I mentioned that I was working on a project to find areas of agreement between environmental groups of various kinds (ENGOs) and others on a variety of topics related to restoration, fuels management and wildfires. I looked at the Climate Smart Agriculture and Forestry public comment letters that USDA requested earlier this year.

Most, but not all, of the ENGOs agreed on the general concept of increasing the pace and scale of “ecological restoration.” This is a striking level of agreement, given the extensive history of disagreements around federal land management that we see here regularly on TSW. There are also those groups whose letters said thing like “it’s a ruse to continue logging,” but it seemed more difficult or impossible to incorporate those views into an area of agreement.

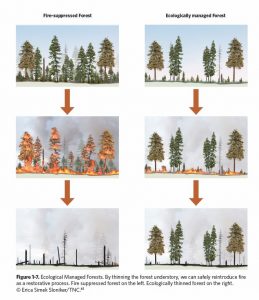

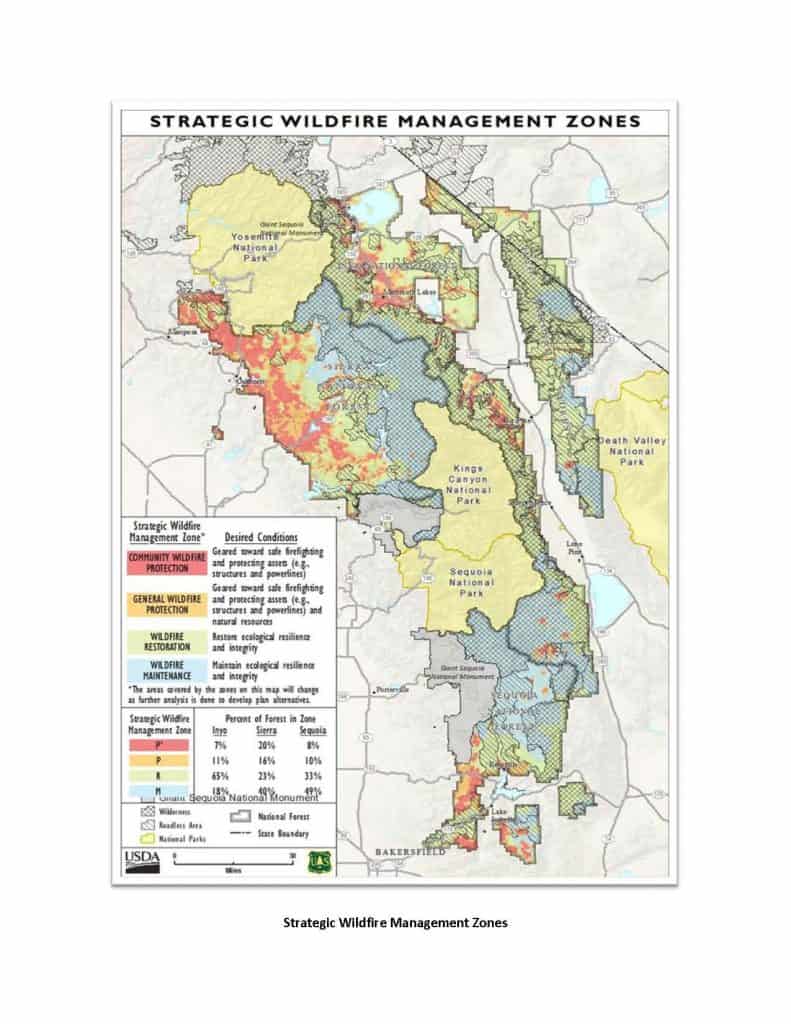

To restore historic conditions in ponderosa pine and mixed conifer forests, thinning and prescribed burning are generally accepted tools. Conveniently, these same treatments provide opportunities for changing wildfire behavior. Strategically placing restoration treatments on the landscape as described in the POD (Potential Operational Delineation)[1] process that combines local expertise and modeling to specifically support incident management can blend concern for appropriate suppression and the perceived need for restoration in these systems.

There seemed to be a difference between the Environmental Defense Fund, The Nature Conservancy and Defenders of Wildlife, all powerful political actors on the national scene.

Defenders of Wildlife (Defenders) state in their letter[2] “Rather than characterizing wildfire management as a matter solely of risk reduction, we recommend that a USDA climate-smart policy be based upon the bedrock principles of the Cohesive Strategy and seek to maintain and restore the ecological integrity of fire adapted landscapes; develop fire adapted human communities; and improve effective wildfire response.”

The Cohesive Strategy (2014)[3] never uses those words; the actual wording is: “Landscapes across all jurisdictions are resilient to fire-related disturbances in accordance with management objectives.” (p.3.) A search of the document did not yield the term “integrity.”

Now as you all know, I am a fan of using the term “resilience,” and not so much “integrity”, so I won’t further belabor the point.

Defenders later recommend (p. 17): “Develop planning and decision-making structures and processes that ensure that the highest priority areas within mixed ownership landscapes are addressed first; this would include areas around communities as well as areas that are most degraded and departed from desired reference conditions. “

It’s not clear but it sounds like they would prioritize areas most “departed from reference conditions” before PODs (these might not be “around” communities). We could call this the “departure first” view.

On the other hand, the Environmental Defense Fund has a detailed prescription[4], with perhaps different priorities than Defenders. We might call this one “safety first.”

“Our national wildfire strategy should have two priorities: 1) Protect communities in the line of fire; and 2) Reestablish natural fire patterns to protect ecosystem values and sustainably manage fuel loads. Reestablishing natural fire regimes can only be realized when fuel loads, particularly in the West, are greatly reduced using both mechanical treatments and prescribed and managed fire. Implementation will require an updated wildfire triage approach to ensure that we address the most pressing threats to communities and human lives, first.”

Similarly, The Nature Conservancy (TNC)[5] (p. 13) supports “highest priority fuels management.”

“Like the Forest Service, the Department of the Interior investments focused on highest-priority fuels management would result in boots on the ground, restored landscapes and safer communities and water supplies while providing substantial rural and tribal jobs. There are both climate mitigation and adaptation benefits to all this work.”

Perhaps they are all saying the same thing, and the different staff authors just use different words.

To me, the key question would be what exactly would need to be done, and how far away, to protect communities? Would that look like PODs? Who would be involved in prioritizing and designing the treatments, and what would be the role of “restoration” driven by historic vegetation ecologists and desired reference conditions, compared to “treatments designed to help manage fire” driven by fuels and suppression practitioners? One of the criticisms that led to PODs on the Arapaho Roosevelt, at least in the story I heard, was that the they seemed to be “random acts of restoration”. But with landscape fuels and fire knowledge, these same treatments might have been placed in a pattern to also have landscape fire management benefits. There’s also the issue of what if a community wants some fuel breaks, and they’re surrounded by tree species that aren’t adapted to fire, or are adapted to stand-replacing fire, so the whole “restoration to reference conditions” may not work for them.

And maybe this (safety first vs. departure first) doesn’t matter, as the collaborative groups whose “zones of agreement” I’ve viewed either don’t seem to see this as a dichotomy or have resolved it. That’s why I’d like to hear from others, especially those from collaborative groups, on how these two maybe different sets of priorities are worked out in practice, or if it’s even an issue on the ground.

[1] https://forestpolicypub.com/2021/05/13/changing-the-game-using-potential-wildfire-operational-delineation-pods-for-a-better-future-with-fire/; https://cfri.colostate.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/22/2021/06/CameronPeakFirePODsReport.pdf

[2] https://www.regulations.gov/comment/USDA-2021-0003-1246

[3] https://www.forestsandrangelands.gov/strategy/

[4] https://www.regulations.gov/comment/USDA-2021-0003-0949

[5] https://www.regulations.gov/comment/USDA-2021-0003-1303