These are a few things missed between the last Forest Service summaries. Links are to court documents or articles.

FOREST SERVICE COURT DECISIONS

Unite the Parks v. U. S. Forest Service (9th Cir.)

On January 25, the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals ordered a district court to reconsider its denial of a preliminary injunction against 31 logging projects in endangered Pacific fisher habitat on the Sierra and Sequoia National Forests. The district court decision had not properly taken into account recent information. (The 9th Circuit did not issue its own injunction, however.) (The article includes a link to the opinion.)

Neighbors of the Mogollon Rim v. U. S. Forest Service (D. Ariz.)

On January 26, in a case filed by intermingled private landowners, the Arizona district court upheld the decision to restart livestock grazing on inactive allotments and the Heber-Reno Sheep Driveway on the Tonto National Forest with a new allotment management plan and term permit based on an EA. The court found no violation of NEPA or ESA. It found the decision consistent with the forest plan even if it did “not move the Tonto National Forest towards the long-term resource goals set out in the Forest Plan,” because, “the Proposed Action would not have a significant adverse effect on these elements, and because, “grazing is a permissible and contemplated use under the Tonto Forest Plan.” (I don’t see the logic here, since neither of these reasons address the issue raised by plaintiffs.)

SETTLEMENT

Center for Biological Diversity v. Bernhardt (D. Nevada)

On January 19, the parties settled this case, allowing the implementation of the Lee Canyon Ski Area Master Development Plan on the Humboldt-Toiyabe National Forest (introduced here). The settlement agreement calls for habitat buffer zones where construction of mountain bike trails would not be allowed under most circumstances and a $250,000 pledge from the resort to UNLV for research.

NEW CASES

Strawberry Water Users Association v. U.S.A. (D. Utah).

On January 3, plaintiff sued the Forest Service for allegedly letting two lightning-ignited wildfires burn on the Uinta-Wasatch-Cache National Forest in 2018, resulting in $200 million in damage to its water infrastructure. (Details on the fires are available here.)

Center for Biological Diversity v. Haaland (D. Minn.)

On January 25, five plaintiff organizations sued USDI, the Forest Service, Fish and Wildlife Service, and the Army Corps of Engineers over decisions to exchange lands and permit the PolyMet copper mine on the Superior National Forest based on a 2016 Biological Opinion’s conclusions that the Project is not likely to jeopardize the Canada lynx, gray wolf, or northern long-eared bat, and is not likely to adversely modify the designated critical habitat for the Canada lynx or gray wolf. (The article includes a link to the opinion.)

Meanwhile, a second mine on the Superior National Forest was derailed on January 26, when the Interior Department’s principal deputy solicitor, wrote in a legal opinion that the Trump administration fell short in its legal obligations by conducting an inadequate environmental analysis and by sidestepping the Forest Service in its decision-making regarding the proposed Twin Metals project.

OTHER AGENCIES

Friends of the Earth v. Haaland (D. D.C.)

On January 27, the District of Columbia district court vacated a sale of 1.7 million acres of oil and gas leases in the Gulf of Mexico because the Interior Department miscalculated the greenhouse gas emissions from drilling. It held that the 5-year program EIS should not have concluded that emissions would be higher under the no-action (no drilling) alternative because, “the record in this case includes papers from the Stockholm Environment Institute that underscore the likely decrease in foreign consumption and provides a methodology for translating the reduction in barrels of oil into a reduction in greenhouse gas emissions…” (my emphasis). (The question of substitution effects has come up on this blog.) (Here is an article discussing the case.)

Louisiana v. Biden (W.D. La.)

However, on February 11, the Western District of Louisiana enjoined an Executive Order that would have required government agencies to also account for the social benefits of reducing carbon pollution, such as changes in net agricultural productivity, human health, property damage from increased flood risk, and the value of ecosystem services. The court held that, “the President lacks power to promulgate fundamentally transformative legislative rules in areas of vast political, social, and economic importance,” he failed to follow rulemaking procedures required by the APA, and the estimates included in the order are arbitrary and capricious.

Bradford v. U. S. Department of Labor (D. Colo.)

On January 24, the Colorado district court dismissed a lawsuit filed by Colorado rafting companies seeking to block a new rule that raised the minimum wage for federal contractors to $15 an hour. (The article includes a link to the opinion.)

ESA LISTING BONUS

On January 25, the U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service proposed listing the Sacramento Mountains checkerspot butterfly as an endangered species under the Endangered Species Act. Primary threats include unregulated off-road vehicle use and fire suppression on the Lincoln National Forest. (Comments are due march 28.) (The article includes a link to the Federal Register Notice.)

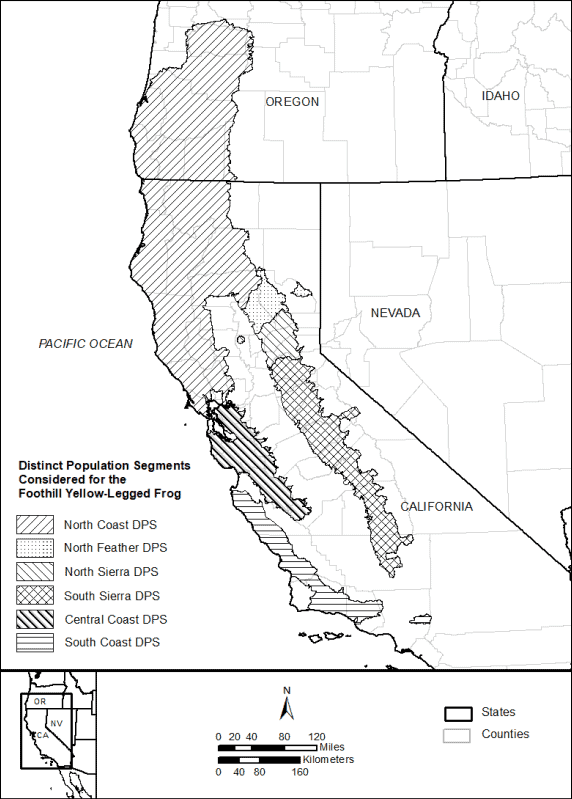

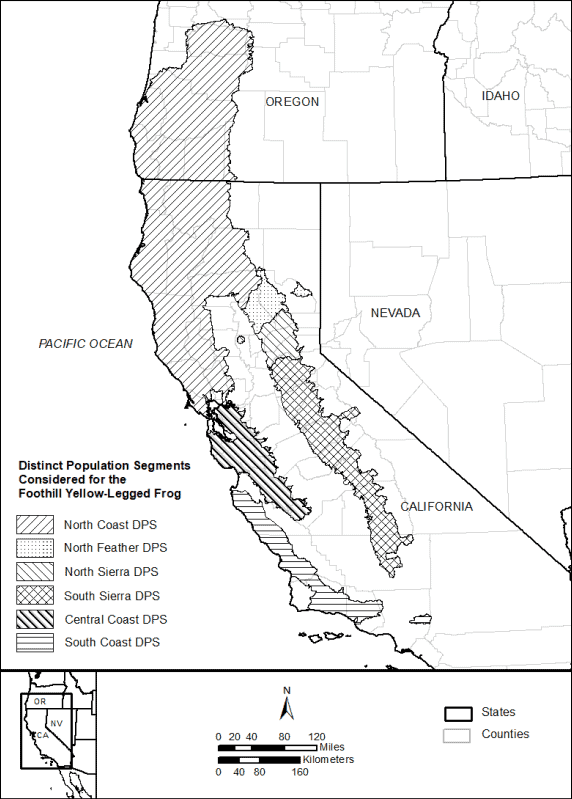

On December 27, 2021, the U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service proposed listing four of six distinct population segments (see map) of the foothill yellow-legged frog under the ESA – the South Sierra and South Coast DPSs as endangered and the North Feather and Central Coast DPSs as threatened. Logging and grazing are among the threats to the species, and the North Coast and North Sierra populations were not listed in part because of the Forest Service requirements for sensitive species (which will go away when forest plans are revised), and because, “the species in northern portions of California and the species’ range in Oregon on National Forest or BLM lands currently receive protection through conservation measures and best management practices under the Northwest Forest Plan’s Survey and Manage program” (which is currently required by forest plans). (Quoting the Federal Register Notice linked to this news release.) (The comment period is closed.)