friend sent this, from The Hotshot Wakeup…. Excerpt:

A Forest Service memo went out this week after I reported on the “strategic pause,” which said the following:

“We are still under a 30-day hiring pause while the WO “Washington Office” determines how many employees we have and what the cost is.”

Question about how USAJOBS works. A forestry student of mine applied for a technician job with a federal agency. The student was very well qualified, has a related associate’s degree, relevant work experience, and had done related volunteer work for an NGO (a watershed council) in the same watershed, plus had the president of the NGO as a reference. The student also reached out to the agency’s staffer who would make the hiring decision and was well received. The student now has received an email from “usastaffingoffice” saying that “You are tentatively eligible for this series/grade combination based on your self-rating of your qualifications.” But: “You have not been referred to the hiring manager” for the position, and “If you were not referred, you were not found to be among the most highly qualified for the position.” Naturally, this very well qualified applicant is disappointed not to be selected for an interview with a real person.

Questions:

Did a human being evaluate the student’s application at any point? Or was it completely automated?

Can hiring managers request that USAJOBS re-evaluate the student’s application?

The Chief mentioned the Community Wildfire Protection Program, which reminded me of this article (thanks to Nick Smith!). Bay Nature is sensitive about my excerpting too much from their pieces but the piece is available without a paywall here. There’s also a great chart showing how long it took for different grants to go through.

The Community Wildfire Defense Grants are a brand-new program that was kickstarted by the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law last year. Nationwide, the program will provide $1 billion dollars over five years to help communities manage their fire risks. Grants are meant for the communities in greatest need, and applicants are weighed by socioeconomic factors as well as fire risk—work happens on private or tribal trust lands, not federal properties. “Some people might be saying, ‘It’s delayed.’ But on the other hand, it’s a new program that they had to stand up very quickly,” says Evan Burks, spokesperson for the USFS. “And it’s been an absolute game-changer.”

Galleher and his colleagues weren’t the only ones who encountered delays. Elsewhere in Plumas County, the Feather River Resource Conservation District, a nonregulatory local agency that works on post-fire restoration, waited 10 months for its $8.5 million grant. Outside of Plumas, the Forest Service says, three of California’s 33 grantees have yet to receive awards totaling over $10 million—and it’s been a year and counting since that round of awards was announced. These include northern California communities in Mendocino, Trinity, and Kern. On average, grants took about 250 days, or about eight months, to execute.

“High-risk communities have to fret through fire seasons, while they just sort of hope to God that they don’t have a fire come through the neighborhood,” says Hugh Safford, a former regional ecologist who left the Forest Service in 2021. He now works on forest resilience as chief scientist at a tech startup, Vibrant Planet, and holds an ecology research position at UC Davis. “It means that they’re gonna go another fire season without having the work done.”

USFS officials say grants were held up due to small, bureaucratic delays—such as checking signatures were valid, or budget back-and-forths. But Adrienne Freeman, a spokesperson for the grant program, also acknowledges two factors: an agency-wide staffing shortage, and a lack of an external clearinghouse to get the money moving on the beleaguered Forest Service’s behalf. “The Forest Service, [which] has extremely limited capacity, is doing all of these grants. So, fundamentally, it’s gonna be a challenge,” Freeman says. Some states have taken over administering the grants, and CalFire has distributed some federal money originating from the USDA. But for this round of funding, the state of California opted out, putting the onus back on the federal government.

Safford likens the funds to water pouring into these communities—the nozzle that they’re coming through just isn’t big enough. “It has a really big opening where the federal government has poured in billions and billions,” he says. “It’s stacked up and overflowing at the top but there’s nothing coming out of the bottom.”

So all that was interesting, and here’s an interesting on-the-ground perspective about post-fire treatments. Each forest’s condition is different post-fire.

“In a large amount of the areas we work in there is 100% tree mortality,” Hall says. “Just completely cooked.” These are rural areas, at places where dead trees meet with burned-down residences—but despite the lack of green, these areas are presently just as much of a fire risk as the unburned areas—if not more. The ground is dry. The smoked trees, like charcoal at the heart of a hearth, are ready to rekindle at the smallest spark. When a reburn goes through a patch like this, “It’s hotter and quicker,” Hall says. “There’s not a lot of smoldering because the material is so combustible. So [fires] burn quick and move through fast.”

Ideally, Hall says, you take a crew into the dead zone within the first year of a devastating fire. At that stage, you can still use herbicides and hand-held tools to clear the burned trees and young shrubs. But when rot starts to set in, branches will weaken. The canopy becomes a hazard of its own. “After four years, large trees become really dangerous,” Hall says. “Your only hope is to maybe knock them over with an excavator.”

When the federal funds finally arrived in January, the ground in Plumas was snowy, and too wet for tree removal to begin. Hall plans to start the project in the fall instead—a little more than three years since the Dixie Fire. He doesn’t fault the Forest Service for the long delays, saying it’s “pretty darn typical” of a federal agency to be slow, and adds that the conservation district’s been managing fine with other sources of funds.

They’ve done this before: remove dead trees and brush from private property, and then step in to replant the forest with baby ponderosa pine, incense cedar, sugar pine, and Douglas fir. That’s the way to break the burn cycle, Hall says.

But he is worried. There’s an eight- to 12-year post-fire window, he says, during which the dead trees and the shrubs growing around them pose a serious threat of reburning—and, with large wildfires coming more frequently nowadays, they are more likely to do so. That’s the real clock they’re up against. “It can burn again,” he says. “It will burn again.”

My thoughts as admittedly a non-Fire person.

* News for me was that “PODS which should be nearly complete in the West”. I’m not sure the link between their completion and the public knowing where they are is complete. Would appreciate observations of others.

* I’m also not sure I appreciate this “Our focus must remain on achieving our “Wildfire Crisis Strategy” landscape restoration goals, while fulfilling our leadership role in emergency response.”

I wonder if he meant the same thing as “During this fire season, our priority remains the protection of people, communities, watersheds and wildlife habitat, including old growth, while continuing to work toward our landscape restoration goals.” I’m not as sensitive about this as some people are, but if I lived closer to a National Forest, I probably would be. “Emergency response” sounds kind of vague.. I’d like to see human lives, homes, communities have higher prominence (although I know with fire-fighters they do). Maybe that’s just the bureaucratic writer in me.

*I also do wish the Forest Service would determine what counts as good fire versus bad fire, as otherwise if the FS believes managed wildfire is good and promotes it, “Increasingly, we see the potential for fire to increase landscape resilience when conditions permit” and our climate/wildfire folks see only total acres burned, they are likely to attribute the increased acres to climate change.

Below is the letter text, and here is a link.

Last year we significantly progressed toward achieving many of our top Agency priorities; I’m proud of the efforts of each and every employee. The tremendous achievements of 2023 set the stage for a promising 2024. Our collective commitment and resilience turned vision into action. We faced challenges head-on, with significant contributions from employees, at all levels, at home and abroad. Our historic achievement to treat over 4.3 million acres of hazardous fuels underscores our dedication to accelerate strategic investments and intentionally allocate expertise.

All signs point to a very active 2024 fire year. We will continue safe, effective initial attack to protect communities, critical infrastructure, and natural resources. In doing so, I expect all

leaders to put our people first as they put themselves in harm’s way to protect communities and landscapes. Your role as leaders is pivotal to sustaining our organization and ensuring our employees feel safe—psychologically, physically and socially. Safety is one of our core values. As such, I expect us to remain committed to a safe and resilient workforce which also means continued emphasis on employee well-being. Setting clear expectations for resource availability is vital to managing employee mental and physical fatigue and balancing wildfire response demands with hazardous fuels reduction needs. As I stated last year, we will continue to support and defend any employee who is doing work to support our mission. I also expect us to continue to address instances of harassment or bullying immediately and reflect these policies in our work environment and in your delegation letters.Acknowledging the inherent risks in suppressing wildfires, I expect us to continue to use all available tools and technologies to ensure proactive prescribed fire planning and implementation, fire detection, risk assessments, fire response, and post-fire recovery. Every fire will receive a risk-informed response; we know the most effective strategies are collaboratively carried-out, at the local level. I expect all line officers and fire leaders to be inclusive with stakeholders during pre-season collaboration. This builds a common understanding of strategic risk assessments, strategic actions to protect identified values at risk, and expected fire response. The best research-informed tool we have for doing this is Potential Operational Delineations (PODs). Pre-planning with Potential Operational Delineations (PODs), better forecasting and knowledge of existing fuel treatments, and risk-sharing dialogue with community members, stakeholders, and cooperators, will help us make informed decisions that balance resource objectives with safety and community protection. I expect all line officers and fire managers to make use of PODs, which should be nearly complete in the West, or alternative science-based means for ensuring effective pre-season collaboration. When looking at using all tools in the toolbox, line officers should also ensure they are working in close collaboration with affected partners like industry, including the ability to mobilize resources in a collaborative manner through mechanisms like the National Alliance of Forest Owners Fire Suppression Memorandum of Understanding (MOU).

As outlined in the National Cohesive Wildland Fire Management Strategy Addendum Update, we will depend on research to inform our use of both planned and unplanned fire, and natural ignitions. This year, Regional Foresters will again approve or disapprove use of natural ignitions as a management strategy during Preparedness Levels 4 and 5, in accordance with the Interagency Standards for Fire and Fire Aviation (Red Book). Increasingly, we see the potential for fire to increase landscape resilience when conditions permit.

Our focus must remain on achieving our “Wildfire Crisis Strategy” landscape restoration goals, while fulfilling our leadership role in emergency response. In 2023 the agency built a strong foundation to help us achieve these goals, including using emergency authorities to support the “Wildfire Crisis Strategy,” releasing the National Prescribed Fire Resource Mobilization Strategy, and “A Strategy to Expand Prescribed Fire in the West”, establishing the Community Wildfire Defense Grant Program, and expanding partnerships through our Keystone Agreements. I expect us to lean into these innovations in 2024; but I am also challenging all of us collectively to keep pushing forward to unlock new innovations. This means viewing our landscapes holistically together with partners; truly being inclusive by inviting new partners to the table; and learning from our Tribal partners and their indigenous ecological knowledge gained from managing fire since time immemorial.

To keep moving forward on our journey to destigmatize mental health and wellness support, we will continue to offer care services including Critical Incident Stress Management, Casualty Assistance and Employee Assistance programs. Access to culturally competent clinical care for wildland firefighters is something the Joint Wildland Firefighter Health and Wellbeing Program with the U.S. Department of the Interior will continue to develop. Through this program, clinician-led mental health education sessions will be made available for units before the height of the fire year to reinforce the importance of employee wellbeing. Claims processes and employee coverage for presumptive illnesses have changed and I expect leaders to ensure they and their employees receive sufficient information and training. We must be ready to personally engage in support of our employees needing those services.

It is my expectation we will adhere to the seven tactical recommendations of the 2022 National Prescribed Fire Program Review. Agency Administrators will continue to authorize a new ignition for each operational period while considering fuels and potential fire behavior in areas adjacent to the planned burn and documenting regionally relevant drought metrics. A declared wildfire review will be the standard approach whenever a prescribed fire is declared a wildfire. Forest Service Manual 5140 and the NWCG Standards for Prescribed Fire Planning and Implementation, PMS 484, will dictate declared wildfire reviews. These combined efforts, and remaining anchored in our core values of safety, interdependence, conservation, diversity, and service, are paving the path to a future where the Forest Service remains the world’s expert in fire management and a trusted employer of choice.

In closing, I thank you for your commitment to put people first. We will stay the course and continue to fight for a permanent pay increase for firefighters, as well as pay stability for all incident responders. I also thank each of our employees for their continued dedication to the agency mission and service to the Nation.