There seem to be more bills floating around in Congress about fire and forests and carbon than ever before. Jon Haber does a terrific job on rounding up litigation; it would be wonderful if someone (or a group) would be willing to do the same for legislation. It’s definitely more than I can keep up with. And if it is your day job, being anonymous would be perfectly acceptable. All you would have to do is find the key provisions of interest and post them.. we can discuss the pros and cons, and add relevant info, here.

We can’t count on news stories to go to the detail we’d prefer. Different reporters are interested in different things, and generally don’t provide the comprehensive view related to our interests.. so we are left with “what other people the reporter contacted thought about the bill.” Not quite as useful as the text, IMHO.

Here’s one example from E&E news..(granted the reporter mostly works on climate.. so..) interesting choice of interviewees, Chad Hanson, Tim Ingalsbee (asserting that fuel treatments of various kinds don’t work..) and a researcher from the Midwest.

But it takes more than just keeping the big trees to get fire resilience, said Jessica McCarty, a Miami University professor who studies wildfire. Operating the logging machinery can be a fire risk, and moving such equipment through the forest leaves lasting disturbances.

“If you take out everything but the large trees, you’ve probably disturbed and/or compacted the soil. Then what’s going to grow in the understory? Probably grasses and forbs. And to be quite frank, in North America, that means you have a high likelihood of invasive species,” she said.

It would be a good thing for federal agencies to shift their timber programs toward sustainable, climate adaptive practices, McCarty added. That would mean an end to clear-cutting and better incentives for more selective logging in natural areas.

I was curious about the details of this mentioned in the article..

It also creates a new federal system for subsidizing sawmills and other wood processing facilities, along with $400 million in new financial assistance. “Close proximity” to a sawmill would become a factor for agencies to consider when funding federal land restoration.

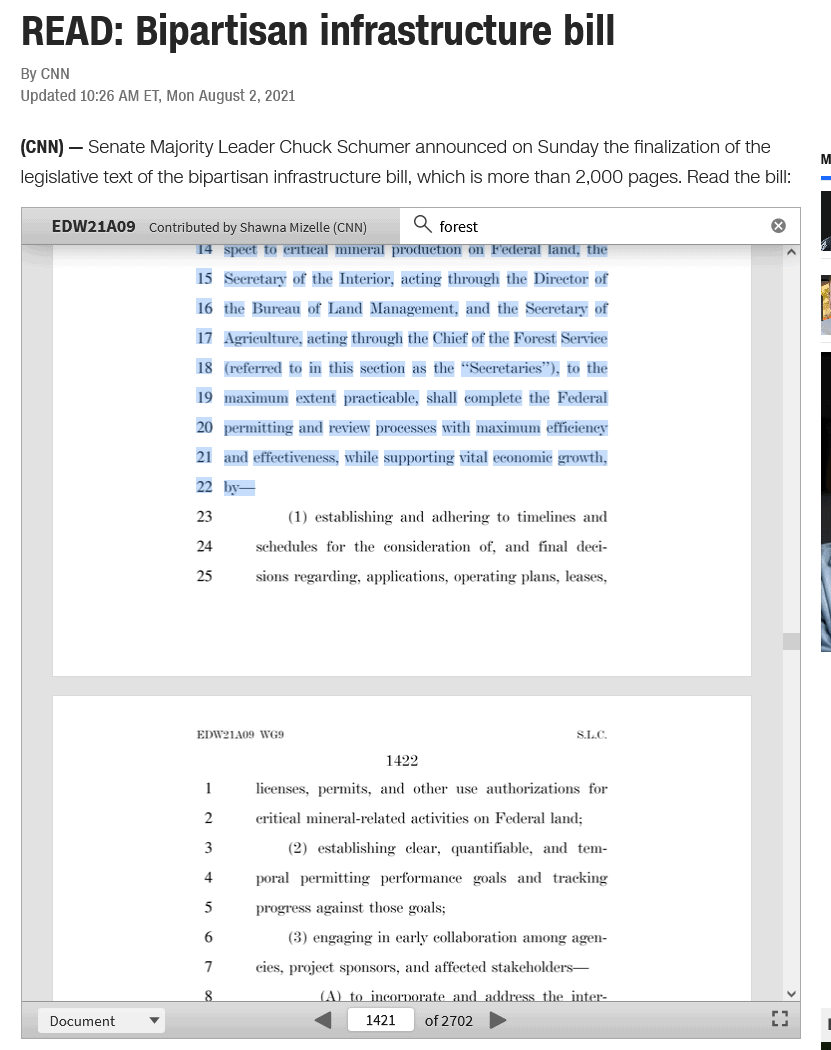

So decided to do a search on Forest. One of the first things I ran across was about permitting critical minerals, so I got sidetracked.

(e) FEDERAL PERMITTING AND REVIEW PERFORMANCE REQUIREMENTS—To improve the quality and timeliness of Federal permitting and review processes with respect to critical mineral production on Federal land, the Secretary of the Interior, acting through the Director of the Bureau of Land Management, and the Secretary of Agriculture, acting through the Chief of the Forest Service (referred to in this section as the ‘‘Secretaries’’), to the maximum extent practicable, shall complete the Federal permitting and review processes with maximum efficiency and effectiveness, while supporting vital economic growth, by— …

and it goes on at some length about how to do that.

Interesting, but searching on “forest” through more than 2000 pages is time-consuming. Now I know that there are individuals in Forest Service Legislative Affairs who do this work, but unfortunately we don’t have access to their work the same way we have access to Litigation Weekly. It would be quite a public service if that could be done, IMHO, and good press for the FS.

Anyway, until that day The Smokey Wire could really use one or more helpers in this area. Please consider it.