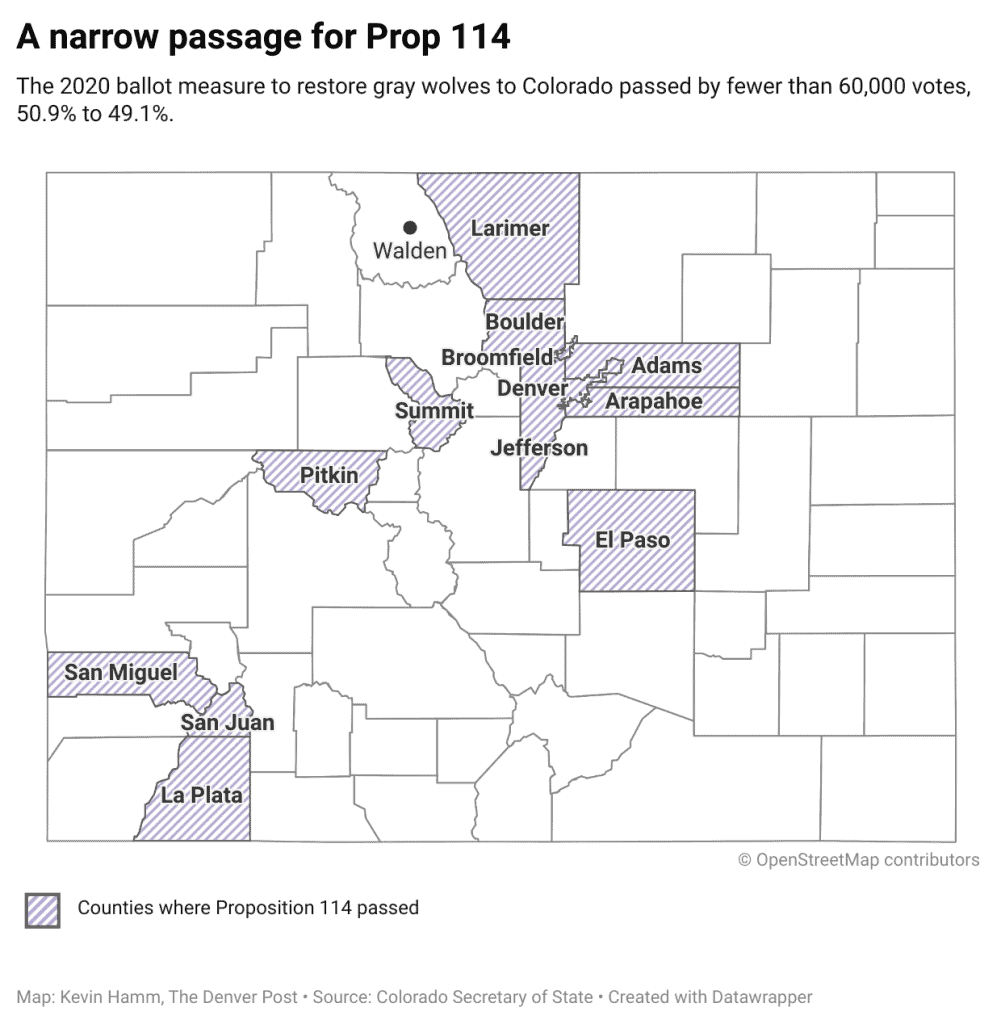

This Denver Post story by Conrad Swanson is a really excellent story on current wolf issues in Colorado, considering a variety of perspectives. For those of you who haven’t been following this issue, there are two things going on. First, there was an initiative on the ballot to reintroduce wolves.. You can see who voted for it, and to whom the negative impacts will occur, in the map above.

Meanwhile the wolves were already moving down from Wyoming, and people are dealing with them. It appears that people have different feelings about “wolves that are imposed by fiat” versus “wolves that made it on their own”, which to me is a pretty interesting twist on the wolf debates.

Gittleson said Jan. 26 that state and federal officials flew out an electric fence special for his property. They set it up in a day or two but then high winds in the area knocked parts of it down. He expressed concerns that wolves could jump over barriers but that wouldn’t make a difference if the fence was stuck on the ground anyway.

……….

Ranchers aren’t paid for injured livestock, Uriarte said. Nor are they paid for the additional animals those killed could have birthed. Or for livestock pregnancies that end prematurely due to the stress of wolf packs living nearby.

Idaho has another $139,000 from that federal grant, Uriarte said, which can supplement ranchers’ efforts to prevent wolf attacks.

Trail cameras, noisemakers, alert systems and even additional hands on the ranch, can qualify for that reimbursement, Edmondson said.

Even more money could be available in Colorado, Malone said. Not only are those federal grants available but the state earmarks more than $1.2 million each year to reimburse ranchers and farmers for livestock killed by wildlife and prevention methods.

In 2019, Colorado Parks and Wildlife received $1.28 million for that purpose and spent just over half at $686,291, budget documents show.

That money can’t currently be used for wolf attacks, Malone said, but a small tweak to the language behind the funding could allow it. In addition, other resources like nonprofits exist to teach ranchers how to be more sustainable and avoid conflicts with wolves, she said.

“Your life has to change a little,” Malone said of ranchers. “It doesn’t have to change that much and it will change for the better.”

With all due respect to Ms. Malone, I don’t think it’s necessarily going to be better for them or their animals. I would have asked her how, exactly, that works.

Several high-altitude Angus cattle surround a cow wounded in a wolf attack the evening of Jan. 17, 2022, on Don Gittleson’s ranch, outside Walden. Gittleson was forced to put the cow down later that day.

They attacked a pair of cows on Don and Kim Gittleson’s ranch sometime on the night of Jan. 17. One of the black Angus, bred specifically for life at high altitudes, would recover but the other had to be put down later that day. Not by lethal injection, Don Gittleson told The Denver Post. Better, quicker to shoot her.

The pack attacked again the next morning. Kim Gittleson said they heard howling and rushed out to the pasture where they found another dead cow, mostly eaten. The pack had howled, she said, as though they were celebrating the kill.

And they’ll be back, she said.

“The wolves know where our cows are,” she said. “It’s like we’re their grocery store.”

Many other residents in Walden, the seat of Jackson County and its only incorporated town, seem to agree.

Ranchers, business people, barflies and parents say they fear the eight wolves living on the outskirts of town. They shake their heads and tally the dead on their calloused fingers. Three cows and two dogs, most agree. More are sure to follow, they say. Some parents say they’re afraid to let their children wander alone.

Not only do the people of Walden say they feel helpless as the wolves endanger their livelihoods, tourists and their outdoor lifestyle but they also feel ignored by state officials charged with managing the apex predators, which were hunted to near extinction generations ago.

If nothing changes, they say, other small, ranching communities and farming towns on Colorado’s Western Slope can also expect to lose livestock and business when state officials begin reintroducing gray wolves to the forests next year.

Ecologists, scientists and reintroduction advocates say the fears are understandable but rooted in a lack of familiarity with wolf behavior and the data collected elsewhere. But they, too, feel ignored by state officials and insist that the Department of Natural Resources should do more to buffer the people of Walden from the wolves while still protecting the endangered species.

I’m feeling a great sympathy for DPW here, who didn’t actually support the initiative, as I recall. Now they are blamed by both sides for not doing it right.

Fletcher said he would prefer to live alongside the wolves. But he understands that they represent a threat to his livestock, pets and potentially his family and said he’d rather take a proactive management approach than a reactive one. As things are, he’s not sure whether he’ll be able to allow his cows to calve in the pasture or if they’ll have to relocate, which would increase costs dramatically.

Earlier this month, Colorado Parks and Wildlife Commission unanimously gave ranchers permission to haze, or frighten, wolves away from their properties.

Generally, hazing is understood to be anything that doesn’t kill or injure the wolves, said state Species Conservation Program Manager Eric Odell.

Fletcher gave thanks for the commission’s move but said it’s still not enough for him to be able to protect his ranch. Atencio and Don Gittleson said they’re still unclear on what they can or can’t do.

Propane cannons and rubber bullets could scare the wolves off, Atencio said. But one wrong shot could mean an injured or a dead wolf, which could carry with it a $100,000 fine, a year in jail and loss of hunting privileges for life.

Ranchers can’t watch around the clock, Atencio and Don Gittleson said. Nor can they afford to hire more hands.

The Gittlesons work their ranch with their two sons and a grandson. They own fewer than 180 cows. Every lost cow, every lost dollar counts.

But realistically, Phillips said wolf packs don’t represent a problem for the industry at large, though the losses sting more for smaller ranchers like the Gittlesons.

We recognize this argument…”see it’s not really a problem because if you average it out over a lot of other people, people who aren’t you , it’s not a problem!” We’ve heard that argument quite a bit around other issues.

It’s fascinating that because it’s an initiative, it seems like no matter how many wolves establish naturally, DPW will still be required to reintroduce them.. regardless of what they would normally consider.

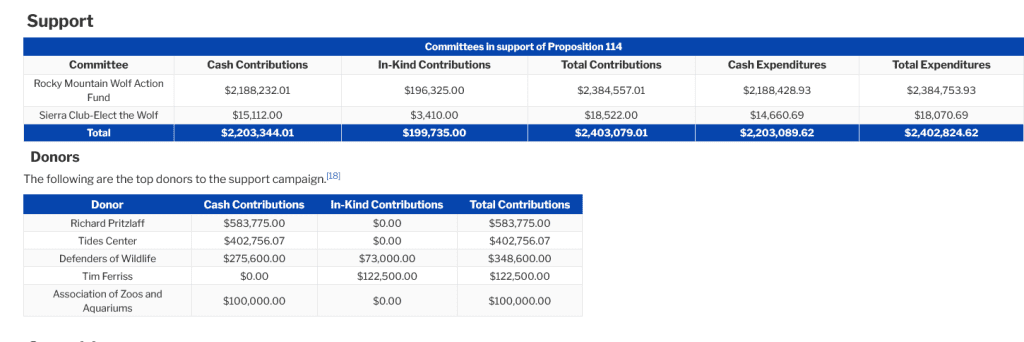

For those of you who are interested in how such an urban/rural dividing initiative came about, here’s the bucks.

And who contributes to the Rocky Mountain Wolf Action Fund? The usual dark money suspects. A person might wonder whether sowing urban/rural divisions is a feature or a bug.

And who contributes to the Rocky Mountain Wolf Action Fund? The usual dark money suspects. A person might wonder whether sowing urban/rural divisions is a feature or a bug.