If only…as much research went into “changing public behavior with different education/enforcement strategies on federal lands” as went into modeling the impacts of future climate change on random plants and animals; or projections to 2200 of burned acres and severity. Oh well… This also reminds me of our discussion of historic conditions and how they should inform future management. In this case, “it worked then, will it work today and tomorrow, or will something work better?

The topic came up as part of an Rural Voices for Conservation Coalition 2020 Recreation Season After Action Review .

The Forest Service should invest in increased staff or volunteer capacity at recreation sites. Having dedicated hosts at recreational sites, whether through agency staffing or partnerships with local NGOs (e.g Wallowa Resources’ Community Solutions, Inc. manages USFS campgrounds in Eastern Oregon) has been critical to ensuring that visitors are educated on responsible recreation practices and that COVID-19 protocols and policies are enforced.

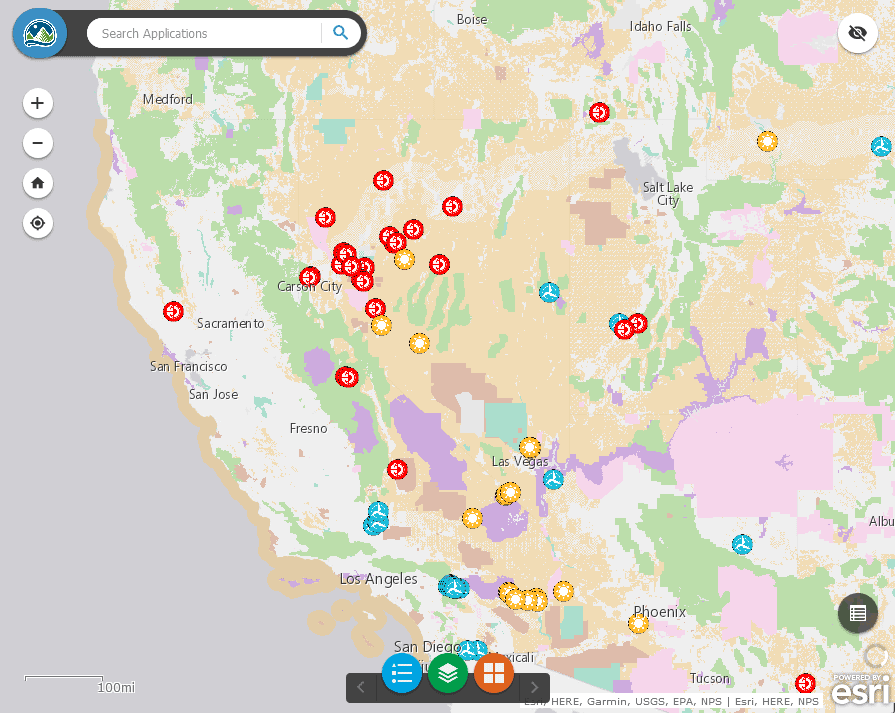

It came up in the Flathead Forest Plan litigation discussion due to the impacts on grizzly bears of illegal entry on roads. It comes up in Bears Ears discussions, as if Monument designation would stop people from pot-hunting, defacing pictographs and other bad things. It’s a common problem across the Forest Service and BLM, where acres are large and numbers of employees are small.

Les Joslin wrote a piece about the value of what “fire prevention guards” used to do:

Climate change has increased wildfire hazard by making fuels dryer for longer periods of time. The key to effective wildfire prevention is reaching the primary risk factor—visitors to and other users of the national forest and adjacent wildland-urban interface lands—with an effective fire prevention message. This is best done through person-to-person communication of a wildfire prevention message by a friendly fire prevention officer. Bend and other Central Oregon fire departments and districts should team up with the Deschutes National Forest to field and fund such fire prevention messengers—modern descendants of the fire prevention guard I once was.

“I don’t know that any fire prevention guard ever prevented a fire just by riding around in his truck,” I wrote in that memoir. “I know I didn’t, because I didn’t. The key to these fire prevention patrols was public contact, and the key to public contact was to get out of the patrol truck and talk with people. So, instead of just driving through campgrounds and raising dust, I routinely parked and walked the campgrounds. That made me available to visitors, either to initiate conversations or to respond to their questions. Outside developed campgrounds, I parked a respectful distance from and walked into camps to greet the campers, answer whatever questions they had, and work my fire prevention message…into the conversation. I did the same along heavily-fished streams.”

“Availability’s partner…is visibility, and I made it a point to look the part, to be easily recognized as a Forest Service representative. A good haircut and a clean shave, a freshly pressed uniform shirt with badge in place, clean green jeans and solid work boots, coupled with a pleasant disposition, projected a positive image. There is no place in public service, I agreed with the district ranger and the fire control officer, for slovenly appearance and bad manners. … I’m convinced this friendly, helpful, face-to-face approach contributed to my success on the job” and to prevention of destructive wildfires. Central Oregon fire prevention officers—on the ground in Forest Service green or fire department or district blue—could replicate such success.

“Fire prevention is a funny business,” I wrote. “You never really know how good you are at it because you never really know if you’ve actually prevented a wildfire. There’s no objective measure of success. Failure is much easier to prove.” But, as the old saying goes, “an ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure.” Strengthening the region’s Project Wildfire efforts toward wildfire preparedness and mitigation measures that address the hazards by beefing up the wildfire prevention effort that addresses the risks—vastly increased with explosive population and visitation growth—would be well worth the minimal additional cost.

At the time, it was considered worth the money to have “boots on the ground”; even though federal employees are expensive, and yet, as Les points out, just the fire prevention aspect could have economic benefits. But presence in those days was different; today we have all kinds of virtual presence. Are human beings a necessity or a luxury (in terms of being out there)? Partners can certainly help get the message out, but how does that work exactly when volunteers faced with a grumpy and potentially volatile rule-breaker? In what ways can some combination of law enforcement folks, volunteers and technology help educate and enforce rules?

I think “having rules that mean something” and “preventing human ignitions” are both Things We Can Agree On.