SF Chronicle story..very cool graphics .. also “catching people doing something right”.

SF Chronicle story..very cool graphics .. also “catching people doing something right”.

Meyers and Christmas Valley area

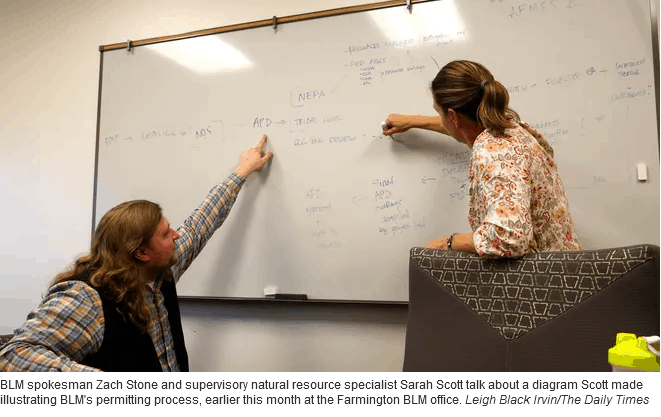

Up and over the mountains past Echo Summit and back down the ridge, the small communities of Meyers and Christmas Valley near South Lake Tahoe were well prepared for a wildfire — so well prepared that the Caldor Fire skipped over much of it.A Lake Tahoe Basin fire commission of more than 20 local, state and federal agencies that came together after the 2007 Angora Fire spent years fireproofing the area, which included several fuel treatment projects, which included prescribed burns. The commission produced a meticulous response map showing how firefighters could use those areas to their advantage, Anthony of Cal Fire said.

Large-scale treatment projects like the Caples restoration projects are very effective, Stewart of UC Berkeley said, but difficult to make happen because of the complicated processes and costs. They also often face opposition from area residents and environmentalists over the use of heavy machinery, air quality or change to the landscape, he added.

“We need to do (treatments) on a bigger scale,” he said. “Just look at the scale of these fires. Even with all the resources they threw out, they couldn’t slow these fires down.”

There needs to be a more practical approach to fuel treatments in California, Stewart added. He says agencies need to examine what’s working versus not through data and be willing involve people and ideas that can help projects scale up.

LA Times story:

Susie Kocher, forestry and natural resources advisor at the University of California Cooperative Extension, agreed.

“If you look at any of the fire maps, there’s a big gap between Kirkwood and Tahoe,” said Kocher, who was forced to evacuate her Meyers, Calif., home Monday. “That’s Caples.”

She said that due in part to its allure, the Tahoe area has been more successful than many parts of the Sierra in attracting resources for such projects.

The Tahoe Fire and Fuels Team, a multiagency coalition formed after the damaging Angora fire in 2007, said it has performed 65,000 acres of fuel reduction work in the Tahoe Basin over the past 13 years. The group also helps neighborhoods prepare for fire.

In a recent community briefing, Rocky Oplinger, an incident commander, described how such work can assist firefighters. When the fire spotted above Meyers, it reached a fuels treatment that helped reduce flame lengths from 150 to 15 feet, enabling firefighters to mount a direct attack and protect homes, he said.

“It takes both fuels reduction and active suppression in an environment like this to help the community and the forest survive,” Kocher said.

And an interview in the Sacramento Bee with Scott Stephens, fire researcher..during the fire.

How much consensus is there among fire scientists that these treatments do help?

I’d say at least 99%. I’ll be honest with you, it’s that strong; it’s that strong. There’s at least 99% certainty that treated areas do moderate fire behavior. You will always have the ignition potential, but the fires will be much easier to basically manage.

NEPA nerds Lake Tahoe is the only FS unit with its own CE as far as I know.

Lake Tahoe Basin Hazardous Fuel Reduction Projects. The 2009 Omnibus Appropriations Act (Public Law (Pub. L.) 111-8) established a CE for hazardous fuels reduction projects within the Lake Tahoe Basin Management Unit.

Within the Lake Tahoe Basin Management Unit, projects carried out under this authority are limited to the following size limitations:

a proposal to authorize a hazardous fuel reduction project, not to exceed 5,000 acres, including no more than 1,500 acres of mechanical thinning. (Sec. 423 (a))

This CE can be used if the project:

is consistent with the Lake Tahoe Basin Multi-Jurisdictional Fuel Reduction and Wildfire Prevention Strategy published in December 2007 and any subsequent revision to the strategy;is not conducted in any wilderness areas; and

does not involve any new permanent roads. (Sec. 423 (a))

A proposal using this CE shall be subject to:

the extraordinary circumstances procedures…; and

an opportunity for public input. (Sec. 423 (b))

Document this category in a decision memo (FSH 1909.15, 33.2 – 33.3). The decision memo should include a description of the efforts taking by the Lake Tahoe Basin Management Unit provide an opportunity for public input.

Cite this authority as Pub. L. 111-8, Sec. 423

Note that this is up to 5,000 acres. I just think it’s interesting and likely related to politics. It’s more important to protect some communities than others?