Since it’s been over three weeks since I’ve seen a Forest Service summary, here’s some news that’s getting old.

FOREST SERVICE CASES

The Center for Biological Diversity filed a Notice of Intent to Sue the Forest Service and U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service to block the Lee Canyon ski resort expansion on the Humboldt-Toiyabe National Forest that would affect the federally endangered Mt. Charleston blue butterfly. This would be the second lawsuit, following new consultation on the project after the first lawsuit (discussed here).

The government has appealed the district court’s adverse decision on this landscape-scale, condition-based “project” on the Tongass National Forest to the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals. (Southeast Alaska Council v. Forest Service, discussed here most recently.)

On August 27, the Center for Biological Diversity sued the Forest Service over violations by grazing permit holders for the Sacramento and Aqua Chiquita allotments in the Lincoln National Forest. The Forest Service has documented that the permit holders have improperly allowed their cows to enter protected streamside meadows, habitat for the federally endangered New Mexico meadow jumping mouse. (A similar case is pending involving the Apache-Sitgreaves National Forest, summarized here.)

On August 28, the Bitterroot National Forest withdrew its decision on the Gold Butterfly vegetation management project, conceding that it used a different definition of old growth than was in its forest plan, and that it did not comply with road density requirements in the forest plan for elk. (Friends of the Bitterroot v. Anderson, summarized here. This article includes a map.)

On August 25, the district court for the District of Idaho upheld the decision by the Caribou-Targhee National Forest regarding the Rowley Canyon Wildlife Enhancement Project, which authorizes the thinning of juniper trees and prescribed burning to “eliminate the threat of future catastrophic fire” (in the court’s words) within the Elkhorn Mountain Inventoried Roadless Area. (Wildlands Defense v. Bolling, summarized previously here, including plaintiff’s perspective).

Note: This was a case involving the categorical exclusion for “timber stand and/or wildlife habitat improvement activities” and alleged “extraordinary circumstances.” I thought the court took a rather extreme position on the criteria for deference to the agency; I have never understood that ANY analysis would be sufficient to comply with NEPA (my emphases).

Plaintiffs take issue with the depth and scope of the Forest Service’s analyses, claiming that neither was adequate to support the Forest Service’s finding that the proposed project will not lead to any significant impacts or extraordinary circumstances. But that is not the same as saying the Forest Service failed to conduct any analysis whatsoever. Within the administrative record, there are extensive analyses of the Project’s effects upon all users, including animals and avian species who depend upon the habitat proposed to be treated. The Court must defer to the agency on matters within the agency’s expertise unless the agency completely failed to address a factor that was essential to making an informed decision.

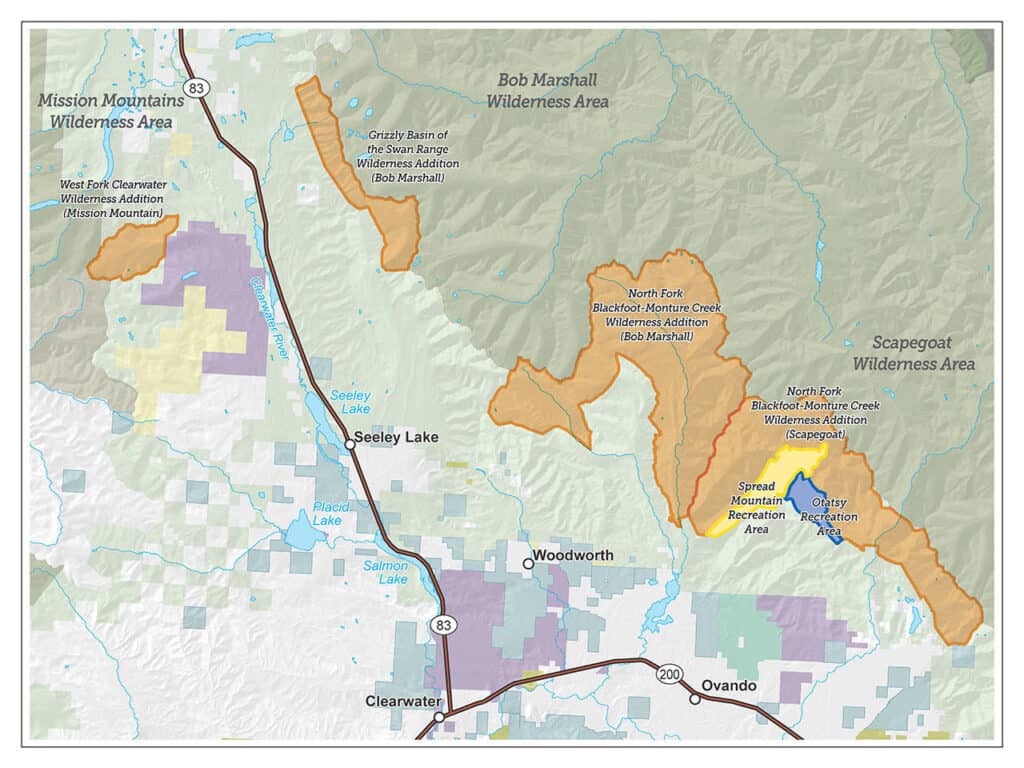

After receiving a Notice of Intent to Sue over its effects on grizzly bears, the Lolo National Forest has delayed implementing its decision on the Soldier-Butler forest management project in order to reinitiate consultation with the Fish and Wildlife Service. The project would involve building new roads in an area recently designated in the forest plan as a Demographic Connectivity Area for grizzly bears.

OTHER CASES

On June 26, 2020 the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals, on a 2-1 vote, held that the Administration illegally transferred Department of Defense funds for the purpose of building a border wall on the Mexican border. (Sierra Club v. Trump. A related lawsuit was discussed here.)

A coalition of environmental groups sued the Interior Department Aug. 24 urging a federal judge to halt implementation of the BLM’s plan to expand oil and gas opportunities in Northwest Alaska, challenging the EIS prepared by the BLM.

After litigation for delaying a decision (discussed here), the U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service has listed the Humboldt marten of southern Oregon and northern California as threatened under the Endangered Species Act. However, apparently using new provisions enacted by the Trump Administration, the listing includes “an array of broad and vague exemptions for forest management activities.”