While we (maybe) await further news of what the Forest Service thinks is news, here’s some of what I’ve seen. Some others we’ve looked at already:

North Cascades grizzly bears (see comments)

FOREST SERVICE

In a case that has been discussed here a number of times (such as here) The Montana federal district court found that the Forest Service had acted in “bad faith” on the Ten Mile-South Helena project on the Helena-Lewis and Clark National Forest, finding that it would require reconstruction of old roads in an area protected by the Roadless Area Conservation Rule. The judge refused to defer to the agency:

“The matter is not one that involves specialized or expert knowledge,” Christensen wrote. “The problem is basic geometry. A vehicle with a wheelbase 9 to 11 feet wide requires a road similarly wide. The Lazyman area does not contain a network of preexisting roads 9 to 11 feet wide. Therefore, bringing this equipment into the area will require the Forest Service to widen the roads.”

The judge also held that the project would require additional NEPA analysis after changing it to allow mechanized logging equipment, and the Forest would need to consult with U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service on the impacts to grizzly bears of proposed trails that would allow mountain bikes. Plaintiffs’ takes on the opinion are here and here.

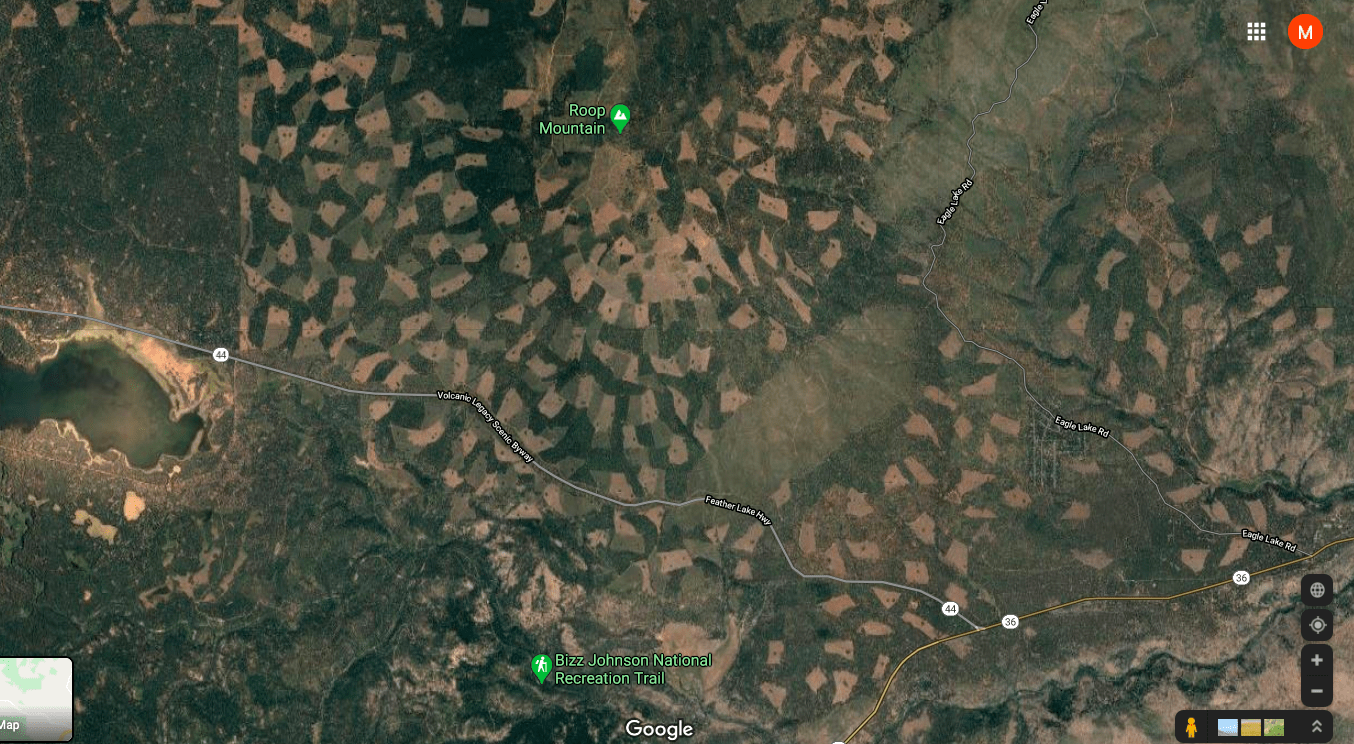

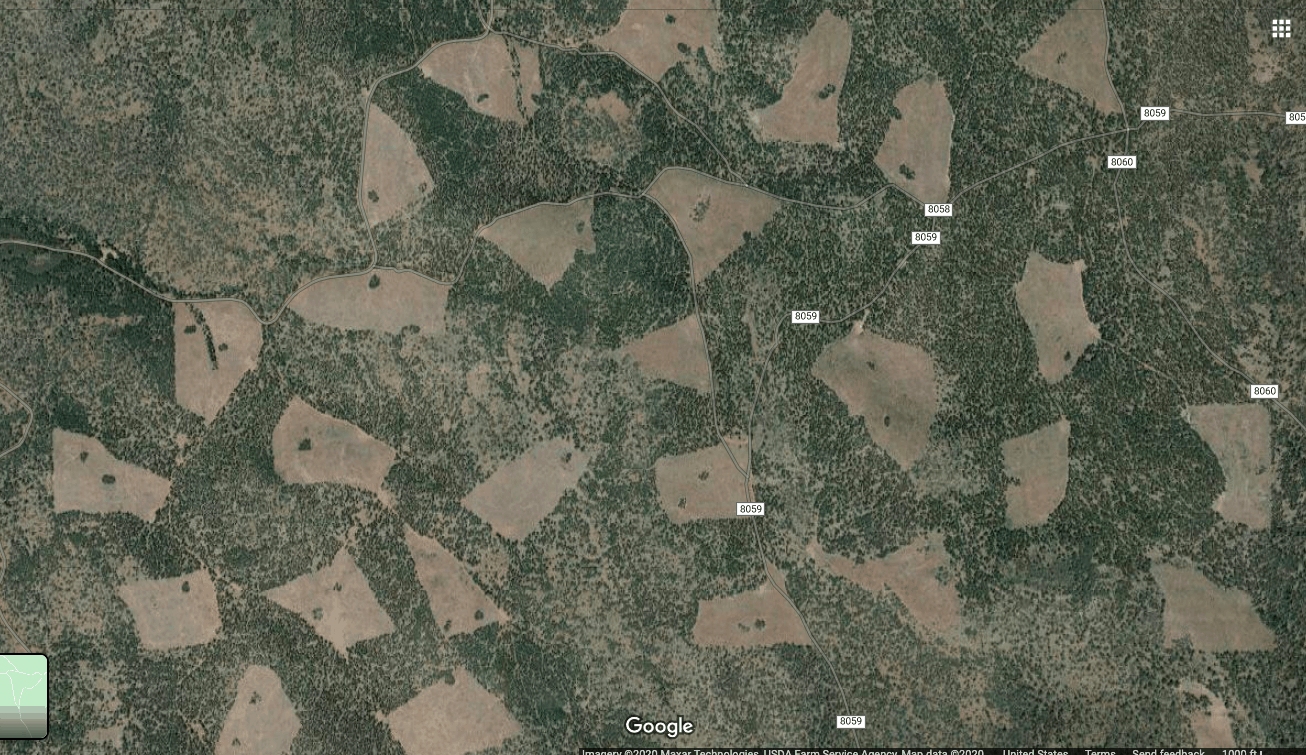

The first week of July, the Friends of the Clearwater and the Alliance for the Wild Rockies filed a lawsuit against the Lolo Insect and Disease Project on the Nez Perce-Clearwater National Forest, which calls for logging across 3,380 acres in 30 harvest units. The Plaintiffs’ perspective, focusing on the threatened Snake River Basin steelhead, is here (the National Marine Fisheries Service is a co-defendant).

Remember that pipeline that the Supreme Court just said could be built on national forest lands and under the Appalachian Trail (in Cowpasture River Preservation Association v. U. S. Forest Service)? On July 5, developers of the Atlantic Coast natural gas pipeline announced they are canceling the project, blaming legal setbacks and economic uncertainty.

OTHER AGENCIES

On June 29, the Center for Biological Diversity and Healthy Gulf filed a notice of intent to sue the U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service for failing to develop recovery plans for the endangered reticulated and frosted flatwoods salamanders. (The lack of a recovery plan for the latter was an issue during the Francis Marion National Forest’s forest plan revision, and arguably influenced its ability to contribute to recovery.)

On July 1, WildEarth Guardians and Wilderness Workshop sued the U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service over its failure to take any action in response to a 2016 court order striking down the agency’s exclusion of Canada lynx habitat in the species’ entire southern Rocky Mountain range from designation as critical habitat.

The U.S. Supreme Court ruled on July 9 in McGirt v. Oklahoma that much of Oklahoma’s tribal lands had never been rescinded, and that the state had no criminal jurisdiction over those lands. However, some Indian law experts believe the ruling may lead to more civil and regulatory oversight by tribal governments on land within historic reservation boundaries. This article cites an example of Mt. Graham, now part of the Coronado National Forest.

On July 14, conservation and landowner groups filed a new lawsuit challenging the Trump administration’s approval of the Keystone XL tar-sands pipeline to be constructed on federal BLM lands in Montana. The complaint asserts that the reviews by the BLM and the Fish and Wildlife Service under the National Environmental Policy Act and Endangered Species Act are riddled with the same errors and omissions as earlier versions deemed insufficient by a federal court in 2018.