I thought this storyin the Denver Post was interesting. It raises a question, though, we don’t really know why populations are declining, but the lawsuit from Western Watershed seems to be about grazing. This is not surprising, since that seems to be something WW doesn’t like. For whatever reason, WW doesn’t seem to have the point of view of many (at least in Colorado and Wyoming) that losing public lands ranchers also means losing the home ranch, and the home ranch then tends to become housing developments. And residential development is another threat to the sage grouse.

Grazing as a direct cause of the recent decline seems unlikely Grazers have been grazing maybe since the 1870’s and we can imagine that practices have improved through time. So apparently grazing and GSG have coexisted for the last 150 years. Here’s a story in the Crested Butte Journal about ranching in the valley. So why stop that if it’s not the cause?

If other things (known and unknown) are responsible for the decline (we are talking since the 70’s) why target grazing in the lawsuit? Will it actually help the bird? We don’t know, since we don’t know why it’s declining. For a while, as you can see, since 2005, the collaborative groups and ranchers seem to have made an impact.

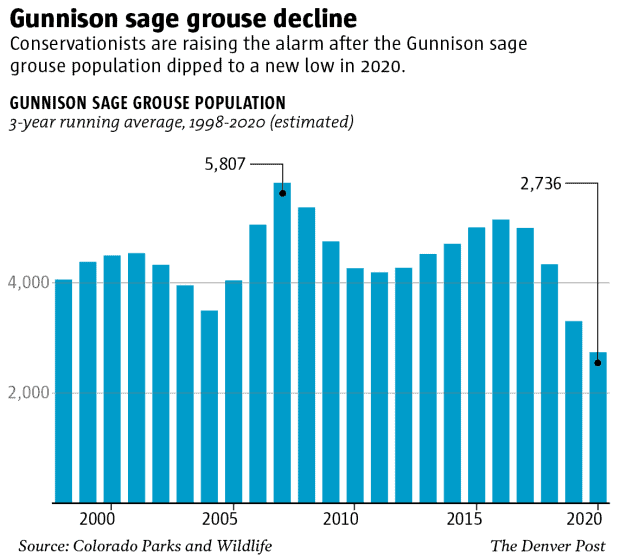

CPW provides these population estimates:

In the years after it was named a new species, millions of dollars were spent on conservation efforts. Gunnison County hired a sage-grouse coordinator in 2005. The federal government paid for aerial seeding to provide food for the grouse and changed their mowing practices to cater to the bird. In 2014, the species was listed as threatened under the Endangered Species Act.

The Gunnison sage grouse numbers increased between 2004 and 2007, and annual counts of the males at the breeding grounds have shown the total population hovering between about 4,000 and 5,000 since then — until 2018, when the numbers began to plunge.

The total population was estimated at 3,500 in 2018, 2,100 in 2019 and 2,500 this year, according to data provided by Colorado Parks and Wildlife.

It could be part of a cyclical decline, a temporary dip driven by drought and two tough winters, but with so few birds left and with their habitat continually shrinking, the drop has raised alarm bells for conservationists, and for Braun.

Still, efforts are underway to protect the birds, said Jessica Young, who pushed Braun to recognize the birds as a separate species when they worked together beginning in the 80s.

“Since I live in Gunnison and make my life in Gunnison, I see day in and day out how hard people are working on the issue,” she said. “What he sees from the outside is the numbers, and the decline and the small populations literally starting to wink out. So we see two different worlds. I’m deeply concerned about them. I absolutely consider them imperiled….but I might have a bit more hope because of how hard I’ve seen people try.”

It’s interesting how Jessica Young talks about “different worlds”; it’s something I’ve heard quite a bit with these kinds of controversies. We’ll be discussing this more when we get to The Battle for Yellowstone.

In early December, the Center for Biological Diversity and Western Watersheds Project filed a lawsuit against the Bureau of Land Management, U.S. Forest Service, National Park Service and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, alleging that the federal agencies have failed to do enough to protect the Gunnison sage grouse.

The lawsuit, one of many over the years, takes aim at the amount of grazing that is allowed on publicly owned sage grouse habitat, arguing that the grazing is harming the birds by destroying vegetation they rely on, limiting their ability to breed and hide from predators.

“Ultimately the bird is critically imperiled and something has to change,” said Talasi Brooks, staff attorney at Western Watersheds. “Maybe it’s taking cows off the land, maybe it is changing the season of use…but one way or another, any movement toward actually doing something about the threat of livestock grazing to the sage grouse would be a good thing.”

It sounds like ranchers and the BLM and other cooperators, have, indeed, been assiduously doing things.. and they seemed to be working, but took a sudden downturn associated with heavy snow years. It seems to me that it’s another case where we don’t really know why populations are declining, but litigators round up the usual suspects that they don’t want around. Using lawsuits as a policy tool in this case can 1) place the pain on certain groups that the litigatory groups don’t approve of, and 2) placing the power to place that pain outside the hands of local people (justice question), and 3) having policy with impacts on folks’ livelihoods determined in settlements behind closed doors, without knowledgeable on the ground people, nor the public involved (both a justice and “are you getting the best information to decide” question).

It can effectively cut local people and their knowledge out of the decision-making process, which has serious justice implications IMHO. It can also simply not work for the species, as the target groups may not be the cause of the problem, and these changes could possibly make things worse for the bird.