PR from Sen. Ron Wyden of Oregon. Dunno if this bill has a shot, but he carries some weight on Capitol Hill. Ranking Finance Committee member, long-time member of the Energy and Natural Resources Committee.

May 11, 2020

Wyden Introduces Bill to Make Major Investments in Public Health, Wildfire Prevention and Rural Jobs as Part of COVID-19 Economic Stimulus Efforts

New Wyden legislation would provide significant investment for wildfire resiliency to protect Americans from wildfire smoke, boost support for rural economies hit hard by COVID-19

Washington, D.C. – U.S. Senator Ron Wyden, D-Ore., today introduced legislation that would bolster wildfire prevention and preparedness to protect the health and safety of communities during the unparalleled combination of threats posed by wildfire season and the COVID-19 pandemic.

The legislation also would provide relief and job creation measures that equip rural economies to respond to the unique threats they’re facing during this public health and economic crisis.

“A historic global pandemic that’s still raging at the start of wildfire season adds up to a prescription for major problems in the months ahead to public health and rural jobs in Oregon and nationwide,” Wyden said. “This legislation takes that pair of problems head-on with a comprehensive attack that connects all the dots with a 21st century Conservation Corps and more to protect health and save jobs.”

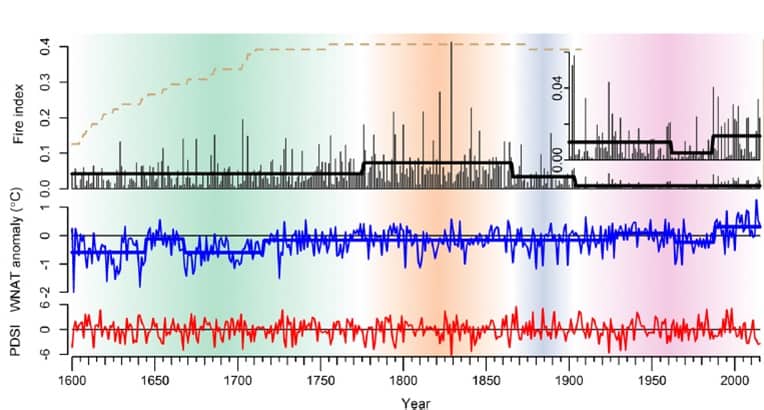

The impacts of COVID-19 on public health and the economy, combined with high levels of drought throughout the West, create unprecedented wildland firefighting challenges in 2020. Those at increased risk for adverse health effects due to wildfire smoke exposure – people who suffer from heart or respiratory diseases – are also particularly vulnerable to COVID-19. The crisis also quickly brought the outdoor economy to a halt. Many forest workers, despite their essential work, were laid off and others, like outfitters and guides who rely on tourism and outdoor recreation, are unable to work during their busy season.

Wyden’s 21st Century Conservation Corps for Our Health and Our Jobs Act will provide significant investment in wildfire prevention and resiliency efforts; programs that can get rural Americans back to work when it’s deemed safe by public health experts to do so; direct relief for outfitters and guides; as well as extensive resources for watershed restoration. The legislation:

- Provides an additional $3.5 billion for the U.S. Forest Service and $2 billion for the U.S. Bureau of Land Management to increase the pace and scale of hazardous fuels reduction and thinning efforts, prioritizing projects that are shovel-ready and environmentally-reviewed;

- Establishes a $7 billion relief fund to help outfitters and guides who hold U.S. Forest Service and U.S. Department of the Interior special use permits – and their employees – stay afloat through the truncated recreation season;

- Establishes a $9 billion fund for qualified land and conservation corps to increase job training and hiring specifically for jobs in the woods, helping to restore public lands and watersheds, while providing important public health related jobs in this time of need;

- Provides an additional $150 million for the Collaborative Forest Landscape Restoration Program, the flagship program for community forest restoration and fire risk reduction;

- Provides $6 billion for U.S. Forest Service capital improvements and maintenance to put people to work reducing the maintenance backlog on National Forest System lands, including reforestation;

- Provides $500 million for the Forest Service State and Private Forestry program, which will be divided between programs to help facilitate landscape restoration projects on state, private and federal lands, including $100 million for the Firewise program to help local governments plan for and reduce wildfire risks;

- Provides $10 billion for on-farm water conservation and habitat improvement projects;

- Provides full and permanent funding for the Land and Water Conservation Fund, which has broad bipartisan support; and

- Provides $100 million for land management agencies to purchase and provide personal protective equipment (PPE) to their employees, contractors and service workers.

A one-page summary is available here.

A section-by-section summary is available here.

A copy of the legislative text is available here.